It looks like there will be no shortcuts to peer beneath the surface of Mars for NASA's Curiosity rover.

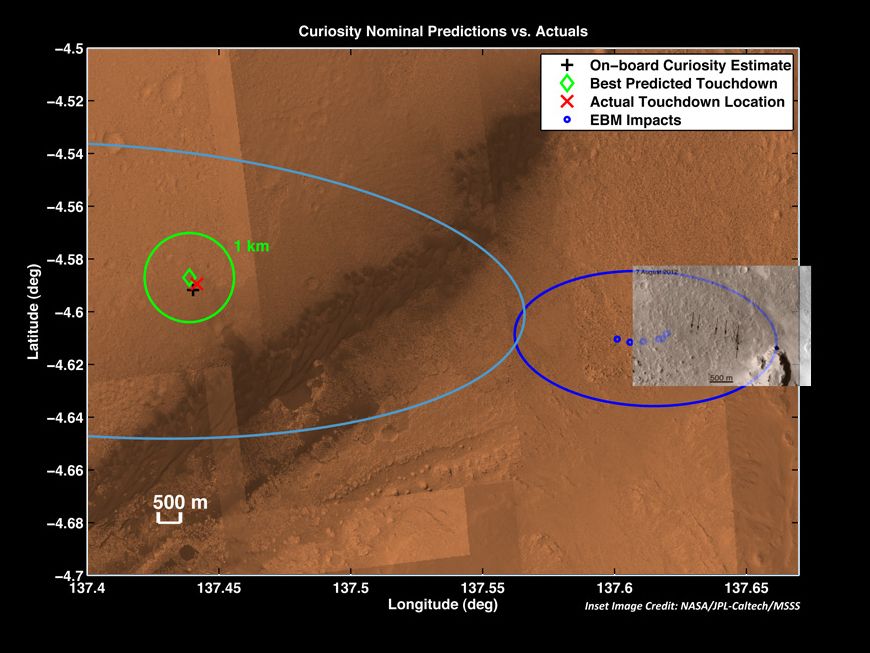

Mission scientists had held out some hope that the 1-ton rover might be able to explore fresh impact craters produced by ballast ejected during the Curiosity rover's landing Sunday night (Aug. 5). But new images from a NASA Mars orbiter suggest that reaching those craters may be too tough, since a treacherous stretch of sand dunes lies in the way, researchers said.

"We would have to do an enormous U-turn around the dune field, and I just don't think it's going to be practical to do that," Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, of Caltech in Pasadena, told reporters Wednesday (Aug. 8).

Seeing inside Mars

Curiosity is the heart of NASA's $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory mission (MSL), which seeks to determine if the Red Planet has ever been capable of supporting microbial life. In their search for habitable environments, MSL scientists are naturally keen to investigate the Martian subsurface wherever possible.

The Martian surface gets blasted by radiation much more severely than Earth, because the Red Planet lacks a protective magnetic field and has a relatively thin atmosphere. As a result, many researchers think that Martian life — if any exists today — would more likely be found underground. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

Curiosity mission scientists hoped that the rover's daring "seven minutes of terror" plunge through the Red Planet's atmosphere Sunday might give them a chance to glimpse the Martian subsurface. Shortly before the MSL spacecraft deployed its supersonic parachute, it ejected six 55-pound (25-kilogram) tungsten slugs to help improve balance.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I think a lot of us hoped that those things would come down really close to where we landed, because as tungsten, it's fairly inert, and it makes a fresh impact crater that you could look in," Grotzinger said. "So there'd be a lot of desire to do that."

But new photos from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) suggest that it wasn't meant to be.

Spotting the craters

These photos show that the ballast came down about 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) from Curiosity's landing site inside Gale Crater, MSL researchers announced Wednesday. That's not exactly close, but the possibility of bogging Curiosity down en route is a bigger issue, Grotzinger said.

"Our obstacle is this dune field that we have no desire to drive across unless we have to," he said.

While there may be a little disappointment that the craters appear out of Curiosity's reach, finding them at all is cause for celebration, especially among MSL's entry, descent and landing (EDL) team, researchers said.

"The EDL guys were very excited to see these [photos]," said Mike Malin of Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego, the team leader of MRO's imaging system and principal investigator of several of Curiosity's cameras.

"This is another test of all the modeling they've done for EDL," Malin added. "This tells them how inert objects that aren't doing any activity come through the atmosphere and fall."

Drilling for samples

Curiosity was lowered to the Martian surface on cables by a rocket-powered sky crane, which then flew off to crash-land intentionally a safe distance away. Other MRO photos show that the sky crane landed just 2,100 feet (620 m) or so from Curiosity, but the rover team is not too interested in checking out the crater it made when it came down.

"With all the hydrazine [rocket fuel] that might be present there, we would actually really prefer to avoid that," Grotzinger said on Monday (Aug. 6). "I don't doubt that if our path of science takes us near it, we're really going to try to image it and do everything we can to study it. But otherwise, we try to avoid it."

So if Curiosity wants a fresh subsurface sample, it will likely have to dig for it. The six-wheeled robot can scoop dirt, and a drill at the end of its 7-foot (2.1-m) robotic arm can bore 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) into Martian rock — deeper than any rover has ever been able to go.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.