Semen May Trigger Ovulation

A recently discovered protein in semen can cause female mammals to ovulate, new research finds.

The protein has been found in multiple mammal species, including humans, though researchers aren't yet sure what effect it might have on human fertility. In cows, they have found, the substance may contribute to the process that keeps pregnancies viable. The same might be true for humans.

"The whole idea of having a chemical substance in the seminal plasma in the male affecting the female's brain and causing her to ovulate is really new for us," said study researcher Gregg Adams, a professor at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan.

Adams and his colleagues report their findings today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Inducing ovulation

Mammals can be divided into two groups, Adams said: Induced ovulators and spontaneous ovulators. Spontaneous ovulators are those with a regular menstrual cycle, such as humans. These mammals release egg cells on a regular schedule, whether they've copulated recently or not. [Macho Men: 10 Wild Facts About His Body]

Spontaneous ovulators include animals such as camels and llamas that only release eggs in response to sex.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers long assumed that it was the sex itself that induced this ovulation, Adams said. The stimulation of the vagina or some mix of pheromones was assumed to be the culprit. But in 2005, Adams and his colleagues discovered a protein called ovulation-inducing factor in the seminal fluid of llamas and camels. This protein did exactly what its name would suggest, inducing ovulation in females exposed to it.

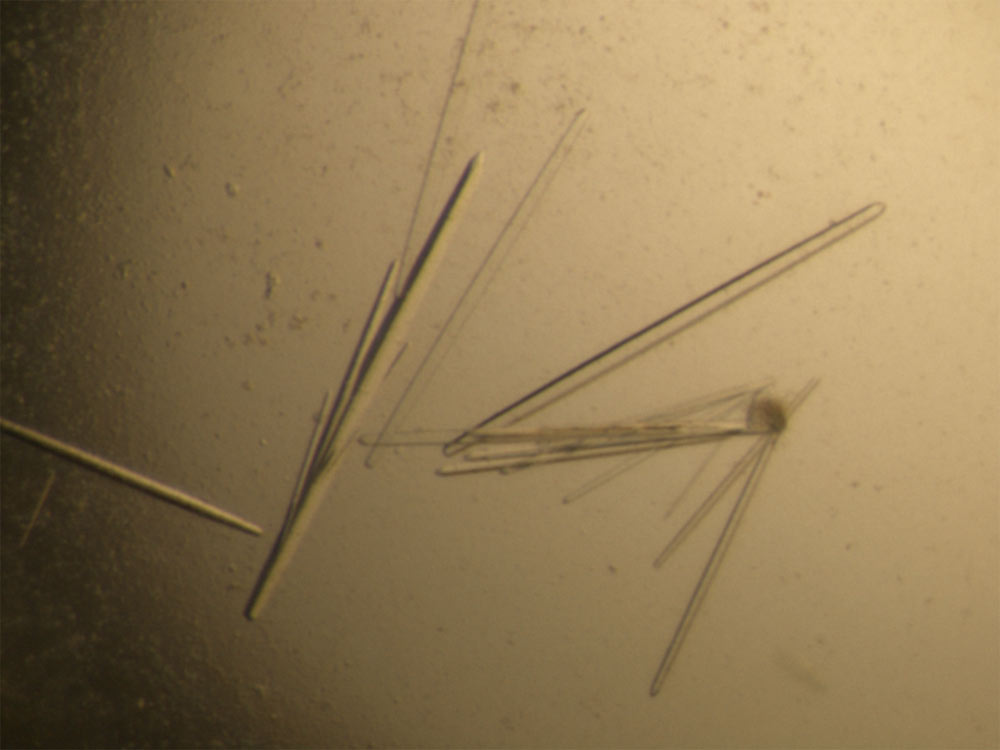

In the new study, Adams worked with researchers from the Universidad Austral de Chile in Valdivia, Chile as well as former University of Saskatchewan graduate student Marcelo Ratto to uncover the identity of this mysterious protein. They isolated it from the semen of llamas, a species of induced ovulators, and from cattle, a species of spontaneous ovulators. The same protein has also been found in every mammal the group has studied, from rabbits and pigs to mice and humans.

Identifying the culprit

A series of biochemical analyses revealed that the ovulation-inducing factor is actually a familiar substance in the body: It's identical to a chemical called nerve growth factor. Nerve growth factor is known to play a role in maintaining the body's nerve cells. Until now, it was only thought to act locally on nerves.

But now, Adams said, it's clear that nerve growth factor has a reproductive function as well. Once introduced into the vagina and uterus, it enters into circulation and travels to the hypothalamus and pituitary gland of the brain, triggering a hormonal response that ends with ovulation, he said.

"This is a new method of action for nerve growth factor," Adams said. "We never thought it could pass the blood-brain barrier."

Fertility and ovulation

The ovulation-inducing factor's role in causing egg release in induced ovulators is clear, Adams said, but it's less obvious what the protein is doing in spontaneous ovulators such as humans. Experiments in cattle suggest that it doesn't cause ovulation directly. Instead, it seems to influence the growth of follicles in the ovaries, the structures from which eggs are released. Most importantly, Adams said, the protein seems to affect the growth of the corpus luteum.

The corpus luteum is a structure that ranges from about an inch to 2 inches in size (2 to 5 centimeters). It forms from the collapsed follicle after an egg is released and produces the hormone progesterone, which is crucial for maintaining pregnancy.

"A lack of progesterone is implicated in sub-fertility in a lot of species, including women," Adams said.

In other words, the findings suggest that the composition of a male's semen may influence whether the female's pregnancy is successful. Adams and his colleagues are now conducting animal studies to investigate whether the quantity of ovulation-inducing factor in a male's semen affects his fertility.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappasor LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook& Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.