Life After Traumatic Injury: How the Body Responds

The leading cause of death in people between the ages of 1 and 44 in the United States isn't heart disease or cancer — it's injury from falls, car accidents and other types of physical trauma.

While research has led to significant improvements in survival immediately after a traumatic injury, challenges remain. To help address them, scientists funded by the National Institutes of Health are focusing on understanding what happens to the body at many levels, from its molecules and cells to its tissues, organs and systems.

Organ Disorder

Some survivors of severe injury can lose organ function, generally starting with the lungs and kidneys and then moving to the liver and intestines. This potentially deadly condition, called multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), can happen early if people go into shock, when their tissues don't receive adequate oxygen. It can also occur later in the recovery process.

Doctors only started to notice MODS as a complication of trauma in the 1970s, when intensive care units improved procedures for treating shock. Advances in blood transfusion, fluid drainage and intravenous medicine delivery kept patients alive, but didn't effectively prevent their organs from shutting down later.

Researchers noticed that MODS was associated with infections — particularly in people who experienced abdominal trauma — leading them to believe that bacteria or viruses were the cause for ongoing organ injury. But not every case of MODS is linked to an infectious agent.

To examine the relationship between infection and organ dysfunction, researchers led by Ronald Tompkins of Massachusetts General Hospital collected data for 7 years on over 1,600 people who had been hospitalized for trauma. Of those study participants who survived the first 48 hours, 29 percent still experienced MODS during their hospitalization.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on diagnostic data about infections and the degree of organ dysfunction, the researchers determined that MODS mainly happened before infections, and not the other way around. These findings contribute to a shift away from existing assumptions about the cause of MODS and could point to ways of treating or preventing this serious complication.

Genomic Storm

It's not just organs that can behave differently after trauma; genes can, too. A nationwide team headed by Tompkins conducted a 10-year study of hospital patients whose conditions included severe blunt trauma. The researchers determined that all the blunt trauma cases requiring intensive care incited a "genomic storm" in which 80 percent of the genes controlling immune activity behaved differently in the first four weeks following the injury than they did in a healthy individual.

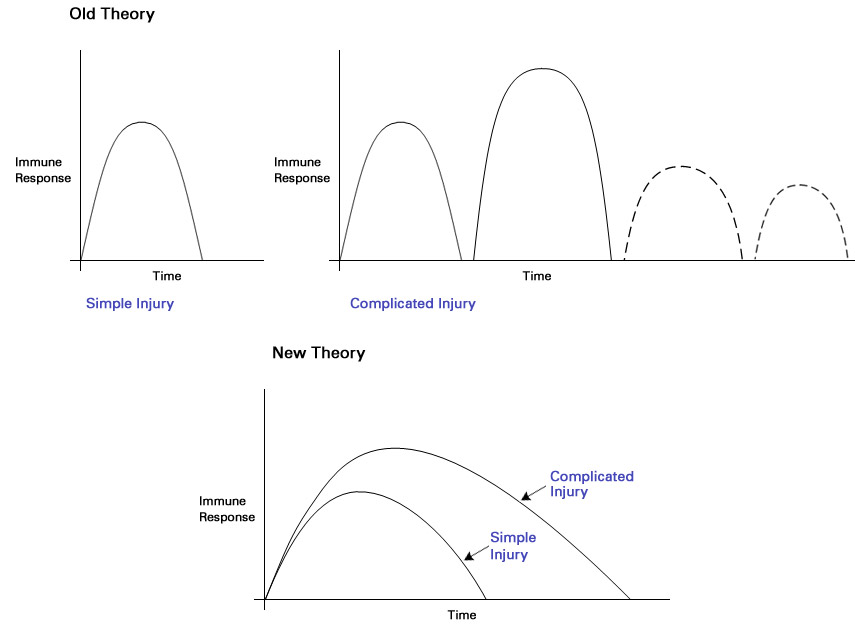

This result was surprising because the existing theory was that people who heal quickly from a severe injury have a single surge of gene activity and immune response, while people who take longer to recover (and often experience complications) have multiple surges.

In this study, the researchers found that the activity of the same genes was disrupted in all patients, regardless of whether they had quick recoveries, slower recoveries with complications, or they died. The only difference was that the people with longer healing periods had a more powerful and longer-lasting gene response that could lead to MODS and other major problems.

Sepsis and Cognitive Function

Another potential result of trauma is body-wide inflammation, or sepsis. Following a traumatic injury, the body produces a flood of white blood cells that can secrete a protein called HMGB1. This protein contributes to septic inflammation, which can be life-threatening.

Up to 25 percent of people who survive sepsis experience physical or cognitive impairment. Kevin Tracey, a neurosurgeon at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, who has spent decades researching ways to prevent death from sepsis, suspected that HMGB1 could play a role in this process as well as in general inflammation.

Studying mice with sepsis, Tracey and his colleagues found that, even when symptoms of sepsis subsided, the survivors had HMGB1 in their systems for at least four weeks, and many of them experienced a decline in cognitive function. When the mice were given a drug to block HMGB1, their ability to remember improved. This finding could pave the way for a treatment to address cognitive impairment in human sepsis survivors.

Standards Save Lives

To study trauma cases in a systematic and consistent way at a number of hospitals across the country, the Tompkins team had to develop standards of practice for all to follow. Not only did this standardization help the scientists conduct a better-controlled study, but it also saved lives.

Over the course of six years, trauma centers involved in the research saw a drop in deaths among study participants. During the first two years of the study, 22 percent of patients died within 4 weeks of being admitted to the trauma centers. During the last two years, that rate was cut in half. The scientists attribute the trend to an increase in compliance with the standard operating procedures over the period.

These projects and others contribute to a shift in focus among researchers and medical professionals — from keeping people alive immediately after a traumatic injury to improving life after survival.

This Inside Life Science article was provided to LiveScience in cooperation with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Learn more:

- Fact Sheets on Sepsis and Trauma

- Video: The Body’s Response to Traumatic Injury

Also in this series: