Son's DNA Shows Up in Mom's Brain

A mother may always have her children on her mind, literally. New findings reveal that cells from fetuses can migrate into the brains of their mothers, researchers say.

It remains uncertain whether these cells might be helpful or harmful to mothers, or possibly both, scientists added.

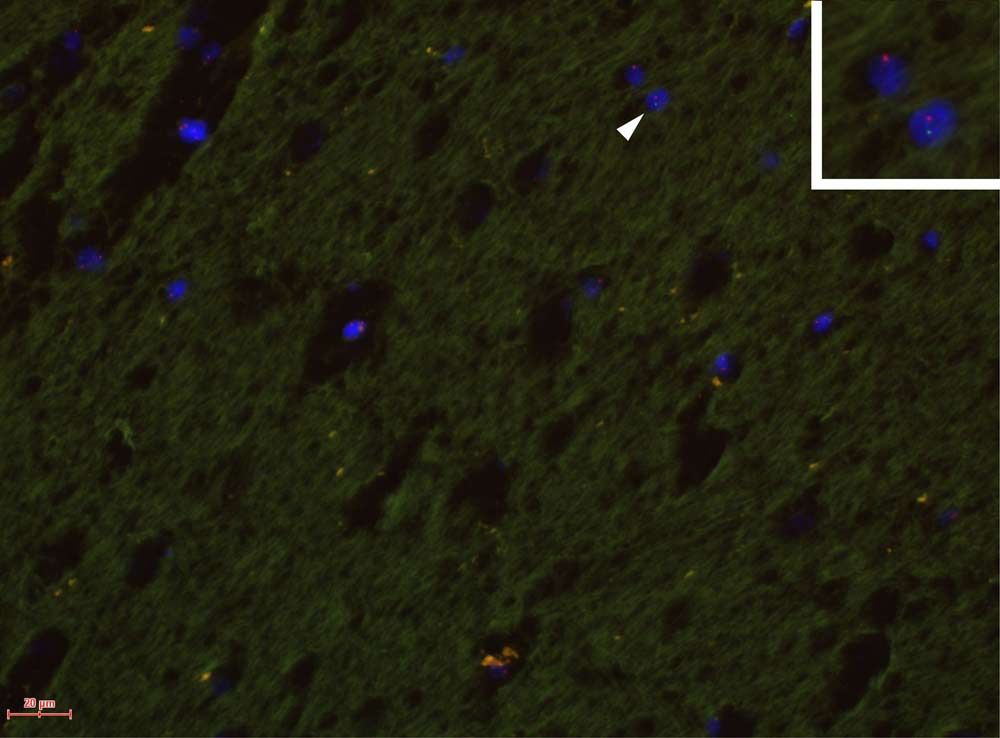

Recent findings showed that during pregnancy, mothers and fetuses often exchange cells that can apparently survive in bodies for years, a phenomenon known as microchimerism. Scientists had found that in mice, fetal cells could even migrate into the brains of mothers. Now researchers have the first evidence fetal cells do so in humans as well.

The investigators analyzed the brains of 59 women who had died between the ages of 32 and 101. They looked for signs of male DNA ―which, they reasoned, would have come from the cells of sons. (They searched for male DNA because female DNA would have been harder to distinguish from a mother's genes.)

Nearly two-thirds of the women — 37 of the 59 — were found to have traces of the male Y chromosome in multiple regions of their brains. This effect was apparently long-lasting: The oldest female in whom male fetal DNA was detected was 94.

The defense system known as the blood-brain barrier keeps many drugs and germs in the bloodstream from entering the brain. However, doctors have found this barrier becomes more permeable during pregnancy, which could explain how these fetal cells migrated into the brains of their mothers. [8 Odd Body Changes That Happen During Pregnancy]

Although 26 of the women had no signs of brain disorders when they were alive, the other 33 had Alzheimer's disease. The researchers found women with Alzheimer's were less likely to have male DNA in their brains than women without such a diagnosis.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The most important implication of our findings is the potential for both positive and negative consequences of microchimerism in the brain for a number of different diseases that affect the brain, including degenerative diseases and cancer," researcher William Chan, an immunologistat the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, told LiveScience.

Previous work on microchimerism suggested fetal cells might protect against breast cancer and aid tissue repair in the mothers, but also could boost the risk of colon cancer and help incite autoimmune diseases, in which a person's body is mistakenly attacked by its own immune system.

Future research may want to examine whether fetal cells in the brain play a role in Alzheimer's disease. Past research suggested Alzheimer's is more common in women who had a high number of pregnancies than in childless women.

"At present, it is unknown whether microchimerism in the brain is good or bad for health," Chan said. "We think it is likely that microchimerism imparts benefit in some, but in other situations may contribute to a disease process. Further studies are required."

One of the limitations of the new research is that the number of brains studied was relatively small.

In addition, "we were not able to obtain pregnancy history information for most of the women studied, so it is not currently possible to interpret our findings as positive or negative for Alzheimer's disease," Chan said. "The study also did not determine what types of cells the microchimeric cells are, a subject that we hope to address in future work."

The researchers also want to see what effects a mother's cells might have in her offspring's development and health, researcher Lee Nelson, a physician at the Hutchinson center, told LiveScience.

The scientists detailed their findings online Sept. 26 in the journal PLoS ONE.