Mars Surface Made of Shifting Plates Like Earth, Study Suggests

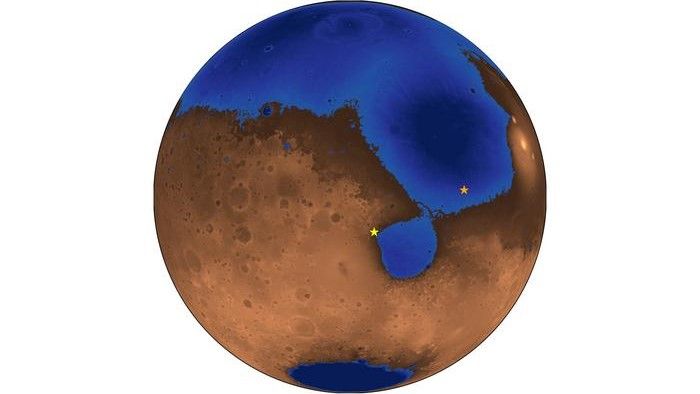

The surface of Mars has been shaped by plate tectonics in the recent past, a new study suggests, making the Red Planet perhaps a better candidate to host life than scientists had thought. Mars may even experience seismic shifts, or 'Marsquakes,' every million years or so.

Scientists have long believed that plate tectonics — in which huge crustal plates pull apart, smash together and dive under one another — exist nowhere in our solar system but Earth. But the phenomenon is also active on Mars, according to the new study.

"Mars is at a primitive stage of plate tectonics," study author An Yin, a planetary geologist at UCLA, said in a statement. "It gives us a glimpse of how the early Earth may have looked and may help us understand how plate tectonics began on Earth."

If Yin is right, life may have had an easier time getting a foothold on the Red Planet than researchers had believed. Plate tectonics could help replenish the nutrients organisms need to survive, bringing carbon and other substances from the Martian interior up to the surface.

Studying satellite views

Yin analyzed about 100 images snapped by NASA's Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft. Of these, a dozen or so held evidence of plate tectonics, he said. [Photos from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter]

"When I studied the satellite images from Mars, many of the features looked very much like fault systems I have seen in the Himalayas and Tibet, and in California as well, including the geomorphology," Yin said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, he saw a steep cliff comparable to cliffs in California's Death Valley, which are generated by a fault. The pictures also showed a very smooth and flat side of a canyon wall — another feature Yin says is strong evidence of tectonic activity.

Further, the Red Planet has several long, straight chains of volcanoes, including three that make up the Tharsis Montes, near the enormous peak Olympus Mons. These linear chains may have formed from the motion of a plate sitting over a "hot spot" in the Martian mantle, as the Hawaiian Islands are thought to have formed on Earth.

"You don't see these features anywhere else on other planets in our solar system other than Earth and Mars," Yin said.

A huge canyon system

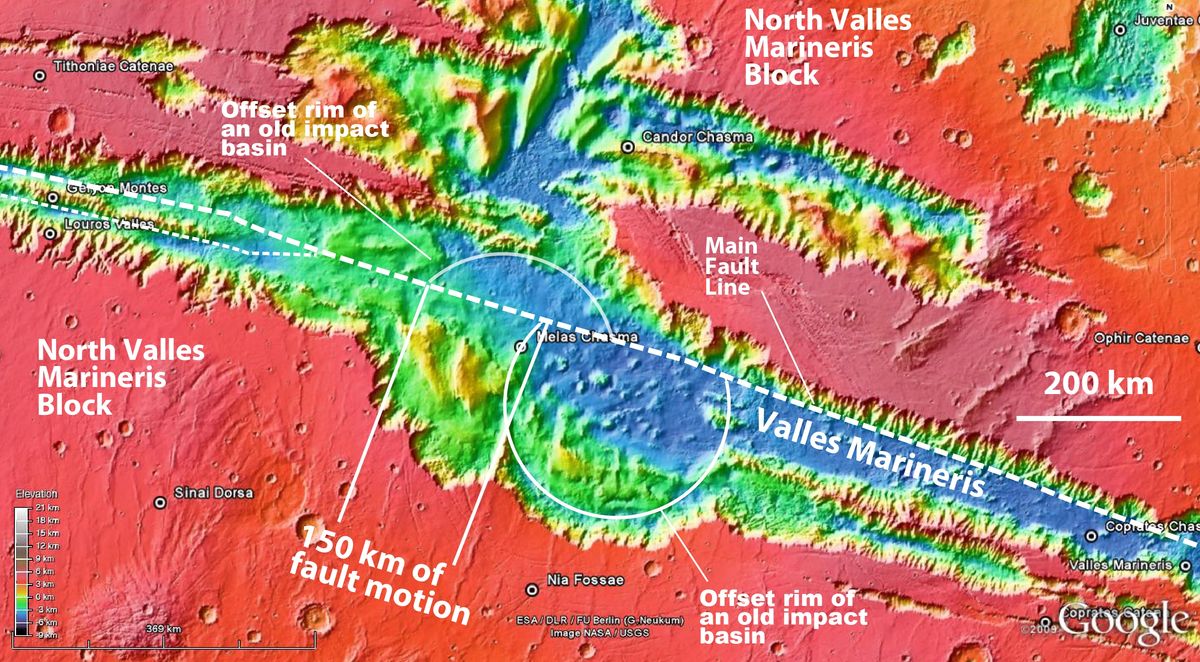

Mars also harbors the longest and deepest canyon system anywhere in the solar system. Valles Marineris extends for nearly 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers), making it about nine times longer than Earth's Grand Canyon.

Scientists have wondered for four decades how Valles Marineris formed. Yin thinks it's yet more evidence for Martian plate tectonics.

"In the beginning, I did not expect plate tectonics, but the more I studied it, the more I realized Mars is so different from what other scientists anticipated," Yin said. "I saw that the idea that it is just a big crack that opened up is incorrect. It is really a plate boundary, with horizontal motion. That is kind of shocking, but the evidence is quite clear."

"The shell is broken and is moving horizontally over a long distance," he added. "It is very similar to the Earth's Dead Sea fault system, which has also opened up and is moving horizontally."

Valles Marineris marks the meeting point of two plates that have moved approximately 93 miles (150 km) horizontally relative to each other, Yin said. He calls these plates Valles Marineris North and Valles Mariners South and thinks they're probably the only plates on Mars. (Earth, by contrast, has seven crustal plates.)

"Earth has a very broken 'egg shell,' so its surface has many plates; Mars' is slightly broken and may be on the way to becoming very broken, except its pace is very slow due to its small size and, thus, less thermal energy to drive it," Yin said. "This may be the reason Mars has fewer plates than on Earth."

Yin thinks the plates are still active today, with the potential to produce "Marsquakes" every now and again.

"I think the fault is probably still active, but not every day," he said. "It wakes up every once in a while, over a very long duration — perhaps every million years or more."

Yin's study was published in the August issue of the journal Lithosphere.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.