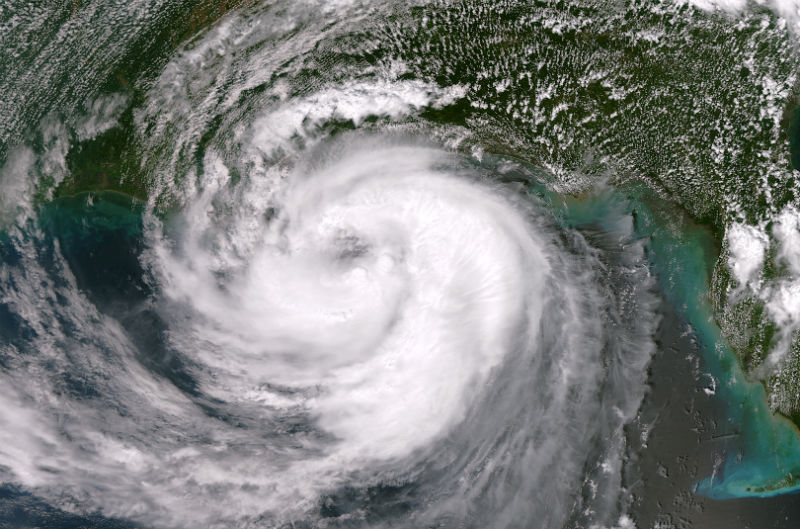

Hurricanes Whip Up Faster in Warming World, Study Suggests

Global warming may fuel stronger hurricanes whose winds whip up faster, new research suggests.

Hurricanes and other tropical cyclones across the globe reach Category 3 wind speeds nearly nine hours earlier than they did 25 years ago, the study found. In the North Atlantic, the storms have shaved almost a day (20 hours) off their spin-up to Category 3, the researchers report. (Category 3 hurricanes have winds between 111 and 129 mph, or 178 and 208 kph.)

"Storms are intensifying at a much more rapid pace than they used to 25 years back," said climatologist Dev Niyogi, a professor at Purdue University in Indiana and senior author of the study.

The work helps support the theory that rising ocean temperatures have shifted the intensity of tropical cyclones, which include hurricanes and typhoons, to higher levels. In the past century, sea surface temperatures have risen 0.9 degree Fahrenheit (0.5 degree Celsius) globally. Scientists continue to debate whether this increase in temperature will boost the intensity or the number of storms, or both. Globally, about 90 tropical cyclones, on average, occur every year.

Storms getting stronger

Tropical cyclones form when warm, moist air over the ocean surface fuels convection. The storms act like heat engines: The warmer the ocean surface, the more energy there is to power a storm's fierce winds. As such, scientists have hypothesized global warming and the associated rising heat of sea surfaces would fuel intense hurricanes.

Most of the initial strengthening of storms, from Category 1 to Category 3, happens on the open ocean, not as a storm is approaching land. So even if storms are intensifying more quickly, it may not result in higher peak wind speeds and more rainfall when hurricanes make landfall. (Category 1 storms have wind speeds of at least 74 mph, or 119 kph.) [5 Hurricane Categories: Historical Examples]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Niyogi and his colleagues found an overall shift toward more intense storms in all ocean basins except the East Pacific. "They are getting stronger more quickly, and also higher category. The intensity as well as the rate of intensity is increasing," said Niyogi. And that makes it a simple numbers game – with more strong storms forming in the oceans, the chance of having powerful hurricanes hit the coast rises.

"If storms in general are intensifying faster, then these storms making landfall could have a greater probability of being stronger storms," Niyogi told LiveScience.

The researchers also report that storms in the North Atlantic now typically mature from a Category 1 to a Category 3 in 40 hours instead of the 60 hours that transition took 25 years ago. (Hurricane Michael, currently swirling far out over the Atlantic went from a Category 1 hurricane to a Category 3 in about 6 hours, according to reports from the National Hurricane Center.)

The North Atlantic basin also shows the strongest warming trends during the study period. In the past 30 years, sea surface temperatures in Hurricane Alley – the main Atlantic hurricane development region – increased nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius).

The research is detailed in the May 26 issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Debating climate change

Scientists don't see eye-to-eye over global warming's effects on hurricanes. There are many environmental factors that could strengthen hurricanes or increase their frequency, including natural climate cycles. Researchers are actively investigating whether natural climatic variability is responsible for observed changes, such as an increase in hurricane frequency and strength in the Atlantic, while others are testing if climate change is the culprit. [10 Climate Change Myths Busted]

"There is legitimate uncertainty about a large number of issues about climate change and hurricanes. There are still pieces missing from the puzzle," said Michael Mann, a climate researcher and director of Pennsylvania State University's Earth System Science Center, who was not involved in the study.

Common criticisms of research connecting global warming and hurricanes include the fact that it often relies on data of different quality and collected with different techniques, or whose historical record is spotty. In addition, environmental variables beyond climate change are known to strengthen and weaken hurricanes.

To address these concerns, Niyogi and his co-authors studied wind-speed data from a uniform 25-year satellite record of storms across the planet. They also looked at only the primary intensification period – while the storms were still in open ocean water. During this first build-up, wind speeds change primarily due to oceanic feedback. This avoids the complicating influence of complex atmospheric processes such as wind shear (winds flowing in opposite directions at different heights in the atmosphere) and interaction with other storms, as well as travel over land, Niyogi explained.

"This study adds another piece to [the] puzzle and makes clear this picture that is emerging, that there will be an influence of climate change when it comes to the rate of intensification of storms and maximum intensity that storms can reach," Mann said. "There's this whole body of work that does seem to be pointing in the same direction of increasingly fast intensification and increasing intensity in the Atlantic."

Preventing Losses

Damage from hurricanes is a major issue in the United States. Losses from Hurricane Isaac, which flooded Louisiana and Mississippi in August and September, are estimated at $1.2 billion. And Isaac was a Category 1 hurricane.

But the risk of damage from stronger storms is outweighed by the expected financial hit from people putting themselves in harm's way, according to a study published in the Aug. 28 issue of Geophysical Research Letters.

Changes in exposure – more people living on the coast, more expensive real estate – are much more important than an increase in wind speeds when considering future financial losses, said study coauthor Rick Murnane, an expert in natural hazards at the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences in Garrett Park, Md.

But improving building codes can make a significant impact in reducing the economic impact of storms, Murnane added.

"If you build properly for wind speeds, these losses aren't going to matter," he said. "In Bermuda, houses are built to withstand 150 mph [240 kph] winds, so unless you have very strong hurricanes, relatively little damage is done to buildings. You can still have people living along the coast and be able to withstand these events with relatively small amounts of damage."

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.