Vampire Squid Are Sea's Garbage Disposals

Despite their name, vampire squid are not deep-sea bloodsuckers. In fact, new research finds these mysterious creatures are garbage disposals of the ocean.

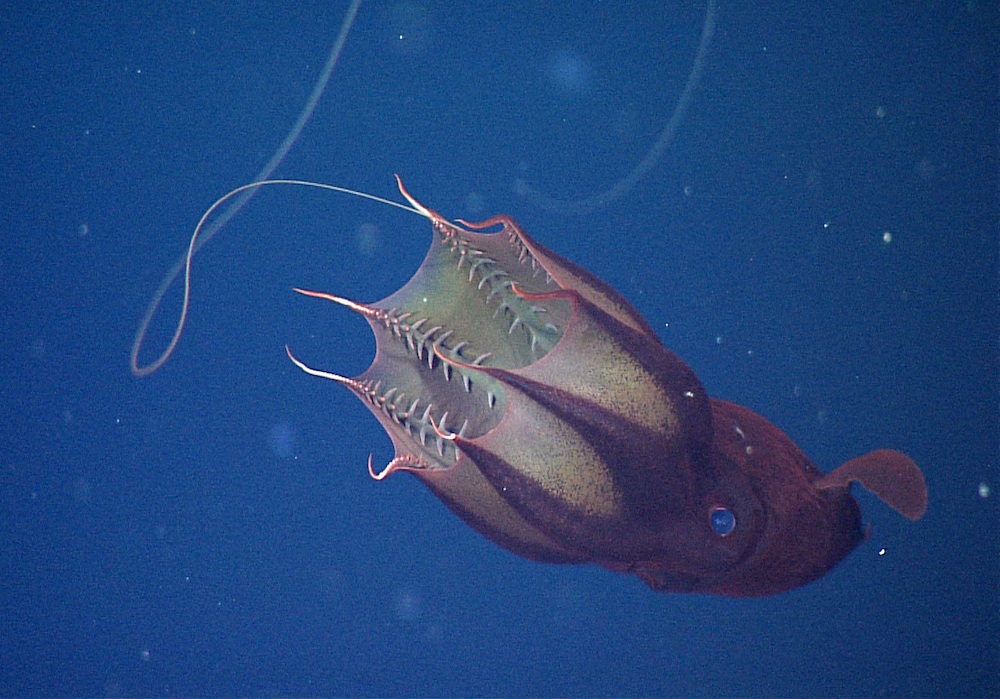

Using long, skinny tendrils called filaments, vampire squid capture marine detritus hovering in the water ― from crustacean eyes and legs to larvae poop ― then coat it in mucus before chowing down, according to the new findings.

The discovery is a first for cephalopods, which include squid, octopus and cuttlefish, said study researcher Henk-Jan Hoving.

"It's the first record of a cephalopod that doesn't hunt for living prey," Hoving, a postdoctoral scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California, told LiveScience. [Gallery: Elusive Vampire Squid]

A mystery squid

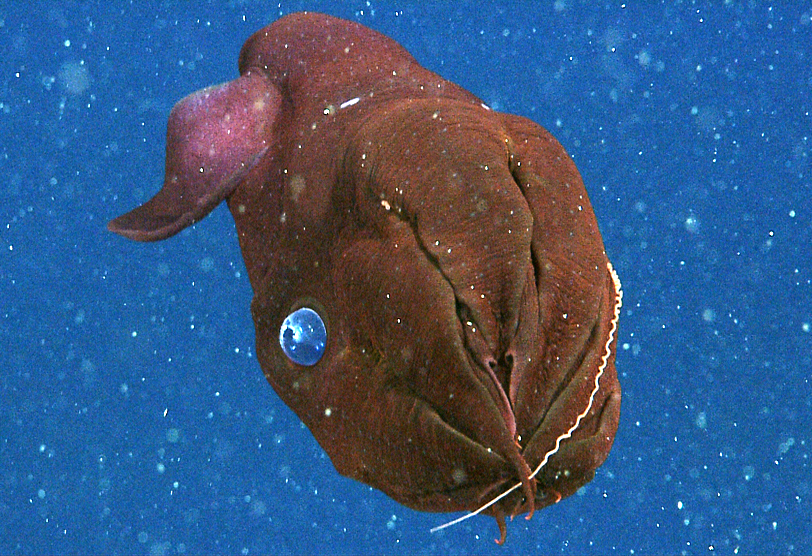

Vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis), which grow to be about a foot (30 centimeters) long, are widespread but not well-known. Even their life spans remains a mystery. Their name comes from their dark coloring, red eyes and the cloak-like webbing between their arms. And as namesakes of the undead, vampire squid apparently have little need for breathing. They thrive in oceanic oxygen minimum zones, where the oxygen levels are sometimes less than 5 percent that of the surrounding air.

Adding to their mystique, vampire squid are capable of bioluminescence. They use this self-made light to blend in with sunlight filtering down to the deep sea.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Along with their eight arms, vampire squid have two long, whiplike filaments. Researchers have long suspected that these long tendrils might help the squid feed, but the new study is the first to clarify how. [Under the Sea: A Squid Album]

Hoving and his colleagues observed captured vampire squid in the lab and also pored over 24 hours of videotape of vampire squid seen between 1992 and 2012 in their natural environments in Monterey Bay submarine canyon off the coast of Northern California.

Hoving said he first noticed that after researchers added some food to a tank containing a captive vampire squid, the animal retracted its filament and wiped it off on its suckered arms. And in the videos, Hoving noticed vampire squid with "amorphous masses" in their mouths.

After Hoving examined the digestive tract contents of museum specimens of squid, he began to put the pieces together. Instead of containing chewed-up fish or crustaceans as the stomachs of most cephalopods do, the vampire squid stomachs held bits of flotsam and jetsam: fish eggs, bits of crustacean antennae and eyes and legs, larvae and even larvae feces, among other things. These scraps were cemented together by chunks of mucus.

Vampire feeding strategy

An anatomical examination of the squid revealed their suckers have no suction power; rather, they excrete mucus. What appears to happen, Hoving said, is that squid hover in the water, extending out a filament (which can be up to eight times as long as their own body). Such behavior was seen in 33 percent of video observations.

Marine detritus, including bits of dead crustaceans, larvae, eggs and even tiny jellyfish-like creatures called salps, fall and float past the filament, getting caught on sticky hairs on the structure. The squid can then pull in the food and brush it onto their arms, which coat the food with mucus to stick it together. Finger-like appendages called cirri then move the food toward the mouth at the base of the arms. [10 Scariest Sea Creatures]

This passive eating style enables the squid to live in low-oxygen zones in the ocean, Hoving said. Vampire squid also have extremely low metabolisms and a specialized protein in their respiratory system that clings strongly to oxygen molecules, he said.

With this knowledge, Hoving said, researchers can study how fast the squid grow and how long they live.

"It shows again that cephalopods are extremely adapted in a wide variety of ways to the ocean habitat," Hoving said. "They're very successful in the world's oceans. It's amazing that some of these cephalopods have even found ways to live under conditions that are adverse to most other animals."

The researchers reported their findings today (Sept. 25) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.