Winds High In Sky Affect Deep-Ocean Currents

Periodic changes in the strong winds that whip around the Arctic, 15 to 30 miles (24 to 48 kilometers) above the ground, influence currents deep within the ocean and affect the global climate, according to a new study published yesterday (Sept. 23) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

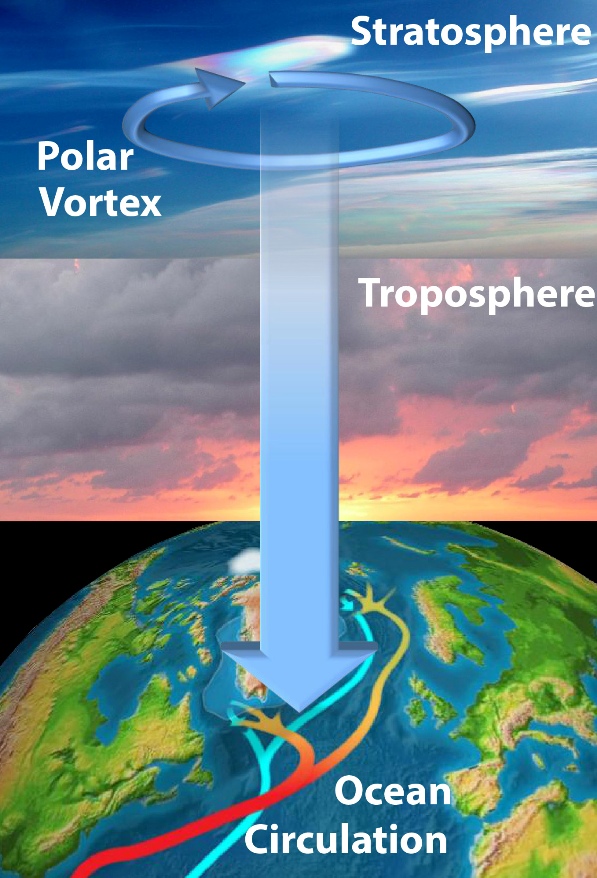

It was already known that processes in the stratosphere, which begins 6 miles (10 km) above Earth's surface, affect the troposphere, the atmospheric layer just above the surface where weather occurs (and in which we live in). Weather, in turn, influences ocean currents. But the new study is one of the first to show a strong link between the stratosphere and the deep ocean, according to a release from the University of Utah.

"Now we actually demonstrated an entire link between the stratosphere, the troposphere and the ocean," Thomas Reichler, University of Utah researcher and study author, said in the statement.

Reichler's team used weather observations and 4,000 years' worth of supercomputer simulations of climate conditions to show that high-altitude Arctic winds affect the speed of the Gulf Stream, the ocean current that transports warm surface waters from lower latitudes into the North Atlantic, where they cool, sink and return south. This "conveyor belt" affects the whole world's ocean circulation and climate.

But the conveyor belt has a weak spot in the North Atlantic, south of Greenland, where sinking or "down-welling" occurs. This area "is quite susceptible to cooling or warming from the troposphere," Reichler said. If the water is close to becoming heavy enough to sink, then even small additional amounts of heating or cooling from the atmosphere can speed or slow this process, he said.

Changes in the high-altitude winds above the Arctic, called the polar vortex, have a strong effect in this small region. Because of that sensitivity, Reichler calls the ocean south of Greenland "the Achilles heel of the North Atlantic."

These winds whirl counterclockwise around the North Pole at up to 80 mph (130 kph). But about every two years, this circulation system is weakened by sudden warming, and sometimes even shifts direction to run clockwise. This lasts for up to 60 days, during which time the shifting winds propagate down through the atmosphere to the ocean, speeding or slowing the Gulf Stream. [Weirdo Weather: 7 Rare Weather Events]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study adds another wrinkle to scientists' conception of global climate, revealing how the system is vulnerable to unexpected and regional changes.

"If we as humans modify the stratosphere, it may — through the chain of events we demonstrate in this study — also impact the ocean circulation," Reichler said.

Reach Douglas Main at dmain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @Douglas_Main. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.