Rules Lacking for Geoengineering Projects for Global Warming

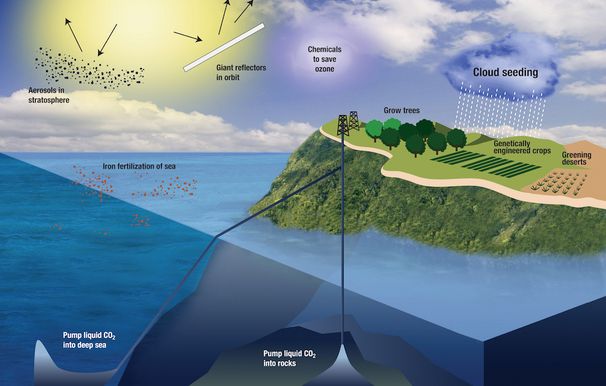

What if someone wanted to deploy a massive project to try to reverse climate change today? Perhaps some researchers wanted to spray sulfur particles into the stratosphere to reflect away some of the sun's energy, cooling the Earth in an attempt to compensate for global warming. Or perhaps a group wanted to unload some fertilizer into the ocean, so more algae will grow and absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Their actions may have global consequences, but would such projects have to answer to a global governing body?

Such geoengineering projects — Earth-altering plans to combat global warming — sound pretty futuristic. Indeed, it would be decades before such projects are likely to be deployed, if they ever are, say scientists InnovationNewsDaily contacted. Yet a little bit of the future is already here, as researchers have just started to propose outdoor experiments for technologies that would apply to geoengineering projects. Previously, researchers studied the effects of geoengineering in labs or using computer programs, but now a few groups want to try experiments outside of the lab. Harvard University researchers David Keith and James Anderson recently grabbed headlines for a proposal to put small amounts of sulfur particles into the air, to study how such particles interact with the atmosphere.

At InnovationNewsDaily, we wondered what exactly would happen if an individual or nation wanted to deploy a project, or preliminary tests for a project, that could potentially alter the climate for everybody on Earth. [Changing Earth: 7 Ideas to Geoengineer Our Planet]

Little international regulation

For now, at least, there aren't any international laws that apply to geoengineering projects generally. "There would really be no place to go to actually challenge" a geoengineering project, said Dan Bodansky, an Arizona State University law professor who specializes in climate change.

The United Nations' Convention on Biological Diversity forbids any projects that would affect biodiversity until scientists further study the consequences. Small-scale scientific experiments are allowed. However, the convention "has neither the mandate nor sufficient political clout to broker a geopolitical agreement," Jason Blackstock, a scholar of science and society at the University of Oxford, wrote in a column in the journal Nature in June.

The London Convention and Protocol, an international treaty regarding the dumping of pollutants in the ocean, may apply to ocean fertilization projects and to any plans to capture carbon from the atmosphere and bury it in the ocean floor. Under these rules, individual countries would issue permits for projects. If other countries objected, they would have to lodge a complaint that the permit-issuing country wasn't holding up its treaty obligations. "In other words, the challenge would be somewhat indirect," Bodansky told InnovationNewsDaily.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The way laws are currently structured, challengers to geoengineering projects would probably turn to the national laws of the hosting country. "It would depend, I think, really primarily on national law," Bodansky said. In the U.S., for example, the Clean Air Act is likely to govern any sulfate-spewing activities. But there's no overall, international court that would review a geoengineering project that got proposed today.

Open to international protests

Yet people and groups may still alter the course of scientific experiments, even if the tests are expected to have little impact on the environment. Last fall, U.K. researchers proposed to use a balloon to hoist a hose 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) into the air. The hose would spray water, testing the feasibility of using a similar hose in the future to spray sulfur particles to shield the Earth.

Sixty environmental organizations signed a petition to stop the project, which is called the Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering project, or SPICE. The leading protestor, the Canadian-based ETC Group, knew SPICE wouldn't affect the environment, said an ETC project manager, Kathy Jo Wetter. The ETC Group opposes geoengineering altogether, believing that the risks outweigh the benefits and that the technologies distract from the important work of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. "We think geoengineering is a dead end and should not go forward," Wetter said.

Responsibility lies with researchers

After the protest, SPICE's lead scientist, Matthew Watson of the University of Bristol, decided to put the experiment on hold. He acknowledged there was no agreed-upon way to review projects like his and to listen to other stakeholders, he wrote in an email statement to Nature. "People who are involved in this kind of research right now have to take extraordinary responsibility for doing the right thing," said Jane Long, associate director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California and a co-chair of a bipartisan report on geoengineering for U.S. lawmakers. Long called Watson "an exemplary character" for his decision.

Is there danger of an individual, lab or country choosing to go ahead with geoengineering projects or tests on its own? Although researchers don't have precise estimates regarding the costs of geoengineering projects, some think adding sulfur particles to the atmosphere could happen on "the sort of budget an extremely wealthy individual might have," said Steve Rayner, director of the University of Oxford's science and society institute.

Yet Rayner and Long said they think it's unlikely an individual or country would try to mount project or test on its own in the face of international protests. On the other hand, Wetter said the possibility of a country deciding to geoengineer on its own "is a big concern."

Uncertain future

What Rayner, Long and Wetter all agree on is the need for international regulations and cooperation. "You're talking about an action that's going to have transborder consequences, hopefully global consequences, if it works," Rayner said.

Groups such as ETC hope for an international ban on geoengineering, while Long and Rayner seek a way to review projects. Considering the difficulty countries have had in signing emissions treaties, however, it may be a long road to a worldwide agreement on geoengineering, Rayner and Long said.

A few conferences have worked on guidelines for geoengineering, such as a U.K. Royal Society-led report, an "Asilomar" meeting styled after a 1975 conference about DNA engineering, and the U.S. report Long led. None have come up with binding resolutions regarding geoengineering.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to Live Science. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily staff writer Francie Diep on Twitter @franciediep. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.