One Red Cent: Curiosity Rover Totes Penny on Mars

Coin collectors may have a new unattainable object to dream about — a six-wheeled robot's lucky penny on Mars.

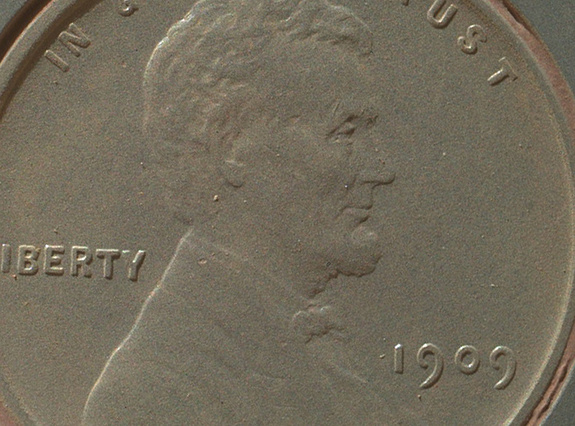

NASA’s Mars rover Curiosity is carrying a 1909 "VDB" Lincoln Cent, for use as a calibration target for the robot's Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) instrument. A close-up image of the penny has shown that Lincoln’s face got blasted a bit by particles on the night of Aug. 5, when the 1-ton rover touched down.

The penny was facing directly toward the plume of dust churned up by the engines of Curiosity's sky crane descent stage, which lowered the rover to the Martian surface on cables.

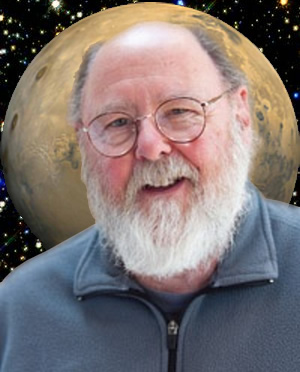

"A penny for your thoughts," I asked MAHLI principal investigator Ken Edgett, senior research scientist at Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego. He said that Curiosity was going to launch in 2009, the centennial of the Lincoln Cent and bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth. [Curiosity Rover's Mission: Complete Coverage]

"When the launch was delayed, I made a decision to stick with the historic 1909 cent rather than try to find a 1911 cent," Edgett told SPACE.com. "Honestly, I think 1911 would have been more difficult to explain."

Edgett said that it might have been fun to fly a 2011 or 2012 cent, "but they did not exist when the calibration target was assembled and delivered."

Nod to geologists

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Lincoln Cent was designed by Victor D. Brenner to honor the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s 1809 birth. The designer’s initials (V.D.B.) appear near the bottom of the coin on the reverse of a limited number of coins from 1909.

Brenner based the coin’s low-relief portrait of Lincoln on a photograph taken Feb. 9, 1864, by Anthony Berger in the Washington, D.C. studio of famed photographer Mathew Brady.

According to a press statement from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which manages Curiosity's mission, the penny is also a nod to geologists’ tradition of placing a coin or other object of known size as a reference in close-up photographs of rocks. The penny also gives the public a familiar object for perceiving size easily when it will be viewed by MAHLI on Mars.

Curiosity's new image of the Lincoln Cent was acquired with MAHLI at a distance of 2 inches (5 centimeters). MAHLI can acquire photos of even higher resolution and can be positioned as close as 1 inch (2.5 cm).

However, the first checkout test of Curiosity’s robotic arm did not call for placing MAHLI at its closest focus distance, researchers said.

Sky’s the limit

"Now this is interesting!" Dan Harris of CoinStudy.com told SPACE.com. Space-flown objects with attribution and certification by astronauts and/or NASA officials are very valuable, he added.

What if a daring, space-suited numismatist made his or her way to Mars, tracked Curiosity down, pried off the penny and returned to Earth with the coin? How much would it be worth?

"A 1909 Lincoln penny is well known and valuable to coin collectors. There are also many collectors of space memorabilia," Harris said. "Combine the two vying for a 1909 penny returning from Mars, a 'one of a kind,' and it would be…my opinion…the sky is the limit!"

The penny is now a historical artifact, however, and it's also government property. So you'd probably have difficulty cashing in.

Joe the Martian

The Lincoln penny isn't MAHLI's only calibration target. The instrument also uses a "Joe the Martian" character, color references, a metric bar graphic and a stair-step pattern for depth calibration.

Joe the Martian appeared regularly in a children’s science periodical called "Red Planet Connection" in the 1990s, when Edgett directed the Mars outreach program at Arizona State University.

But Edgett created Joe the Martian earlier, as part of his schoolwork when he was 9 years old and at a time when NASA’s Viking missions, which launched in 1975, were inspiring him to become a Mars researcher.

The $2.5 billion (and 1 cent) Curiosity rover is about six weeks into a planned two-year mission on the Red Planet. Its main goal is to determine whether or not Mars could ever have supported microbial life.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is a winner of last year's National Space Club Press Award and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years.