Scientists Reveal Vampire Squid's Strange Eating Habits

(ISNS) -- The sinisterly named vampire squid dwells in water far too harsh for any of its relatives. Now scientists find it survives there by feeding on unliving matter instead of live prey, unlike any known living squid or octopus.

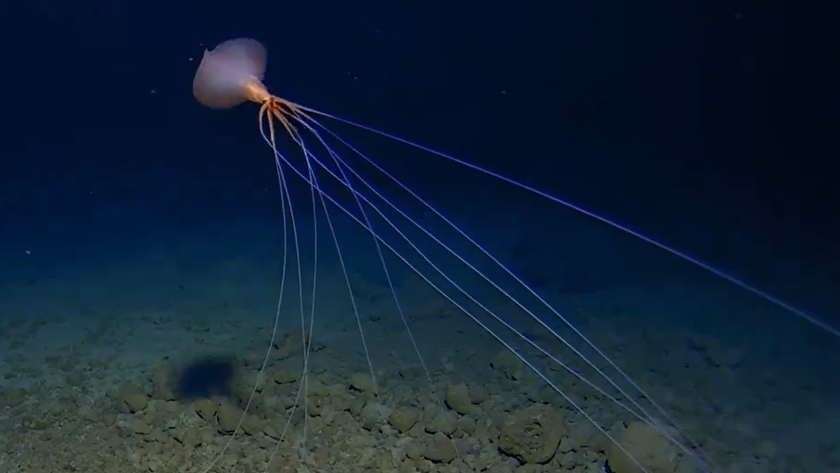

The creature's scientific name Vampyroteuthis infernalis, which means "vampire squid from hell," was awarded for skin that can look black, eyes that can appear red, and cape-like webbing between its arms. It has a relatively small body reaching up to 5 inches long, which has a gelatinous consistency similar to a jellyfish.

The name "vampire squid" is actually a misnomer. Although Vampyroteuthis is a cephalopod just as squid, octopuses, cuttlefish and nautiloids are, it is the only known living member of a distinct order of animals. Like octopuses, it has eight arms; like squid, it has two extra limbs, but while squid possess a pair of feeding tentacles used to catch prey, Vampyroteuthis has two retractable filaments up to eight times the length of its body that have puzzled researchers for years.

Vampyroteuthis lurks in temperate and tropical oceans around the world in waters far too low in oxygen for octopuses and squid. To learn more about how Vampyroteuthis can survive in such harsh conditions, scientists watched vampire squid in their natural habitat for 20 years, using deep-sea remotely operated subs in Monterey Bay in California that delved into the oxygen-poor waters where the vampire squid dwell, between 2,000 and 3,000 feet below the surface. The researchers also conducted feeding experiments with live specimens they collected and dissected others to investigate the squid's anatomy under a microscope.

The researchers found that Vampyroteuthis apparently dines on "marine snow" -- surprisingly nutritious animal remains, plankton and excrement that rains down from above.

"It has a completely different way of feeding than any other cephalopod known to date," said researcher Henk-Jan Hoving, a marine biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California. "All squid and octopods hunt for their prey. This vampire squid eats dead material."

The scientists typically saw lone Vampyroteuthis hovering motionless in the water with a single filament extended outward. Its filaments are loaded with sensory cells that make the animal very sensitive to any detritus that drifts by. Its large, highly developed eyes are very keen to dim light, helping to spot potential morsels.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The filaments are covered in short stiff hairs that can snag onto marine snow. When a large enough meal accumulates on a filament, Vampyroteuthis uses its arms to collect this detritus from the filament, wraps it up in mucus it secretes from its suckers, and pops the clump into its mouth.

"It's a very strange cephalopod in many ways, and the fact that its feeding behavior is very unusual goes along with that," said cephalopod specialist Michael Vecchione at the Smithsonian Institution, who did not take part in this study.

The relatively weak mouth muscles Vampyroteuthis sports reinforce the notion that it goes after dead matter and not the living. This low-key, passive lifestyle is probably vital to surviving in its oxygen-starved home; indeed, Vampyroteuthis has the lowest metabolic rate known for any cephalopod.

"The next thing we want to find out is how old vampire squid get and how fast they grow, given their extremely low metabolisms," Hoving said. He and his colleagues detail their findings online Sept. 26 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Vecchione noted that researchers should also investigate vampire squid in other parts of the world. "It'd be interesting to see if they depend on a heavy rain of marine snow as well, or whether they feed more on things like jellies," he said.

Charles Q. Choi is a freelance science writer based in New York City who has written for The New York Times, Scientific American, Wired, Science, Nature, and many other news outlets.

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics.