Nanotech's Ill Effects on Small Sea Creatures Stir Concern

A high-tech material called carbon nanotubes is harmful to the growth and lifespan of small animals important to ocean life, a new study has found. However, cleaning the nanotubes of impurities may go a long way toward reducing their toxic effects on sea life, the study added. The research is in the first wave of simple experiments on the effects of nanotechnology on the environment.

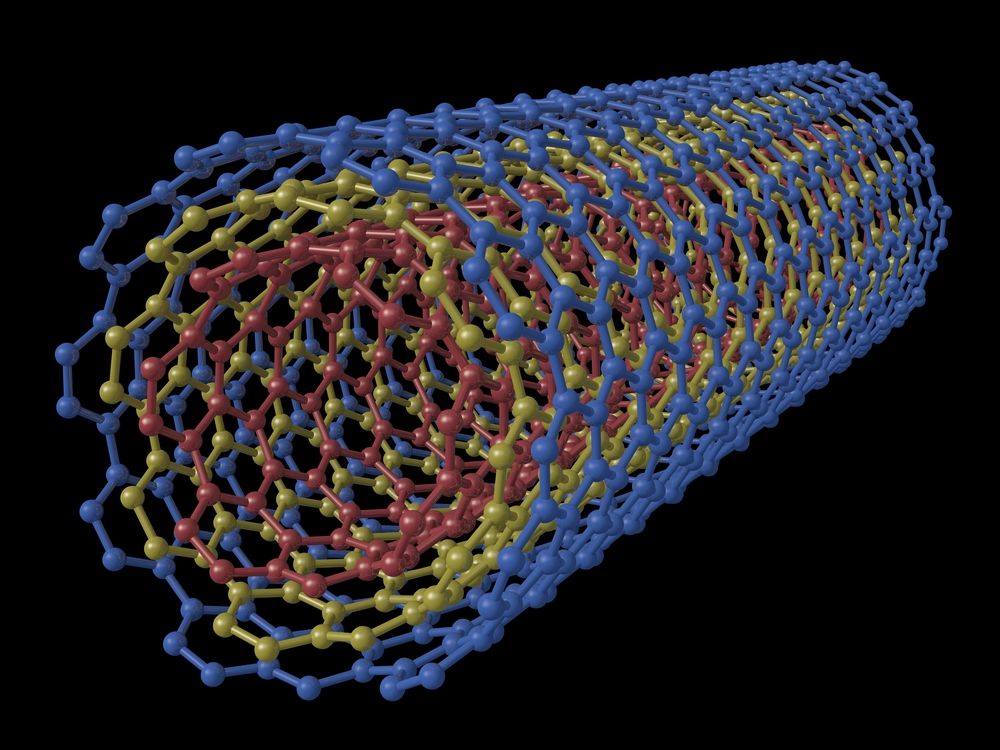

Right now, carbon nanotubes are not a commonly used — or dumped — material. They do appear in high-end sports equipment such as tennis rackets and in experimental airplane parts. In the future, however, experts think the tiny tubes, made of rolled-up sheets of carbon just one atom thick, will likely show up in many more items. Carbon nanotubes are being developed for super-efficient solar panels and water filters, as well as for creating lightweight, but strong, materials.

"If the application side grows, potentially we would have much, much more material, then that would be a concern," Baolin Deng, a chemist and engineer at the University of Missouri who led the new research, told InnovationNewsDaily. "If we can make a better product with carbon nanotubes, great, I'm all for that. But at the same time, we really need to look at the potential impact of those materials, so we will not be surprised in the future."

Deng's study shows the separate effects of carbon nanotubes and the metal impurities that are usually stuck on the nanotubes' surfaces after manufacturing, said Desiree Plata, a researcher who studies chemicals in the environment at Duke University in Durham, N.C. (Plata was not involved in Deng's study.) At the same time, several aspects of the study don't accurately mimic what is likely to happen to nanotubes in nature, so more accurate tests of carbon nanotubes are needed, she said.

Carbon nanotubes in lab

For their study, Deng and his colleagues chose four species of small ocean and estuary creatures that scientists know are sensitive to chemicals in their environment and are important to other animals in the ocean. They put the animals, including one species of mussel and a crustacean a few millimeters in length, in tanks in a lab.

The researchers then added carbon nanotubes to some of the tanks so that the water had a 1 percent concentration of nanotubes. They measured how many animals survived and how much they grew.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found the nanotubes reduced the growth and lifespan of the animals. When they tried cleaning the nanotubes before adding them to their tanks, they found more of the animals survived, but they still grew less than animals grown in tanks without carbon nanotubes. [10 Ways You're Using Nanotech Right Now (And Don't Even Know It)]

Other researchers have shown that carbon nanotubes affect the growth of small marine animals, but because toxic metals are used to manufacture the tubes, scientists weren't sure if the tubes' effects might just be from the manufacturing chemicals."What we found is that both the carbon nanotubes and the impurities contributed to the toxicity of this material," Deng said.

Yet simply cleaning the tubes may help reduce some of their effects. "Cleaning those materials may not be that difficult," Deng said. He recommends manufacturers clean off toxic chemicals before putting carbon nanotubes into golf clubs, solar panels or anything else.

On the other hand, Plata said that Deng's study is a first step that may be difficult to translate into many lessons for real life. The amount of nanotubes Deng and his colleagues added to their animals' tank is a billion to a trillion times greater than what scientists expect from factory emissions and the degradation of nanotube products in landfills, she said. "There would never be a case where you would have a concentration of that in a sample," she said.

Although many people may expect that a higher-concentration study would exaggerate the ill effects of a chemical, in the case of carbon nanotubes, too many nanotubes may actually reduce the negative consequences of the material to ocean animals. At high concentrations, nanotubes tend to clump together and act as if they were larger particles. Such clumps reduce animals' exposure to the nanotubes, so the clumps may appear less toxic than the individual particles that exist at the lower concentrations researchers expect, Plata said. [The Perils of Small Stuff: What We Know About Nanotech Safety Today]

Deng, on the other hand, thinks his study accurately mimics what might happen outside the lab. Carbon nanotubes tend to fall to the bottom of water and clump, he said. They may be show up in very high concentrations in some locations, he said.

Are new laws needed?

One thing both Deng and Plata agree upon: With what scientists know now, it's difficult to say if carbon nanotubes need additional laws regulating their disposal.

Deng would like to see studies on where exactly carbon nanotubes would go when they're released in water. Do they fall to the bottom of the water? Do they really clump thickly in certain areas?

Plata argued that researchers should study carbon nanotubes at the concentrations closer to the ones experts think are likely to occur. She also noted that lab tanks oversimplify what would happen in the open ocean. "That would be ok if we knew how to take the simple case and translate it to the complex case, but we are not there yet," she wrote in a later email to InnovationNewsDaily.

"Most of the toxicity studies that have been done in aquatic and sedimentary systems are really at concentrations that are too high to know if anything is going to have an effect," she said. "But they suggest caution."

Deng and his colleagues published a paper on their research in June, in the journal Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily staff writer Francie Diep on Twitter @franciediep. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.