'Princess Scientists' Stir Controversy

Whenever Erika Ebbel Angle shows up wearing her Miss Massachusetts tiara at tapings of her television show, all the kids in the live studio audience go "Oooooh!" But it takes more than a tiara to define Angle: She's an MIT graduate with a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Boston University and the founder of the nonprofit organization Science from Scientists, as well as the host of a 10-minute science show on regional cable TV. And she's preparing to enter the entrepreneurial world with her own biotech startup.

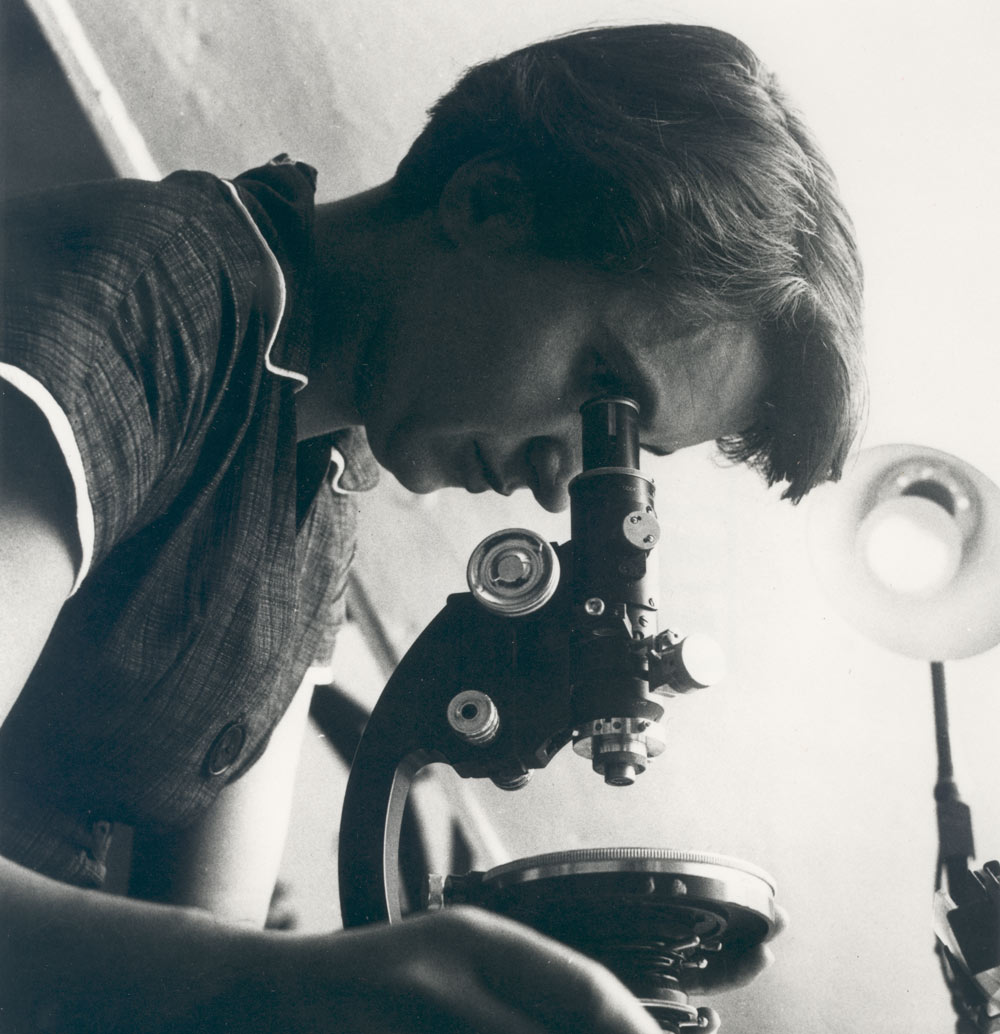

The value of beauty and brains combined is rarely emphasized outside Hollywood, but early feedback from "The Dr. Erika Show" suggests many younger girls have embraced the message Angle is sending when she pairs the pageant tiara with a lab coat in her eponymous TV show. Girls have told the show's producers they want to become "princess scientists."

"Science comes with a stigma that if you are a female scientist, you have no other interests and you are a sweatpants-wearing person who has no interest in your own physical appearance or maintenance," Ebbel Angle said.

In Japan, a similar desire to combat the geeky stereotypes of science drives the "Miss Rikei Contest," organized by a student group and scheduled for Sept. 12. Six female finalists chosen from among Japanese university students and researchers will compete for votes based on the criteria of beauty, intelligence and making contributions to improving the image of science. ("Rikei" means "science" in Japanese.)

But female scientists may resent the idea that their physical appearance is up for scrutiny at all. Scientists of both genders are just as varied in appearance as those in any other profession, and several researchers interviewed by LiveScience suggested style choices shouldn't be nearly as discussion-worthy as their work. [5 Myths About Girls, Math and Science]

Efforts to incorporate feminine beauty into the role model for scientists can also touch a sensitive nerve because women have fought so long to get beyond female stereotypes in the historically male-dominated fields of science and engineering. While Ebbel Angle's TV show focuses on helping out students with their science projects or investigating science questions, the pageant-style format of the Miss Rikei Contest has received more mixed reactions.

Beauty and the geek

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Miss Rikei Contest caused a minor stir among U.S. scientists, journalists and educators after Joanne Manaster, online course developer and lecturer of science courses for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, alerted her Twitter followers to the pageant's existence.

"One of the websites I found [discussing the contest] included comments that were all from men who were viscerally reacting to the pretty women," Manaster said. "I think this bothers people who are in science, especially women who want to be taken seriously."

Organizers of the Miss Rikei Contest did not respond to requests for comment. But LiveScience also asked the opinions of three young Japanese women who received bachelor's degrees in science or engineering from universities in Japan. Two of the three agreed to comment only on condition of anonymity.

"Yukari," a biology researcher at a university in New York City, called the Miss Rikei Contest "superficial" and resisted the idea of trying to make science appear more overtly feminine, in the stereotypical sense of the word.

"I rather like the idea that it's an oasis for geeky people that doesn't much care about what the rest of the world is concerned about," Yukari said. "There's something about science for me that overrides this image of male-dominant and geeky, so that if you can see how important or fun science is, it doesn't matter if it's male-dominated or geeky or doesn't pay as much as finance."

"Rin," a neuroscience researcher at a university in New York City, predicted the Miss Rikei Contest would prove ineffective as a means of encouraging more Japanese women to pursue science careers. [Mommy Track: Why Women Leave Science, Math Careers]

"Any female scientists who have done great work in their field could be great models for young students," Rin said. "These scientists don't have to be like a super-model or actress."

Kanae Kobayashi, who is working for a Japanese securities company after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in industrial engineering, shrugged off the contest as harmless — "seems like fun" — but she, too, thinks it will do little to encourage young women to pursue science careers.

Helpful or harmful

Harmless or ineffective is one matter. But can promoting the ideal of female beauty and brains actually discourage girls or young women from pursuing science? That possibility arose from a University of Michigan study in the March issue of the journal Social Psychological & Personality Science.

The study found that feminine role models decreased girls' interest and ability in math, and also lowered their expectations of success in the short run. Such "beauty-focused" role models also discouraged future plans to study math among girls who had not previously identified an interest in science, technology, engineering or math.

Diana Betz and Denise Sekaquaptewa, the psychology researchers behind the Michigan study, noted that past research by Sapna Cheryan, a psychology researcher at the University of Washington, confirmed how "geeky role models" also can discourage women in fields such as computer science.

So what's a female role model to do?

"On the surface, it might look like a 'Damned if you're feminine, damned if you're not' situation," Betz and Sekaquaptewa told LiveScience in an email. "But really, it's about extremes: Role models should broaden examples of who can succeed in different fields, not limit them to one stereotyped image or another."

The researchers suggested that girls and young women need to see diversity among female role models so that they don't associate science with just one type of person — whether that type is "geeks" or "girly girls."

"Perhaps the best way to encourage girls to explore math and science is to expose them to real female mathematicians and scientists," Betz and Sekaquaptewa wrote. "Girls need to learn that scientists are real, complex people, just like them, and that they have diverse kinds of jobs with varied goals." [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

The pair also pointed out that what discourages girls or young women is an unattainable ideal, but added that the idea of "unattainable" may change among different age groups. That's why young girls may idolize "Dr. Erika" for her pageant poise and science smarts even as middle-school girls turn away with resignation from super-model role models in science.

Giving science a makeover

Feminine stereotypes historically have haunted women scientists, including Rosalind Franklin, a co-discoverer of DNA. In his 1968 account "The Double Helix," James Watson, one of the genetics pioneers who had relied on Franklin's work, unflatteringly recounted Franklin's lack of lipstick and her unwillingness to dress in a more feminine manner.

But the idea of combining "beauty and brains" may represent progress of sorts. Two decades ago, Teen Talk Barbie was telling young American girls, "Math class is tough." The Miss Rikei Contest stands directly opposed to that message, as does Ebbel Angle's encouragement of young girls who want to become princess scientists.

Ebbel Angle defended the pageant idea behind the Japanese contest, but was careful to distinguish between beauty pageants (Miss Universe) and scholarship pageants (Miss America). She told of appreciating the social skills and confidence that came from competing over several years to become Miss Massachusetts after her friends at MIT initially signed her up for a local pageant without her knowledge.

"From what I can read about the Miss Science program, it gives them a chance to prove they have beauty and brains," Ebbel Angle told LiveScience. "I see nothing wrong with that. These are grown women who are in graduate programs and undergraduate programs, deciding what they want their image to be."

In the end, Ebbel Angle sees the pageant crown as a symbol of possibility — girls and young women having the ability to love science and also be dancers, musicians, soccer players or whatever they desire. "It's less about the crown, more about the message," Ebbel Angle said.

Manaster, the science educator who alerted so many people to the Miss Rikei Contest through Twitter, acknowledged her own appearance can make a difference when she does science outreach on TV or at an engineering camp for girls — she is a former fashion model. But she emphasized the importance of focusing on the love of doing science.

"Maybe it's enough to show women scientists who are passionate about their work," Manaster said. "Do science if you love it, and if you happen to be feminine, that's great. If you're not, that's great too."

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow LiveScience on Twitter @LiveScience, or on Facebook.