NASA's Mars rover Curiosity is on the verge of passing a rigorous month-long health checkup with flying colors, scientists announced today (Sept. 12).

Since Curiosity landed inside Mars' Gale Crater on Aug. 5, researchers have been systematically checking out the rover's systems and its 10 science instruments to make sure they're all in good working condition. Those inspections have gone very well and should be finished by the end of Curiosity's next Martian day, or sol, mission team members said today.

"The success so far of these activities has been outstanding," said Curiosity mission manager Jennifer Trosper, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Throughout every phase of the checkouts, Curiosity has performed almost flawlessly."

And this commissioning phase of Curiosity's two-year mission has proceeded pretty much exactly on schedule, Trosper added. [11 Amazing Things Curiosity Can Do]

"Our estimate for the checkout activities was 25 sols, and it's taken us 26," Trosper told reporters today, explaining that a 12-sol stretch of driving activities brings Curiosity to its current Sol 37 on Mars. "So, not bad."

Getting ready to drive again

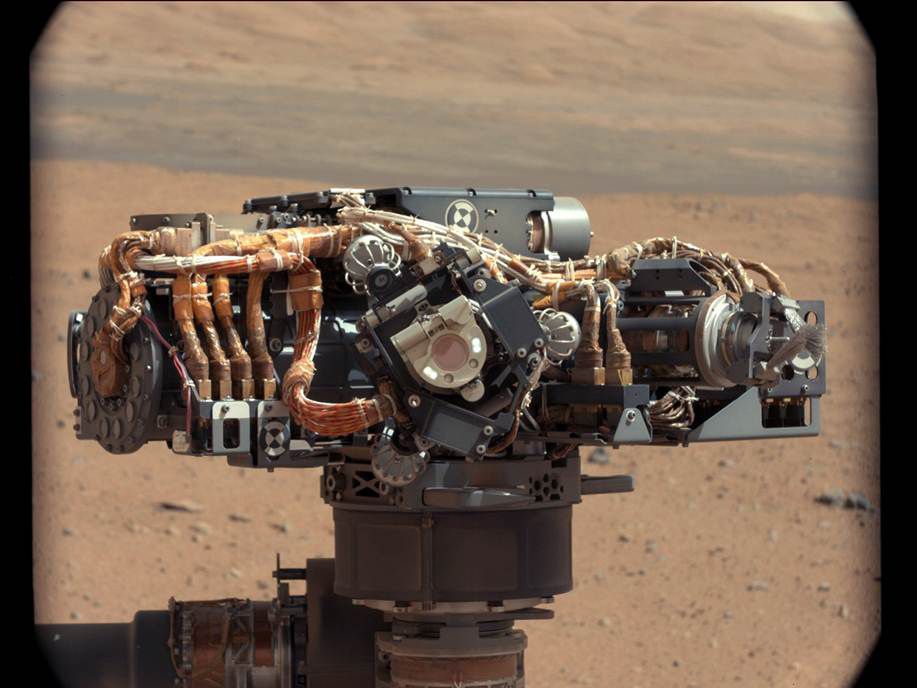

Curiosity has spent the last six sols methodically testing out its 7-foot-long (2.1 meters) robotic arm, which bears several tools on its end, including a rock-boring drill and a camera called the Mars Hand Lens Imager, or MAHLI.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

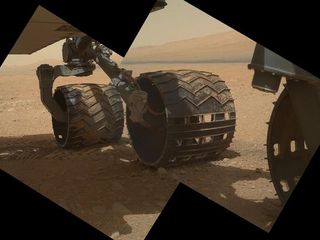

One more sol of arm checkouts remains, Trosper said. The team also plans to point Curiosity's Mast Camera (Mastcam) toward the sky today, to watch the Martian moon Phobos cross the face of the sun. Then the $2.5 billion robot will be ready to move its six wheels again for the first time in more than a week.

"After that, starting on Friday evening, the plan is to drive, drive, drive," Trosper said.

Curiosity will stop when it finds a rock scientists deem a suitable target for observations with MAHLI and the rover's Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer instrument (APXS), which also sits on the robotic arm's turret, Trosper said.

APXS measures the abundance of chemical elements in rock and soil by exposing the material to X-rays and alpha particles (helium nuclei, consisting of two protons and two neutrons).

Searching for habitable environments

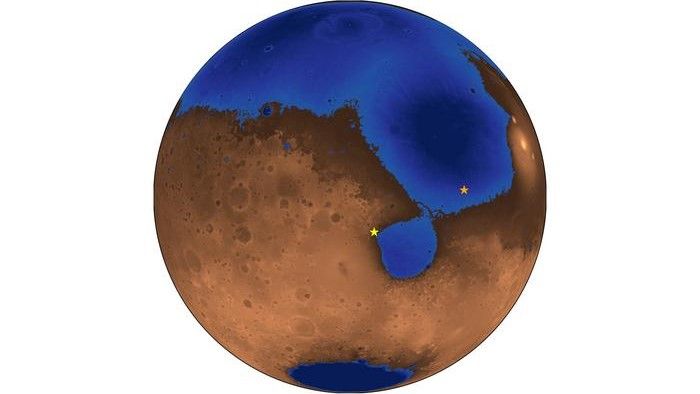

Curiosity's chief task is to determine if the Gale Crater area has ever been capable of supporting microbial life. The rover's primary science target is the base of Mount Sharp — a mysterious 3.4-mile-high (5.5 km) mountain rising from Gale's center — where Mars-orbiting spacecraft have spotted signs of long-ago exposure to liquid water.

But Curiosity isn't headed yet to Mount Sharp's foothills, which lie about 6 miles (10 km) away. It's on its way first to a spot called Glenelg, where three different types of terrain come together in one place.

Glenelg sits about 1,300 feet (400 m) from Curiosity's landing site. So far, the rover has driven 269 feet (82 m) as the crow flies on the trek to Glenelg. While the mission team eventually wants Curiosity to go about 330 feet (100 m) in a big driving day, at present they're only willing to push it about 131 feet (40 m) or so per sol, Trosper said.

After Curiosity studies the rock with MAHLI and APXS, it will find a sandy area to do its first soil scooping. The rover will deposit dirt into the analytical instruments on its body, the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument (SAM) and the Chemistry and Mineralogy tool, or CheMin.

Then the rover will test out its drill for the first time. That will be an exciting moment for the team, for the drill allows Curiosity to bore 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) into rock — deeper than any other Mars robot has been able to go.

Drilling isn't quite imminent, however, since Curiosity has several big tasks to check off first.

"It's on the order of a month-type timeframe for drilling," Trosper said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.