Male Birth Control Pill Gets Boost in New Study

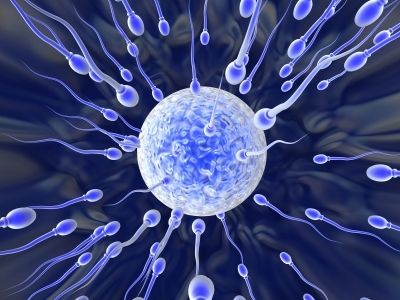

Successful experiments in mice offer new hope in the search for the elusive male birth control pill, researchers report today.

A small molecular compound can induce temporary infertility in mice by targeting the process of sperm formation, or spermatogenesis, according to the study to be published Friday (Aug. 17) in the journal Cell. It will be a long journey to a drug in humans, if that day comes at all, but researchers are hopeful that they have hit on a compound with few side effects.

"No one has ever had a drug that they've been able to test in mice that actually targets the germline, that is the spermatogenic cells, that has reversibility," said study researcher Martin Matzuk, a developmental biologist at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Male contraception

Developing a male birth control pill is more difficult than creating female contraceptives. To render a woman temporarily infertile, all you have to do is disrupt the monthly hormonal cycles that lead to the release of a single egg. Men, on the other hand, produce a "continuous daily wave of sperm" numbering in the millions, Matzuk told LiveScience. [10 Wild Facts About His Body]

Researchers have yet to find the perfect solution to stopping this sperm production in a reversible way. Hormonal methods to stop sperm production have whole-body side effects, and nonhormonal methods such as blocking the body's ability to use vitamin A, a crucial component of sperm production, are still in the early stages. In fact, Matzuk said, the challenges are so stark that many major pharmaceutical companies have given up on trying to develop a male pill.

Matzuk and his colleagues are making the latest attempt with a compound called JQ1, which was originally developed at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. JQ1 binds to a protein called BRD4, which plays a role in some cancers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Coincidentally, a closely related protein called BRDT is produced only in the testes and is crucial to the process of sperm maturation. If JQ1 could also bind to BRDT, Matzuk and his colleagues realized, it might act as a very local way to stop sperm production.

Birth Control has become a hot political topic. Test yourself on your understanding of the pills and devices that prevent pregnancy and STDs.

Birth Control Quiz: Test Your Contraception Knowledge

Developing a pill

The researchers tested JQ1 by injecting the compound into male mice that had access to female mice. They found that the compound sent sperm counts plummeting. After six weeks of low daily doses, for example, male mice had only 11 percent as many sperm as control mice without JQ1 injections, and only 5 percent of the sperm were motile, or capable of swimming.

The same low doses reduced the number of litters sired by the male mice, even as they continued normal sexual behavior. In the first month of breeding, seven male mice not treated with JQ1 sired 14 litters of offspring. Only four of the treated mice became fathers. Once taken off the drug, the mice returned to normal fertility in about two months.

"We show in these studies that not only can we induce a contraceptive effect so the mice are infertile, but when we stop the drug, that spermatogenesis returns and the mice are able to sire offspring," Matzuk said.

To transfer the drug for human use, scientists would have to find a dose that would result in complete infertility among all men, Matzuk said. The compound is promising, Matzuk said, but there is still much more testing to be done.

"This is an early step," he said. "You can say this is the drug discovery stage of working on a male contraceptive pill. We've recently received funding for five years from the National Institutes of Health to further this research."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

'Love hormone' oxytocin can pause pregnancy, animal study finds

'Mini placentas' in a dish reveal key gene for pregnancy