New Swine Flu Virus Shows Lethal Signs

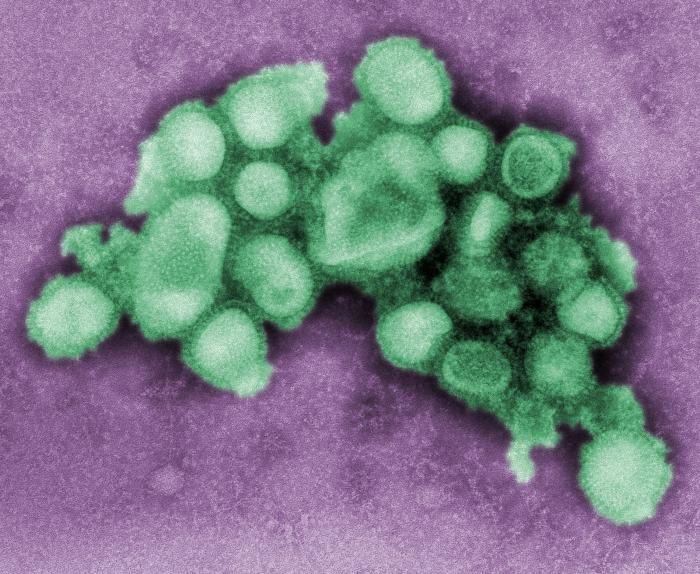

An influenza virus isolated from Korean pigs is deadly and transmissible by air in ferrets, which are used as stand-ins for humans when studying the disease.

This particular virus is likely not a grave threat to humans, said study researcher Richard Webby, a virologist at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn. However, the findings do highlight the need to understand more about the viruses circulating among pigs, Webby said.

"We've identified a couple of mutations that seem to be important for swine viruses and potentially increase their risk to humans," Webby told LiveScience. "The more of those type markers we can find, the better our surveillance and the more informative our surveillance can be." [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

Virulent flu

Pigs can be infected by swine flu, human flu and avian flu, making them a perfect mixing pot for different versions of the virus to swap genes and potentially become transmissible across species. In 2009, an outbreak of swine flu caused by the H1N1 virus led to a pandemic, killing between 151,700 and 575,400 people across the globe in a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About half of these deaths occurred in Southeast Asia and Africa.

Webby and his colleagues collaborated with Korean researchers to assess the public health risk from pigs there. They isolated swine flu viruses from swine abattoirs and infected ferrets with the viruses. Ferrets are used to test flu transmissibility because they're about as susceptible to the disease as humans and have similar immune responses and respiratory systems, Webby said.

Three of the viruses found in the dead swine caused disease, the researchers report online this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Only one, however, was highly lethal and transmissible by respiratory droplet, meaning that other ferrets could contract the disease just by contacting airborne fluids coughed or sneezed by an infected ferret.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This virulent strain, H1N2, caused classic flu symptoms in the ferrets, from sneezing and labored breathing to weight loss and high fever. All three ferrets inoculated with the disease died or were euthanized humanely within 10 days. Three more ferrets were exposed to the sick animals (before they died); two of them contracted the flu. One died, and the other had to be euthanized because its illness was so severe.

"This one particular virus was a little bit unexpected," Webby said. "It actually caused quite severe disease and actually transmitted quite freely."

Monitoring viruses

An investigation of the lethal H1N2 strain revealed changes in two proteins, HA225G and NA315N, which seemed linked to the increased virulence. The proteins are involved in binding the virus to its target cells and in releasing it from the cells, Webby said, suggesting that the changes have to do with how the virus interacts with the cells it infects.

H1N2 is a close cousin of the H1N1 pandemic virus, Webby said, meaning that people who have been vaccinated or exposed to that pathogen are likely safe from this one. That means that even if H1N2 develops the ability to jump to humans, it likely isn't a major threat.

Experiments that modified the H5N1 bird flu virus so it could spread, airborne, between ferrets, created a furor. We test your knowledge of these mutant flu viruses.

Mutant Bird Flu: Test Yourself

Nevertheless, "there are a number of threats in animal populations," Webby said. These include strains of H5N1, an avian flu virus that was recently the focus of controversy when scientists outlined the genetic changes necessary to make that strain transmissible between mammals. The findings triggered debate over whether such research should be released, given that terrorist groups or a rogue government could attempt to use the information to bioengineer a pandemic.

Scientists are currently pretty good at identifying and cataloguing the flu viruses that pop up naturally in domesticated animals, Webby said, but they lack a good way to judge whether a given virus has pandemic potential in humans. Sequencing viral genes and identifying changes linked to transmissibility and lethality will help fill in those blanks, Webby said.

"We have to keep vigilant about viruses that are circulating in [the pig] population," he said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.