Jury's In: Law School Test Messes with the Mind

Intensely studying for the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) can improve one's chances of getting a high score, but it can also change brain structure and may even boost IQ, neuroscientists say.

"The fact that performance on the LSAT can be improved with practice is not new. People know that they can do better on the LSAT, which is why preparation courses exist," lead researcher Allyson Mackey, of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. "What we were interested in is whether and how the brain changes as a result of LSAT preparation, which we think is, fundamentally, reasoning training. We wanted to show that the ability to reason is malleable in adults."

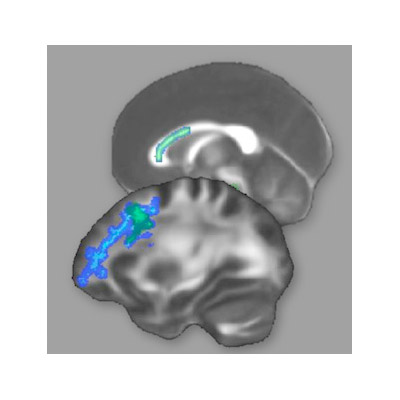

Mackey and her team looked at brain scans of 24 college students or recent graduates before and after 100 hours of LSAT training over a three-month period, a statement from Berkeley explained. Compared with brain scans of a control group of their peers, the trained students showed increased connectivity between the frontal lobes of their brains, and between the frontal and parietal lobes. These circuits are involved in fluid reasoning, or the ability to tackle new problems, which is central to IQ tests.

Past research has suggested that highly connected brains make for highly intelligent people. That's because such connections allow a person to literally make "mental leaps" between different brain regions. "For the intelligent aspects of cognitive processing — thinking hard — the network that we need in the brain is highly distributed over space," Edward Bullmore, a neuroscientist at Cambridge University in England, told Life's Little Mysteries last year. "Consciously performing some difficult model task … relies on connections forming over long anatomical distances."

The new study, detailed online Wednesday (Aug. 22) in the open access journal Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, suggests not only that these brain pathways are plastic in adults, but also that a person's IQ can change.

"A lot of people still believe that you are either smart or you are not, and sure, you can practice for a test, but you are not fundamentally changing your brain," study researcher Silvia Bunge said in the statement from Berkeley. "Our research provides a more positive message. How you perform on one of these tests is not necessarily predictive of your future success, it merely reflects your prior history of cognitive engagement, and potentially how prepared you are at this time to enter a graduate program or a law school, as opposed to how prepared you could ever be."

The research was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health, with the assistance of Blueprint Test Preparation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.