Pint-Sized Primates Were First in North America

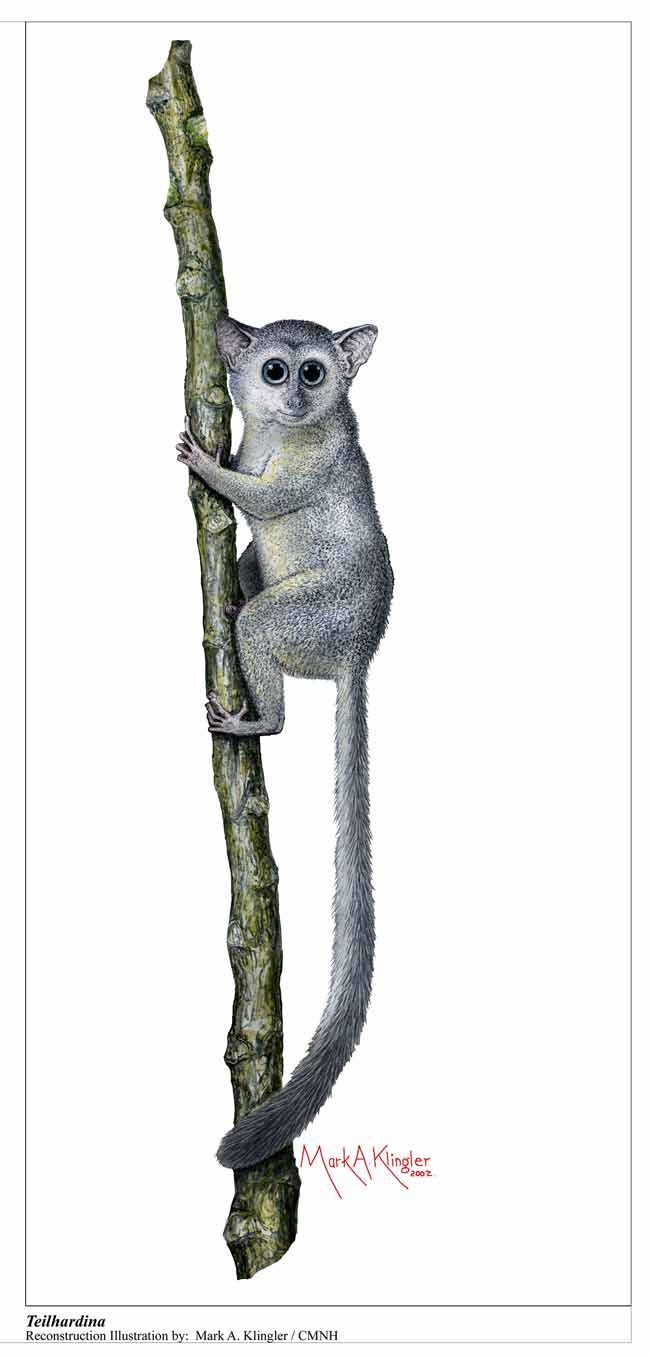

Leaping, furry mini-monkeys that were as small as mice crossed the Bering land bridge long before humans, representing North America's oldest known primates.

This new claim is based on the fossils of at least three individuals of this previously unknown species of extinct primate uncovered at a site near Meridian, Miss., scientists announced today. The researcher estimates the primate fossils date to about 55.8 million years ago.

If the age of the fossils is accurate, the new finding could indicate that early primates migrated across the land bridge that once connected Siberia with Alaska long before Homo sapiens that arrived some 12,000 to 14,000 years ago. The teeny primate crossover from Asia happened during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum when global temperatures rose at a rate and magnitude similar to today's global warming.

"The primate itself appears new to science, and is thus a welcome addition to what is still a small 'Red Hot' fauna in Mississippi," said Philip Gingerich of the Museum of Paleontology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who wasn't involved in the recent discovery. "The site has the potential to be important, but the importance depends to some extent on whether it is really the age the author claims or not."

Called Teilhardina magnoliana, the mini monkey-like creature weighed just an ounce (28 grams) and would have leapt across treetops to snatch up insects and fruits.

"They were acrobatic little creatures," said K. Christopher Beard of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, who details his finding in the March 4 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Monkey map

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Closely related species of Teilhardina have been found at sites in China, Belgium, France and Wyoming.

The fossil evidence from the international sites indicates Teilhardina inhabited North America, Europe and Asia at roughly the same time. Researchers have puzzled over the sequence of colonization, or how these tiny primates spread over much of the globe at a time when global climate and sea levels were changing rapidly.

Before the fossils were found in Mississippi, scientists thought Teilhardina migrated from Asia to Western Europe before moving on to North America.

To date the Mississippi fossils, Beard took advantage of the idea that sea level remains constant across the globe at any given time. By matching up erosion features caused by a falling sea level over long distances, Beard estimated the Mississippi fossils are older than Teilhardina fossils from Belgium and France. That suggests the primates moved from Asia to North America and then to Western Europe.

The standard for dating fossils, however, relies on carbon isotopes, Gingerich said.

The study "inexplicably contains none of the now-standard evidence of carbon isotope values that define both the Paleocene-Eocene boundary and the carbon isotope excursion," Gingerich said. "Without this, it is really not possible to know how old the new primate from the 'Red Hot' site is or what it means for mammalian biogeography."

Beach bums

The coastlines of North America afforded certain advantages to the small primates. For instance, during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, the coastlines became hot and wet, while the Rocky Mountain region became hot and dry. The dry conditions would not have supported the lush trees and their yummy fruits required for Teilhardina and other closely related primates.

Beard found that Teilhardina magnoliana from Mississippi is both older and more primitive than another Teilhardina species previously found in Wyoming's Bighorn Basin. Since the fossil record at Bighorn is remarkably complete, Beard is confident that fossils older than those unearthed in Mississippi would have been found by now if they existed.

That means the earliest North American primates were restricted to coastal regions for thousands of years before they were able to colonize the Rocky Mountain region.

Later, precipitation would have increased to make Wyoming and other Rocky Mountain regions hospitable to the little primates.

Chill out

Though Teilhardina once occupied parts of the United States for tens of thousands of years, none of its distant relatives, such as monkeys, currently live here.

That's because most primates are adapted to live only in wet, humid tropical or subtropical regions. When Earth began cooling at the end of the Eocene about 35 million years ago, Teilhardina vanished from North America and Europe, Beard said.

Modern humans obviously are adapted to live in a variety of climates today, but at that time, warmer regions were critical layover spots for our primate ancestors. Lucky for us, Beard says, some of these ancestors in the late Eocene had set up camp in warmer climes.

"You and I wouldn't be here talking about it if it weren't for the fact that primates by this time were able to colonize Central Africa and Southeast Asia," Beard told LiveScience. "As far as we know, those were the only two places that primates were able to survive this dramatic cooling event 35 million years ago."

- Top 10 Missing Links

- Why Haven't All Primates Evolved into Humans?

- Top 10 Amazing Animal Abilities

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.