Sea Creature Fossils Reveal Prehistoric Division of Labor

Ancient colonies of plankton were surprisingly good at cooperation, according to a new look at a very old fossil.

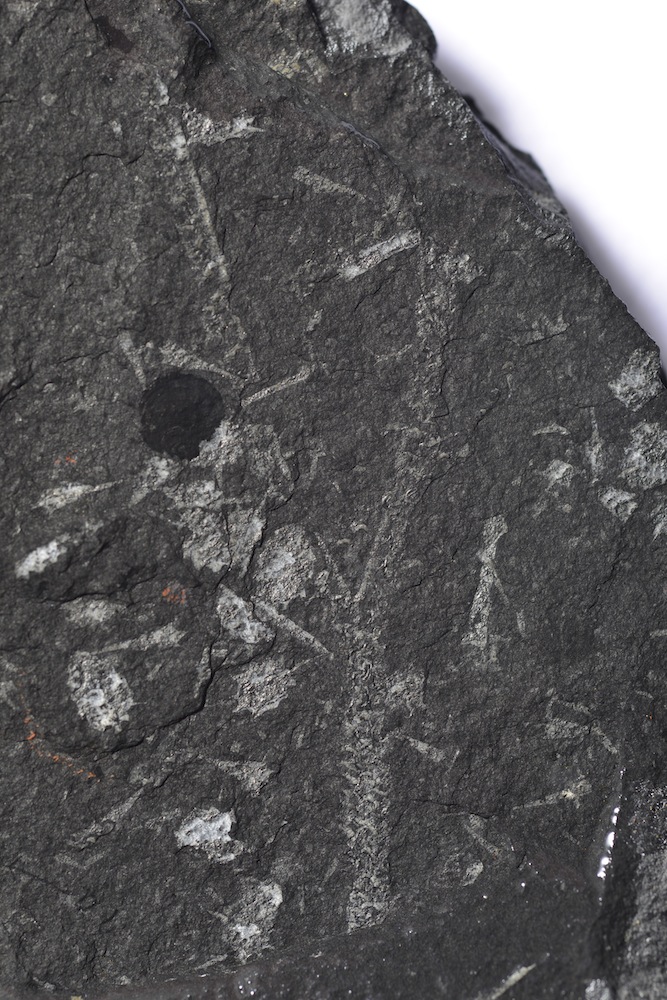

The slab of rock preserves the remains of a graptolite colony, which leaves fossils that look almost like hieroglyphics etched in stone. Graptolites were early animals that first arose nearly half a billion years ago. They almost entirely died out at the end of the Ordovician period about 443 million years ago. While no graptolites survive today, scientists believe they are most closely related to an unusual group of worm-like animals called pterobranches, which build and live in tubes on the ocean floor — though graptolites were more skilled builders, said study researcher Jan Zalasiewicz, a University of Leicester geologist.

"They are also animal architects (they build their own living tubes) but these are rather untidy, simple structures in comparison to the finely engineered, tightly organized living quarters of the graptolites," Zalasiewicz wrote in an email to LiveScience.

Just as modern coral leave behind amazing structures when they die, graptolites left behind the skeletons of their homes when they went extinct. These fossils are common, but it wasn't until Zalasiewicz was examining a museum specimen that he noticed something strange: The connections between different parts of the colony were not identical.

"The light caught one of the fossils in just the right way, and it showed complex structures I had never seen in a graptolite before," Zalasiewicz said in a statement. "It was a sheer stroke of luck … one of those eureka moments."

In some parts of the colony, Zalasiewicz said, the connections between individual animals looked like "slender criss-crossing branches." Others had odd hourglass shapes. Zalasiewicz and his colleagues reported the discovery online Aug. 9 in the journal Geological Magazine.

These fossil remnants suggest that graptolite colonies featured a division of labor, Zalasiewicz said, with some individual animals responsible for feeding and others for building. (Graptolites sported long, tentacled arms for feeding.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There is clear evidence here of polymorphism — that is, of substantially different physical patterns of connection along the colony," Zalasiewicz said. "This suggests division of function within the colony also, which might help explain the extraordinary sophisticated 'building' abilities that these animals possessed."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.