Earth Supports One-Third Less Life Than Thought

The total mass of life on Earth may be one-third less than thought, altering how active we think life on our planet is, researchers say.

Past estimates of how much life there is on Earth suggested living organisms store about 1 trillion tons of carbon, of which about 30 percent dwells in single-celled microbes in the ocean floor, and about 55 percent rests in land plants.

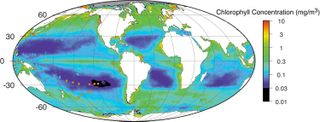

However, it turns out previous estimates of the amount of life in the ocean floor were based on samples taken in very nutrient-rich areas, such as close to shore. About half the world's ocean is extremely nutrient-poor, meaning that comparably little in the way of life should be found there.

"For the last 10 years it was already suspected that sub-seafloor biomass was overestimated," said researcher Jens Kallmeyer, a geomicrobiologist at the University of Potsdam in Germany and the GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences. "Unfortunately there were no data to prove it."

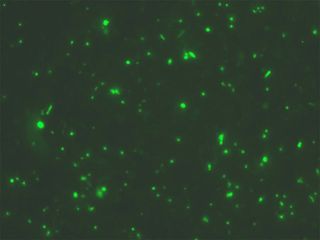

Over the course of six years, Kallmeyer and his colleagues analyzed data on counts of seafloor microbes and collected sediment samples from ocean sites far away from any coasts and islands. Their findings revealed there was up to 1 million times more cells in coastal sediments than in sediments from open-ocean areas — known as the "deserts of the sea" due to their scarcity of nutrients.

"The huge variability of microbial abundance between sites has really struck me," Kallmeyer told LiveScience. "It was expected for several years now that there is greater variability than previously thought, but not to that huge extent."

All in all, the researchers estimate about 4 billion tons of carbon are stored in microbes in the ocean floor instead of 300 billion tons. This reduces the estimated amount of the world's biomass drastically by about a third. [50 Amazing Facts About Earth]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kallmeyer and his colleagues now want to consider the age of the sediments where microbes dwell as well, since different parts of the ocean may change and operate on very different time scales.

"For example, a cell in 2-meters (6-feet) depth in the South Pacific Gyre may reside in 20-million-year-old sediment, whereas the same age in a coastal sediment would be in over 100-meters (330 feet) depth," Kallmeyer said. "There are huge differences in sedimentation rates, and they have to be taken into account." (Sedimentation rates, or the rate at which new sediments cover older ones, influences the age of layers at the seafloor surface.)

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Aug. 27) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.