With NASA's Curiosity rover safely on the ground inside Mars' huge Gale Crater, scientists are getting more and more excited about what the six-wheeled robot may discover.

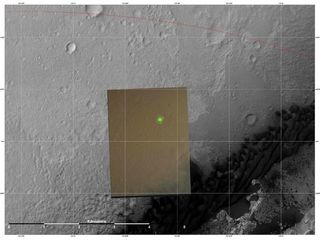

Gale Crater, where Curiosity touched down Sunday night (Aug. 5 PDT), is a unique and intriguing place where Curiosity could make serious scientific hay over the next several years, researchers and NASA officials say.

"We are going to have the opportunity for untold discoveries," Doug McCuistion, director of NASA's Mars Exploration Program, said on Sunday before Curiosity landed. "This location, Gale Crater, is absolutely amazing."

A mountain inside a crater

Gale Crater, which was announced as Curiosity's destination in July 2011, sits a few degrees south of the Martian equator. While the crater is 96 miles wide (154 kilometers), Gale's size is not its most eye-catching feature. That would be Mount Sharp, the giant mountain rising from Gale's center. [Gallery: Gale Crater, Curiosity's Landing Site]

At 3 miles high (5 km), Mount Sharp is taller than any peak in the continental United States. Scientists think it's the remnant of a much larger block that once filled Gale Crater, though they're not sure exactly how the mound formed.

"In one go, you have flat-lying strata that are 5 kilometers thick," Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, a geologist at Caltech in Pasadena, told SPACE.com last month. "There's nothing like that on Earth."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

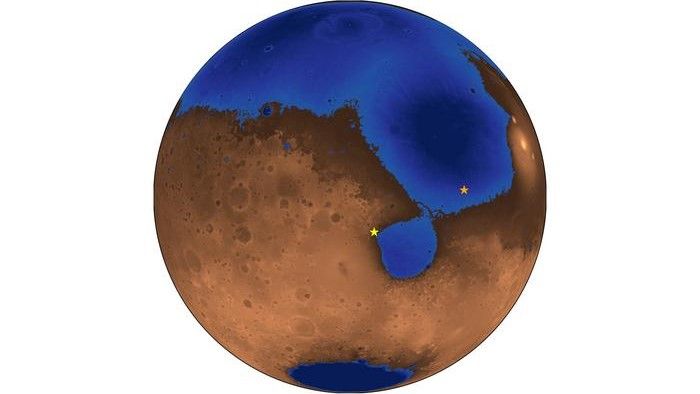

Those strata preserve a record of Mars history spanning perhaps a billion years or more, researchers say. Mars-orbiting spacecraft have spotted evidence of clays and sulfates in Mount Sharp's lower reaches, suggesting that the mountain's base was exposed to liquid water long ago.

On Earth, life tends to thrive wherever liquid water exists. So Curiosity — whose main goal is to determine whether Mars was ever capable of supporting microbial life — will probably spend lots of time poking around Mount Sharp's flanks and foothills.

But Grotzinger and his team also hope to send the $2.5 billion rover higher up the mountain's gentle slopes. About 2,300 feet (700 meters) up, Curiosity would cross a threshold, leaving the hydrated minerals behind and encountering layers that speak of much drier times.

"Something happened on Mars, and it went dry, and that's what we have today," Grotzinger said. "The question is, what was that event? What was that trigger? What happened environmentally? My hope is that we'll get some insight into this Great Desiccation Event."

Lingering near the landing site

Curiosity's team has just begun the months-long series of checkouts that will assure the rover and its 10 science instruments are in good working condition on the Martian surface. But even when the robot is ready to roam, scientists probably won't send it straight to Mount Sharp.

That's because the spot where it touched down is interesting, too. Curiosity hit the red dirt just downslope from an ancient alluvial fan, a feature likely created by water flowing downhill. Data gathered by orbiting spacecraft also suggest that many deposits surrounding the rover may have formed in the presence of water.

Mission scientists are therefore keen to give the area a serious going-over.

"We're really excited about this, and it suggests to us right away that we've got some cool geology to do ahead of us," Grotzinger said.

Curiosity's prime mission is slated to last roughly two Earth years, but the nuclear-powered rover could keep exploring far longer than that if key parts don't break down, the robot's handlers have said. Longevity is key, because it may take a while to unlock the mysteries hidden away in Gale Crater, and in the many layers of Mount Sharp.

"We have chosen the most spectacular field site," Grotzinger said. "It just continues to give."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Visit SPACE.com for complete coverage of NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. Follow senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.