Sea Lights Help Seals Hunt in the Dark

The glow that certain fish give off may help the world's largest seals hunt them down.

Southern elephant seals spend about 10 months in the southern Indian Ocean, coming ashore only to breed and molt. They forage over broad distances, during which time they dive continuously, sometimes deeper than 4,900 feet (1,500 meters).

The deep, dark ocean is a challenging place to find prey. Whales use echolocation — the biological equivalent of sonar — to scan for potential food, while penguins rely on scent. However, it remained uncertain how southern elephant seals foraged in the deep sea. Scientists now have a better idea after attaching electronic devices to some of them.

Shining a light on prey

Southern elephant seals are the world's largest seals. "Standing next to a male over 3 tonnes (6,600 pounds) and 4 meters (13 feet) long is particularly impressive," researcher Jade Vacquié-Garcia, a marine biologist at the Center for Biological Studies of Chize in France, told LiveScience.

The elephant seals primarily prey on lanternfish, which are bioluminescent — they naturally give off a glow. The glow helps the fish communicate with other members of their species; it also allows them to startle predators and to hide from carnivores lurking underneath by mimicking the light from above. [Bioluminescence: A Glow in the Dark Gallery]

Past research showed the vision of these seals is specialized to weak light, with peak sensitivity for the same blue light that lanternfish give off. Scientists who tagged southern elephant seals in the southern Indian Ocean were surprised to find these seals may track lanternfish by sight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

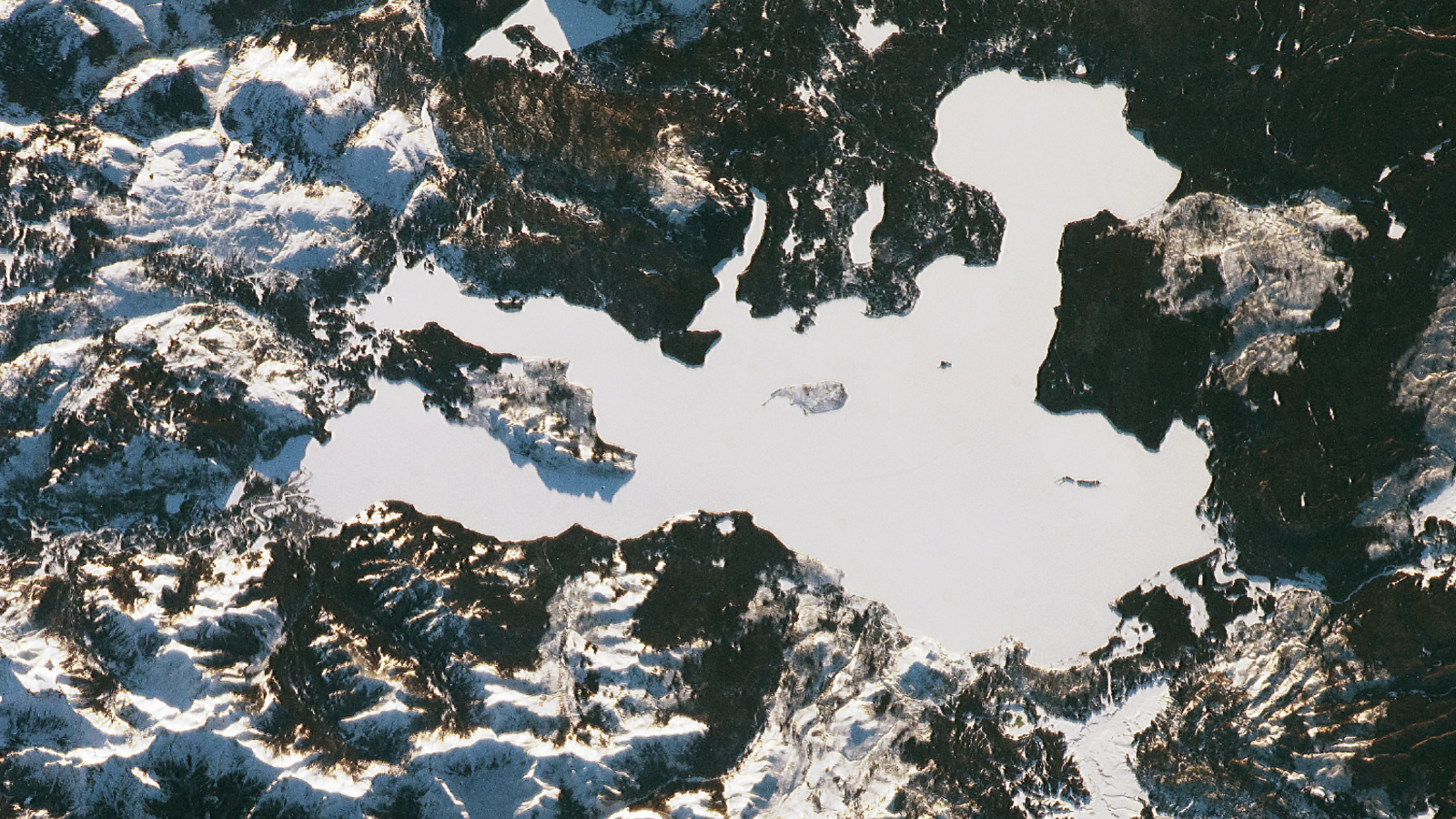

"Each year about 10 tags are deployed on seals in Kerguelen Islands, French territories in the southern Indian Ocean," Vacquié-Garcia said. "We leave for several months, living on an island swept by storms from the Southern Ocean where the seals come onshore twice per year. The experience is unique and very exciting."

In addition to the seals, "the seabird colonies are also very numerous — albatrosses, penguins," Vacquié-Garcia said. "This is one of the few places in the world where we are confronted with the wild world with such intensity. It is a real privilege."

The scientists anesthetized four female seals and glued electronics onto their heads. These devices included satellite tags that relayed temperature and other data, as well as sensors that monitored light and recorded the depth and lengths of dives.

"The initial topic of the study was absolutely not dedicated to bioluminescence," Vacquié-Garcia said. "The light sensor was originally aimed to see if there was a link between the depth of penetration of light from above and how productive a depth was," in terms of life in that layer.

Foraging with light

The researchers analyzed a total of 3,386 dives and deduced that seals found good areas to forage based on how fast they ascended from those areas and dove back to them.

Increased bioluminescence deep underwater, where there was no light from above, was linked with foraging. This suggests these glows help the seals forage more and find prey.

"We had confirmation that without really wanting to, we had recorded the events of bioluminescence along the dive tracks of seals," Vacquié-Garcia said.

Future research could aim to identify with certainty what bioluminescent species the seals encountered, and how bioluminescent events change around the seals as they swim.

The scientists detailed their findings online Aug. 29 in the journal PLoS ONE.