The Underappreciated "Smaller Majority" that Dominate Marine Ecosystems

This ScienceLives article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Marine ecologist Paul C. Sikkel calls smaller marine organisms such as parasites “the smaller majority,” because they account for large percentages of the members of coral reef communities without receiving due recognition for their ecological importance. Despite the generally underappreciated status of relatively small reef residents, the discovery by Sikkel’s research team of a new coral reef parasite — which Sikkel named Gnathia marleyi after Bob Marley — garnered coverage by dozens of major media outlets all over the world. For more information about Bob Marley’s new namesake, see this press release.

Sikkel — who runs a marine laboratory at Arkansas State University — studies host-parasite-cleaner interactions on coral reefs, and the influences of changes in reef ecology triggered by climate change.

Sikkel has involved undergraduates in coral reef research and taught field courses in marine ecology for the past 15 years. His lively, creative teaching style (which incorporates Jimmy Buffett’s music) is profiled in an article and slide show.

In addition to leading research projects and teaching, Sikkel passionately communicates the science of the sea to the public. His work has appeared in popular outlets such as Natural History and National Geographic, the award-winning film Seasons in the Sea, and the television series National Geographic: Wild Chronicles. More information about Sikkel’s outreach activities is posted on his website.

What inspired you to choose this field of study?

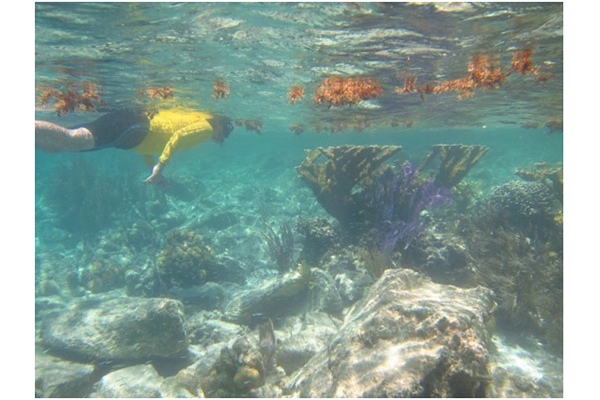

Like so many other marine scientists, I grew up watching Jacques Cousteau on TV. Once I started snorkeling in seventh grade: that was it! I was hooked.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is the best piece of advice you ever received?

Find what stokes you and go for it! (That advice is courtesy of Dr. Mark Hixon, my doctoral advisor).

What was your first scientific experiment as a child?

I’m not sure it really counts as an experiment per se, but I used to spend hours watching animals in nature (birds, lizards, fish — you name it) and writing down what they were doing and wondering why they were doing it.

What is your favorite thing about being a researcher?

Being in the field and seeing things few people ever see! The thrill of discovery and being an insider to nature’s secrets! Being on a coral reef at dawn!

What is the most important characteristic a researcher must demonstrate in order to be an effective researcher?

Curiosity, imagination, creativity, patience and persistence.

What are the societal benefits of your research?

I now work on what I call “the smaller majority” — the tiny organisms, such as parasites, that really run natural systems but rarely get the headlines. Understanding these organisms is essential to understanding how ecosystems work. I also use my research as a teaching tool for students ranging from K-grad.

Who has had the most influence on your thinking as a researcher?

Wow! Tough question. I have been influenced by so many people, not all of them scientists.

But some of my early mentors were:

- Jack Bradbury: Behavioral Ecologist, U.C. San Diego. Now retired. He was a topnotch and very passionate field biologist.

- Peter Klimley: Shark biologist. Currently at the University of California, Davis. He was a Ph.D. student at Scripps when I was an undergrad at University of California, San Diego. He gave me my first research opportunity, working on hammerhead sharks in the Gulf of California. I worked with him for four years.

- Dory Fragaszy: Her full name is "Dorothy." She studied primate behavior at San Diego State University where I started my undergraduate work before transferring to University of California, San Diego. She was my mentor there and I took several classes from her. She is now at the University of Georgia.

Later, my mentors included:

- Mark Hixon: Mark was my Ph.D. advisor at Oregon State University where he is currently a professor of marine ecology. He was the perfect advisor for me and I continue to collaborate with him.

- Bob Warner: Bob Warner recently retired from University of California, Santa Barbara. He is arguably the best marine fish behavioral ecologist ever. He and Mark were the ones who advised and encouraged me most during my Ph.D. work. Bob was on my doctoral committee.

- Don Kramer: Don Kramer was my postdoctoral mentor at McGill University during my research at the McGill marine lab (Bellairs) in Barbados. I think Don is the most eclectic and creative person I have worked with.

- E.O. Wilson: Wilson biologist, researcher theorist, naturalist, and author who is generally considered to be the world’s foremost authority on ants. He was the Joseph Pellegrino University Research Professor in Entomology at Harvard University, and a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction.

I do not "know" Wilson but have met him twice, once in Barbados and once in Louisville, Kentucky. I use his books in my introductory classes because he is a master at bringing the thrill of discovery in biological science to the lay person, is a strong conservationist, and truly appreciates the intimate link between the arts and sciences. If I could have coffee with anyone in the world, it would be with E.O. Wilson.

What about being a researcher do you think would surprise people the most?

There’s a lot of art and intuition involved. It’s also very hard work — people who do research, including those who work with me — know that, but most people don’t realize just how hard we work. But, it’s also great fun — in fact, it’s an addiction.

If you could only rescue one thing from your burning office or lab, what would it be?

Well, besides my portable hard drive and pictures of my kids, probably my Bob Marley paraphernalia and my signed copies of E.O. Wilson books.

What music do you play most often in your lab or car?

My musical staples include Bob Marley (I also enjoy the music of Bob Marley’s oldest son — Ziggy Marley).

It is important to note that my naming the species after Bob Marley has nothing to do with the fact that this species is a parasite and everything to do with the fact that I think it is a really cool organism and I am a huge Marley fan!

I am also a big fan Jimmy Buffett, Neil Young and the Grateful Dead and Jimmy Buffett: I still get the chills every time I listen to his live version of A Pirate Looks at 40, which blends into Bob Marley’s Redemption Song!

Another favorite of mine is Santana. So I was particularly thrilled when a friend of mine recently told me that he heard Carlos Santana mention during one of his recent concerts that a newly discovered species had been named after Bob Marley!

Editor's Note: The researchers depicted in ScienceLives articles have been supported by the National Science Foundation, the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the ScienceLives archive.