Fossils of New Shark Species Found in Arizona

The remains of several new toothy shark species, with at least three dating to 270 million years ago, have been unearthed in Arizona, according to a new study.

The research, published in the latest issue of Historical Biology, suggests that Arizona was home to the most diverse collection of sharks in the world during the pre-dinosaur Middle Permian era. The researchers have discovered many other new shark species from the area, with papers in the works to document them.

For now, lead author John-Paul Hodnett described the three mentioned in the latest study:

Nanoskalme natans ("swimming dwarf blade") was a small (about 3.2-foot- long) shark with blade-like cutting teeth. It was probably a scavenger and predator on small fish.

Neosaivodus flagstaffensis ("new Saivodus from Flagstaff") was a medium-sized shark (about 6.6 feet) with gripping teeth that might have been a specialist on nautiloids as a juvenile, but a more generalist feeder as an adult.

Kaibabvenator swiftae ("Swift's Kaibab hunter") was a large (around 19.7 feet ) shark with big serrated cutting teeth. It was presumably an active apex predator on large prey including other sharks, similar to the modern great white shark.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hodnett, a researcher in the Museum of Northern Arizona's Geology and Paleontology Department, analyzed the shark remains with colleagues David Elliott, Tom Olson and James Wittke. The sharks were unearthed at what is known as the Kaibab Formation of northern Arizona.

WATCH VIDEO: What Would Happen If Sharks Disappeared?

Elliott told Discovery News that a shallow, warm sea covered this part of Arizona at the time. Today, this same area is a high plateau region supporting a Ponderosa Pine forest. Although hard to imagine, the region was once home to a bustling shark-eat-shark ecosystem.

"At this time, sharks were the main vertebrate predators in marine environments world wide, and they were very numerous and diverse, filling niches that were occupied later by bony fish and even mammals, such as cetaceans (a group that includes whales and dolphins)," Hodnett said. "The main predators on sharks would have been other sharks."

SHARK WEEK: Don’t Miss the 25th Anniversary of Shark Week

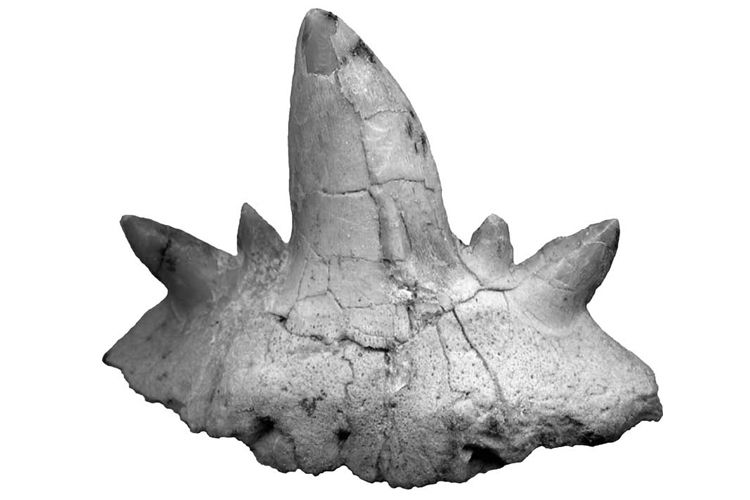

According to the researchers, the new species are all ctenacanthiformes, an extinct order of primitive sharks characterized by two ornamental dorsal fin spines, and teeth in which the central cusp is large and well-developed, with smaller lateral cusps. The sharks' tails were symmetrical, unlike the asymmetrical tails of most modern sharks, and their heads were short-snouted.

The findings reveal how rich and diverse marine life was at the time, some 45 million years before the first dinosaurs even appeared.

Elliott shared that on land during this period, "the most important vertebrates were the synapsids (pre-mammals) that included animals such as Dimetrodon." That was a lizard-like beast with a large sail on its back.

Sharks, however, clearly ruled Arizona back in the day.

John Maisey, curator and research chair of the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, told Discovery News, "The real significance of the paper is in revealing the considerable diversity shown by these top predators shortly before their disappearance at the end of the Permian. The Permian marks a real transition in the shark world, from 'ancient' to 'modern,' and the modern diversity of sharks and rays only begins in the early Jurassic."

Maisey continued, "It is still not clear whether some sharks, classified as 'ctenacanths,' actually gave rise to modern shark-like fishes, or represent a dead-end group; that is something which may emerge as research continues. This study is an important step in the process."

This story was provided by Discovery News.