Ingredients for Big Black Holes Detected in Milky Way's Core

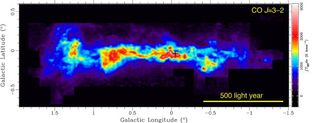

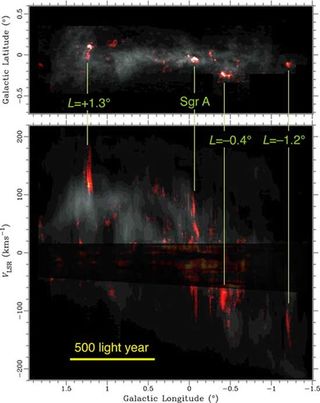

Scientists investigated our galaxy's central molecular zone, which contains the most massive, densest, and most turbulent molecular clouds in the Milky Way. These surround the heart of our galaxy, which is suspected to be home to a supermassive black hole about 4 million times the mass of the sun.

The central molecular zones of galaxies crowd lots of gas close together, making them good places for stars to form. To learn more about these lively regions, scientists used radio telescopes to compile detailed maps of the temperature and density of clouds at the Milky Way's heart.

Now scientists have discovered four giant clumps of gas that appear to be the kinds of seeds intermediate-mass black holes arise from. These black holes hundreds to thousands of times the mass of the sun that are thought to in turn serve as the building blocks for the supermassive black holes found in the centers of galaxies.

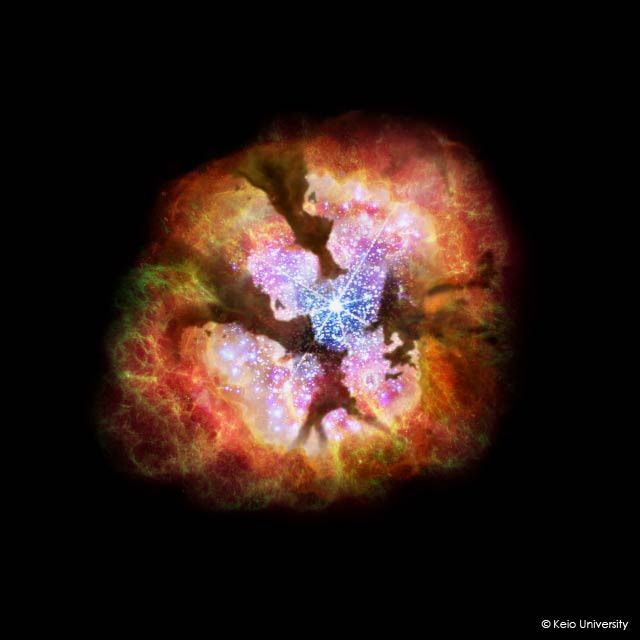

The clumps are each about 30,000 light-years away. One of the masses contains the black hole suspected to exist at the heart of the Milky Way. This disk-shaped clump is about 50 light-years across "and revolves around the supermassive black hole at a very fast speed," said study lead author Tomoharu Oka, an astronomer at Keio University in Japan. [Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

The other three clumps are expanding at very fast speeds of more than 223,000 miles per hour (360,000 kilometers per hour), making the researchers think supernova explosions were the cause of this growth, with the fastest blooming of these clumps growing as if 200 supernovas went off inside it. Since the age of this clump is only thought to be about 60,000 years old, which suggests supernovas happened there every 300 years.

Such a high rate of supernovas suggests that many young, massive stars are concentrated inside. The researchers estimate a massive star cluster more than 100,000 times the mass of the sun lurks within, as big as the largest star clusters in the Milky Way.

"No matter how large the star cluster is, it is very difficult to directly see the star cluster at the center of the Milky Way galaxy," Oka explained. "The huge amount of gas and dust lying between the solar system and the center of the Milky Way galaxy prevent not only visible light, but also infrared light, from reaching the earth. Moreover, innumerable stars in the bulge and disc of the Milky Way galaxy lie in the line of sight."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Huge star clusters at the center of the galaxy are where intermediate-mass black holes several hundred times the mass of the sun are expected to form.

"Many galaxies with central molecular zones may harbor such young massive clusters," Oka told SPACE.com.

"The new discovery is an important step toward unraveling the formation and growth mechanism of the supermassive black hole at the Milky Way galaxy's nucleus, which is a top-priority issue in galactic physics," he added in a statement.

It remains uncertain how many intermediate-mass black holes might lurk in the central molecular zones of galaxies, or at what rates they are created. "Further investigations of the central molecular zones of our galaxy and other galaxies will reveal them," Oka said. Specifically, the Atacama Large Millimeter/sub-millimeter Array (ALMA) of radio telescopes may detect intermediate-mass black holes, he added.

The scientists detailed their findings in the August issue of the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.