Paleo-Artists Breathe Life, and Color, into Dinosaurs

Dinosaurs, the mystical and often fierce giants that once roamed planet Earth, seem to come alive in the minds of many a child. It was this imagination that led one young dino enthusiast to attempt to bring these paleo-beasts to life through his science-based illustrations.

Steve White, a British comic books editor and paleoartist, has been drawing dinosaurs since he was young. This "childhood fixation," as he calls it, never left him. The latest manifestation is his new book, "Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart" (Titan Books, Sept. 2012). LiveScience caught up with White to find out what drives him and the amazing artists portrayed in the book, some of whom are also scientists, as well as what he sees as the future of drawing dinosaurs and ancient mammals.

LiveScience: Why did you decide to put together this book? And what kind of story are you trying to tell?

Steve White: The idea for the book was spawned from seeing so many collections of natural history art that never included paleoart. To be honest, I find a lot of natural history illustration something of a cheat — it's essentially the artist using whatever medium they choose to transfer a photo into art. Much of it is also very dull — essentially still life. [See Images of the Amazing Dinosaur Art]

I had come to conclude that a great many paleoartists were as good if not better than their 'modern' contemporaries, but the only time you got to see their work was in popular dinosaur books or academic paleontology tomes. I really wanted to do something that highlighted them as artists and gave them an opportunity to discuss their own methods and styles, whilst producing something beautiful enough to attract the passing fancy of someone who just loved good art.

LS: How did you get into paleoart, and what was your first drawing/piece of artwork?

White: I've drawn dinosaurs since I was small child and even been lucky enough to make a living at it, at least for a while. My first efforts (as I recall) were copies of simple black-and-white drawings that were done as part of a timeline in the appendices of an animal encyclopedia illustrating the evolution of life. They were pretty much my introduction to dinosaurs — and drawing. From then on, I developed one of those childhood fixations — which has never actually left me. I suspect the same is true of many paleoartists ...

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

LS: Why did you not include more of your work in the book?

White: I guess it would have felt a little self-serving. The only reason I could in all good conscience have done would to have proved to casual readers I wasn't some yahoo playing dinosaur artist! But, no, it was just a judgment call on my part, even though many of my friends and colleagues here at Titan thought I should have included more.

LS: You mention that Robert Bakker and Gregory Paul transformed dinosaur paleontology and reconstruction, calling it a Dinosaur Renaissance. What did you mean?

White: To me, Bakker and Paul were the "Renaissance Men." Bakker was a student of famous paleontologist John Ostrom who, in a 1969 monograph on a small predatory dinosaur named Deinonychus, implied that maybe dinosaurs were not as trenchant dogma at the time perceived them; slow, dimmed-witted, cold-blooded monoliths to failure, lumbering toward the sunset of extinction. He saw in Deinonychus an advanced, agile killer with some very sophisticated features. He also saw a clear link between these dinosaurs to birds. Bakker then produced a whole series of papers that shock the pillars of dinosaur heaven, and in doing so triggered a cascade effect in research that became known as the "Dinosaur Renaissance;" he suggested that dinosaurs were warm-blooded organisms far closer in anatomical style to birds and mammals than to reptiles (this is, I should point out, not to say they are closely related to mammals!).

As he was also a pretty dab hand with a pencil he produced a slew of wonderful drawings showing them as active, dynamic, colorful creatures — living creatures. From my own personal perspective it was seeing these for the first time, in about 1977, that really reignited my passion for dinosaurs, which had been on the wane somewhat at this point, losing out to Star Wars and Jaws. [Image Gallery: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly]

I remember first seeing Greg Paul art in a feature he illustrated in, I think, Scientific American; lovely full-color art but once again, showing the dinosaurs as animals in the truest sense; they looked plausible. You could imagine these animals being alive. You have no idea of the significance of this. Up until then, the great paleoartists had been just that — artists. While many of the "greats" such as Charles R. Knight are still venerated, their dinosaurs are seen as "quaint;" their prehistoric mammals have weathered the test of time far more effectively. Before the Renaissance, there was no real effort to get to grips with dinosaur anatomy, biology or ecology, and the art suffered accordingly (not the fault of the artists, I might add; dinosaur research at this time was in a sort of stasis, and the view of them as "great reptiles" had really taken hold). Bakker and Paul were really the first two to dismantle dinosaurs down to the nuts and bolts, then use that knowledge to breathe life into them. This was of course aided by the fact they are both superb artists.

LS: What makes a successful piece of dinosaur art, or other paleoart?

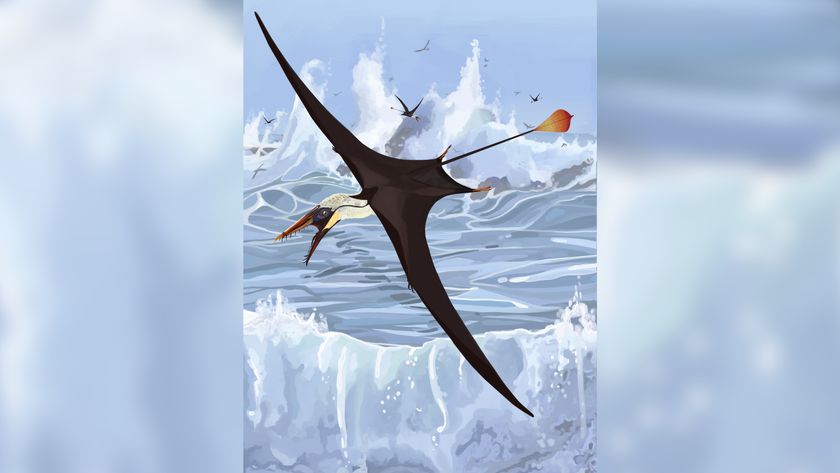

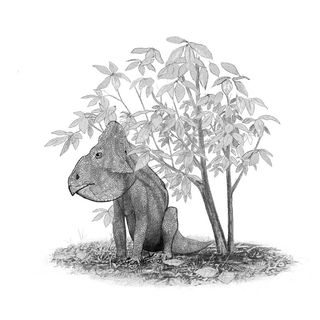

White: Hmmm… I guess it's just making the subject matter look believable. Not every dinosaur lived in a jungle in the shadow of an erupting volcano, with a Pteranodon soaring overhead. This tends to be the default setting in the public eye (in my humble opinion anyway). The most successful illustrations are those that take on the environment as a whole. It's not just making the animal look anatomical accurate; it's about making it look part of the ecology that works it. The trees have to be right. What kind of habitat did it live in? What sort of undergrowth was there? What other non-dinosaurian animals lived alongside it? All this combines to make a plausible whole. You're doing the prehistoric version of Constable's The Hay Wain.

LS: That said, what are some of your favorite pieces of artwork in the book? Why do these stand out?

White: Hehe. Loaded question... "I love them all..." he says, nervously. There are a couple that really do stand out for me. Doug Henderson has always been one of [my] favorite paleoartists; he has been a major influence on my own work. There was one piece that really stood out, which we ended up using to open his section; that of Elasmosaurs, long-neck marine reptiles, caught in the curl of a wave with sun behind them, while a flight of Pteranodons pass overhead. Just such an innovative idea so beautifully executed. The other was by John Conway; a pair of small predatory dinosaurs called Troodon standing very much in the shadow of a magnificent Magnolia bush. The colors were so striking, so gorgeous. And such an unusual idea. [Album: Troodon Dads Care for Young]

LS: Who knew a paleoartist painted album covers for Motley Crue and other heavy metal bands?! Did you learn anything else surprising from your interviews with the artists?

White: I learnt an awful lot. Doug Henderson is an amazing landscape photographer (we included a couple of his images but there's a book in his photos alone!). It was also interesting to contrast and compare reconstructions of the same animal by the different artists, and look at the varying approaches they took to the same problem — what did the animal look like in the flesh. Similarly, the very broad approach to the testy issue of transiting from traditional mediums to The Computer. This has been a momentous time in paleoart as many established artists make the switch, while you have a whole new generation, who have grown up computer-literate, are on the rise. One look through DeviantArt and you can see the future right there.

LS: For those who may want to try their hand at dino art, what's the behind-the-scenes knowledge you need to do it right?

White: Paleoartist Luis Rey once told me that Bob Bakker said to him, "No one should be drawing dinosaurs until they'd dissected a chicken and an alligator." I think many artists would be hard-pressed to find enough alligators for the purpose but I guess, in Bakker's view, anatomy is very important. Paleoartists don't have the benefit of vast selections of photographs — or even the living subjects — to illustrate their subjects like Natural History artists. It's far more theoretical but that doesn't mean you should skimp on the pate and not do your research. But anatomy is really just one aspect; as I alluded to before, it's about the broader picture, so to speak; environment, flora, fauna, ecology. It's not just about constructing the animal; it's about constructing the entire world.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.