Making Decisions at the Speed of Sight

Inside Science Minds presents an ongoing series of guest columnists and personal perspectives presented by scientists, engineers, mathematicians, and others in the science community showcasing some of the most interesting ideas in science today.

(ISM) -- How does the brain connect what we see in the world with how we behave?

This question launched my project to use the scientific understanding of human perception to better understand why the thumbnail images that preview online videos have so much influence over the number of clicks or views the video receives.

I am a cognitive neuroscientist, working with a small group of researchers at Carnegie Mellon University. Our goal is to understand how the brain’s visual system relates to people's slight positive or negative reactions to ordinary objects, which we call micro-valences.

It's not news to anyone that spotting a special memento can inspire feelings of nostalgia, or that seeing a blood-covered weapon can stoke a feeling of fear. But as scientists, the team I work with is more concerned with how the objects that we encounter every day, such as pens and coffee mugs, make people feel.

From the outset, our efforts aimed to uncover whether humans perceive the very subtle micro-valences in the objects and images encountered on a daily basis, such as coffee mugs and pens. This matters, because the majority of people spend far more time reacting to relatively neutral items than they do to items that inspire visceral reactions.

We borrow the term valence from chemistry. Instead of referring to an atom's positive or negative charge, we use it to describe the positive or negative perception associated with an image.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Valence is simpler than emotion, or preference, or value; it should be thought of as a very rough, very rapid and automatic snapshot of perception that the brain computes in order to estimate likability of an object. Instead of thinking about what constitutes valence, it is perhaps more helpful to think why we even see valence.

Imagine for a moment you are sitting in a coffee shop reading the newspaper, enjoying a beverage, when someone bursts in holding up a gun. You immediately sense danger and prepare to respond. How did your brain know that the gun was a dangerous object? In the lab, we have shown that most people detect a negative valence as early as 17 milliseconds after the participant sees the gun. This experiment introduces a critical question, namely -- how does the brain’s visual system know to evaluate the valence of the gun in that specific moment of danger? The answer is that the brain doesn't know in that specific moment; but rather it constantly assigns most incoming information some degree of positive or negative, in preparation for a moment such as that with the gun.

It follows that objects are rarely seen as neutral, and instead almost all objects generate the perception of valence, regardless of how subtle. My colleagues and I tested this hypothesis by having participants look at different images on the computer and respond in a way that indicates their unconscious perception of valence. We found that individuals from the same culture or background tend to share similar perceptions of valence.

Understanding valence is critical to understanding the aspects of our behavior associated with making choices. We demonstrated that objects perceived to be positive were more likely to be selected in a choice task. We found this to be true not just for whole objects, but even for scrambled objects and novel shapes, suggesting people see valence in all sorts of visual information.

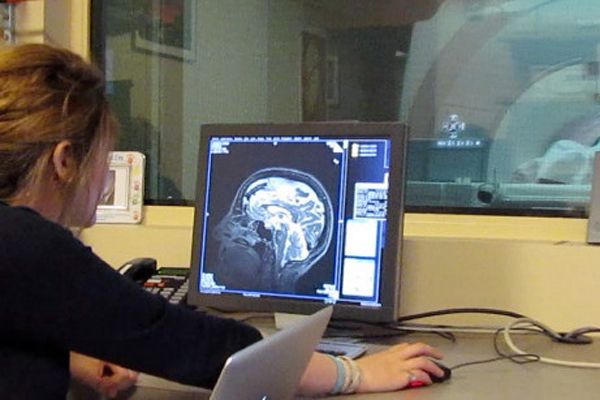

By using a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging, we were able to look into the human brain and see whether these choices were generated by a visual signal. The results were striking. Valence is represented in the brain along a continuum that ranges from strongly positive to strongly negative. This continuum is highly sensitive to miniscule differences in valence. Where an image falls on the continuum indicates how likely it is for that image is to be chosen. And as we initially predicted, valence is computed upon seeing the object, demonstrated by effects of valence in regions of the brain known to process exclusively visual information.

It's not a stretch of the imagination to see the commercial impact of valence. The ability to predict people's automatic and unconscious response to subtle differences in everyday visual information is highly valuable at a time when visual images dominate our experiences, both online and in stores. As those experiences become ever more digital, publishers are searching for strategies and turning to science to uncover ways of increasing online user engagement.

As we turn our effort to commercializing this basic science, we have learned that images on the Internet perceived to have a positive valence will generate higher clickthrough rates. The thumbnail pictures associated with online videos form the first touchpoint between the user and the publisher, which means the valence of the image is critical in determining the number of users that click to view the video. There is an intimate relationship between valence and click rates, and now the brain science of human perception help video publishers increase the number of views on their online videos.

In our laboratory, we say that what the brain sees is what the brain does. The way we see images and objects influences the choices that we make throughout life, from what car to buy, to what video to click on.

The other day as I was explaining valence, someone asked me if this meant that scientists have figured out aesthetics. I thought about it, and said no, but we have figured out a way to read people's aesthetic response in the brain.

Sophie Lebrecht is a cognitive neuroscientist at Carnegie Mellon University.

Inside Science Minds is supported by the American Institute of Physics.