NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has discovered what appears to be an ancient streambed, suggesting that water once flowed in large volumes — perhaps hip-deep in places — across the Martian surface.

Photos from the Curiosity rover have revealed several different rocky outcrops that contain stones cemented into a layer of conglomerate rock. Some of these stones are rounded and large, indicating that they were transported relatively long distances across the Red Planet surface by water.

This water flow was likely quite vigorous, perhaps akin to the flows produced by flash floods in desert areas here on Earth, researchers announced today (Sept. 27).

"From the size of gravels it carried, we can interpret the water was moving about 3 feet per second, with a depth somewhere between ankle and hip deep," Curiosity co-investigator William Dietrich, of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. [The Search for Water on Mars (Photos)]

"Plenty of papers have been written about channels on Mars with many different hypotheses about the flows in them," Dietrich added. "This is the first time we're actually seeing water-transported gravel on Mars. This is a transition from speculation about the size of streambed material to direct observation of it."

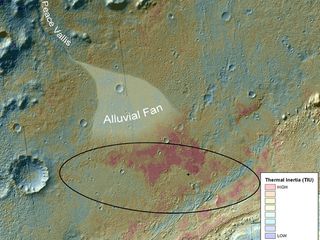

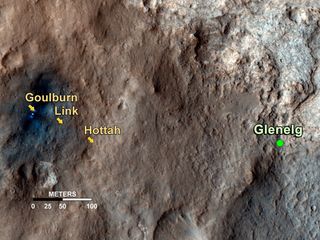

The findings came after researchers studied photographs of three different outcrops inside Gale Crater, where Curiosity touched down on Aug. 5.

The first outcrop, known as Goulburn, lies a few feet from the rover's landing site. Curiosity spotted the other two — called Link and Hottah — as it's been rambling toward an area called Glenelg, its first major science target.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Photos of Link really got the team thinking of long-ago stream flows, Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, of Caltech in Pasadena, told reporters today. And images of Hottah, which juts from the Red Planet surface at an odd angle, pretty much sealed the deal.

"Hottah looks like someone jack-hammered up a slab of city sidewalk, but it's really a tilted block of an ancient streambed," Grotzinger said in a statement.

On Earth, tilted outcrops are usually the result of tectonic activity. But Hottah could have been deformed by a nearby impact or other process, Grotzinger said.

The water on Mars likely flowed several billion years ago, researchers said, though an exact timeframe will be tough to determine. But the extent of the system that produced the outcrops — and the surrounding alluvial fan and channels — suggests that it wasn't produced in a single shot.

Rather, water was likely flowing over a relatively long chunk of time, scientists said.

"I'm comfortable to argue that it's certainly beyond the thousand-year timescale, but we're still gathering data to go further with that," Dietrich told reporters today.

The team has not yet analyzed Link or Hottah with Curiosity's 10 different science instruments; rather, the researchers' conclusions are based on images of Mars snapped by the rover's Mast Camera. But those pictures capture plenty of evidence, Grotzinger said.

"In some cases, when you do geology, a picture's worth a thousand words," he said.

The $2.5 billion Mars rover Curiosity is about 50 days into a roughly two-year mission to determine if the Gale Crater area has ever been capable of supporting microbial life.

Despite the outcrop discoveries, the six-wheeled robot's ultimate destination remains the base of Mount Sharp, a 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) mountain that rises from Gale's Center. The mysterious mountain's foothills show signs of long-ago exposure to liquid water.

"A long-flowing stream can be a habitable environment," Grotzinger said. "It is not our top choice as an environment for preservation of organics, though. We're still going to Mount Sharp, but this is insurance that we have already found our first potentially habitable environment."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.