Antarctic Moss Lives Off Penguin Poop

Verdant green carpets of moss that emerge during the brief Antarctic summer have an unusual food source, a new study reports: The mosses eat nitrogen from fossilized penguin poop.

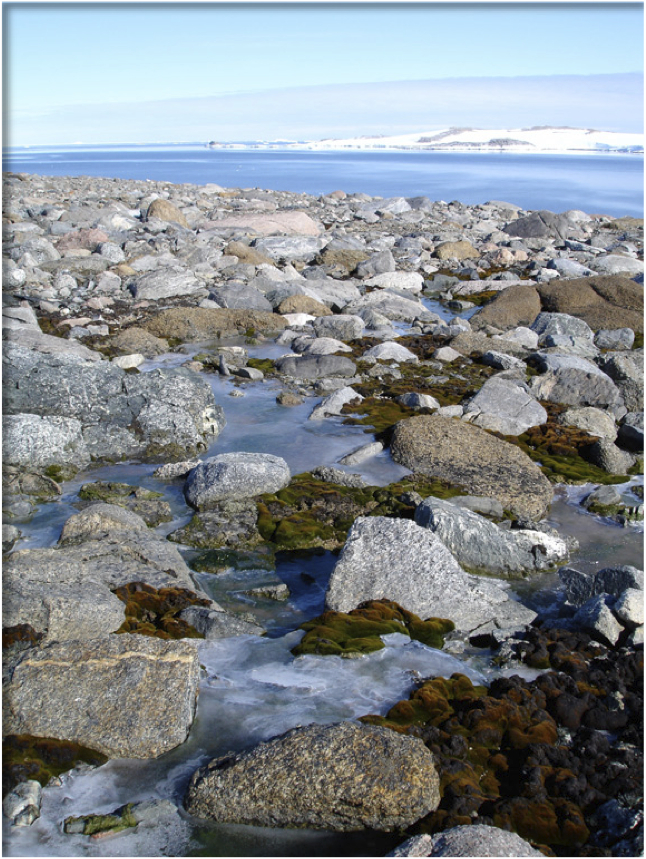

Plant biologist Sharon Robinson, who has studied the mosses for 16 years, sought to find their nutrient source; Antarctic soil generally lacks nourishment for plants. "Most of the soil is very, very poorly developed; it's mostly just gravel," said Robinson, a professor at the University of Wollongong in New South Wales, Australia.

For Robinson, establishing how the moss colonies grow is important because they serve as an indicator of the effects of climate change.

"In East Antarctica, where it is getting drier, our results show moss growth rates have declined over the past 30 years," she told OurAmazingPlanet.

Penguin poop

Chemical analyses were done on the moss to see what isotopes of nitrogen they were eating.Isotopes of different elements contain differing numbers of neutrons in their nuclei. For nitrogen, there are two stable isotopes to look for: nitrogen-14 and heavier nitrogen-15.

Because animals' bodies prefer to excrete the lighter form,heavier nitrogen-15 accumulates with each step on the food chain. In the Antarctic Ocean, krill would have the lowest nitrogen-15 levels, and a top predator, like a penguin, would have the highest.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the analyses, detailed in the September issue of the journal Biodiversity,revealed the mosses had abnormally high concentration of nitrogen-15 isotopes — high enough that the plants seemed to be eating penguins.

"These plants have root signatures that are very, very enriched, indicating the equivalent of the moss eating four orders of things: krill and fish and a penguin and then moss," Robinson said. "They're not actually eating the penguins, but that tells us that they're using guano from seabirds," she said.

The researchers confirmed the nitrogen came from penguin poop because the moss beds grow on abandoned Adéliepenguin colonies. The sites, on the Windmill Islands,are 3,000 to 8,000 years old, and increase in age with distance from the ocean. The colonies are now too high in elevation for nesting (the Earth's crust in Antarctica has been risingsince the end of the last ice age).

Climate links

The mosses only flourish during the summer, in or along lakes and streams formed from meltwater. The plants grow just half a millimeter to two millimeters a year, depending on the species. The best communities are in lakes, where there is a continuous water source, Robinson said.

"They form these big turfs of bright, almost fluorescent green. It is really soft and velvety to touch, and warms with the sun. It's quite a lot warmer than the air," she said.

Nitrogen from the penguin droppings dissolves in the meltwater, and is then absorbed by the moss. When winter returns, the plants go dormant, producing special chemical compounds that allow them to dry out without damage.

When the moss is stressed, it turns red, then brown, then black, before it dries out and dies, and Robinson said she's seen more stressed plants recently. The ozone hole has strengthened surface winds around Antarctica, and faster winds evaporate more water, leaving less for the moss to live on.

"We've been finding that the communities are becoming drier. We're also getting a shift of species toward ones that are better able to tolerate desiccation," she said. Robinson and her colleagues reported the environmental effects on the moss colonies in January 2012 in the journal Global Change Biology.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.