Stellar Triggers of Exploding Stars Revealed

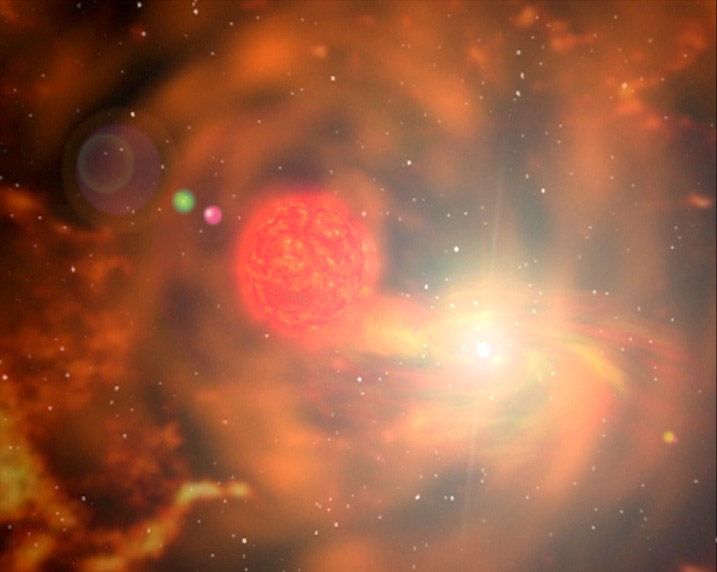

Mysterious stars that incite their stellar companions to explode in spectacular supernovas have just been revealed — these culprits can be bloated red giants, researchers say.

Supernovas are exploding stars that are bright enough to briefly outshine all the stars in their galaxies. They can occur when one star sheds gas onto a dying star known as a white dwarf, the dim fading core of a star that was once about the size of our sun.

Eventually, all this extra gas increases the white dwarf's mass enough to trigger runaway nuclear reactions that detonate the white dwarf.

The nature of the white dwarfs' companion stars in these explosions, which are a rare type of stellar conflagration dubbed a Type 1a supernova, is hotly debated, since researchers have not directly observed these companions. To learn more, astronomers used observatories in California, Hawaii, Arizona and the Canary Islands to investigate the supernova PTF 11kx, which is about 675 million light-years away. [Amazing Photos of Supernova Explosions]

Red giant star trigger

The scientists observed the complex shells of gas closely surrounding this supernova in very fine detail. This material from the white dwarf's companion star yielded insights regarding the identity of its source.

"We really saw for the first time detailed evidence of the progenitor for a Type 1a supernova," study lead author Benjamin Dilday, an astronomer at Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network in Goleta, Calif., told SPACE.com.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers suggest the companion was a red giant star, much like what our sun is expected to become in about 5 billion years. As this red giant swelled with age, this matter poured on its white dwarf companion, occasionally triggering explosions known as novas. Enough material eventually poured onto this white dwarf to set off a far more powerful supernova. The researchers estimate that novas give rise to more than one-tenth of a percent of all type 1a supernovas, but less than 20 percent.

Past evidence suggested that only merging white dwarfs could cause Type 1a supernovas. The new findings suggest these kinds of explosions can involve many different kinds of stars.

"It is a total surprise to find that thermonuclear supernovae, which all seem so similar, come from different kinds of stars," said study author Andy Howell at Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network. "It is like discovering that some humans evolved from apelike ancestors, and others came from giraffes."

The new study also suggests that studying smaller star explosions called novas, which don't entirely destroy the star, might also shed light on Type 1a supernovas.

"We may be able to gain a better understanding of supernova 1a progenitor systems in general," Dilday said.

Cosmic candles in the night

Type 1a supernovas are ideal for measuring cosmic distances. They always erupt from white dwarfs of certain masses, and so always have the same relative brightness.

This predictability makes them extraordinarily valuable in figuring out how far away their host galaxies are — scientists compare how bright they know these explosions should be with how bright they appear to calculate the distance of the supernovas and their galaxies.

Knowing the distance of far-flung galaxies helps astronomers better understand how the universe evolved, and as such, learning more about Type 1a supernovas could help shed light on cosmic mysteries such as the dark energy that is apparently causing our universe's expansion to accelerate, Dilday said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Aug. 24 issue of the journal Science.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.