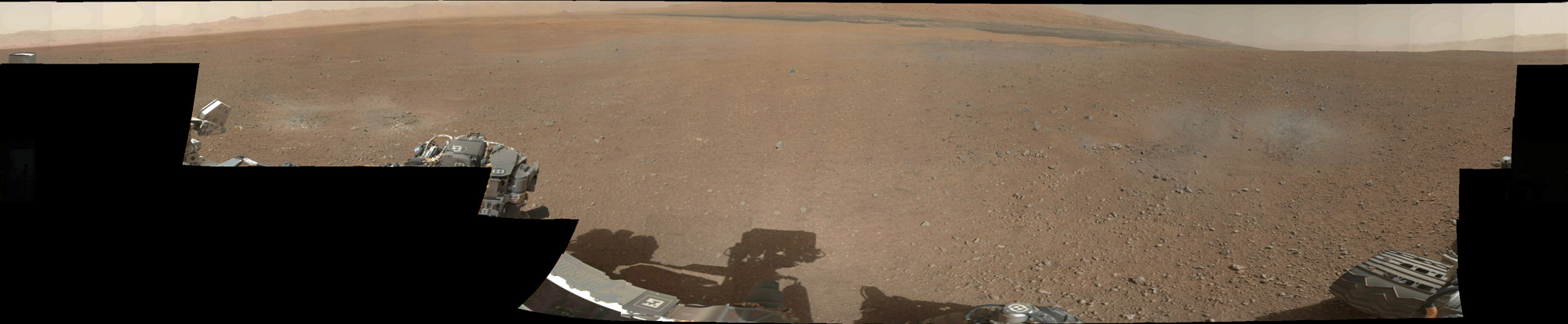

Weather On Mars Surprisingly Warm, Curiosity Rover Finds

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity is enjoying some nice, warm weather on the Red Planet — and spring hasn't even come to its landing site yet.

Curiosity's onboard weather station, which is called the Remote Environment Monitoring Station (REMS), has measured air temperatures as high as 43 degrees Fahrenheit (6 degrees Celsius) in the afternoon. And temperatures have climbed above freezing during more than half of the Martian days, or sols, since REMS was turned on, scientists said.

These measurements are a bit unexpected, since it's still late winter at Gale Crater, the spot 4.5 degrees south of the Martian equator where Curiosity touched down on Aug. 5.

"That we are seeing temperatures this warm already during the day is a surprise and very interesting," Felipe Gómez, of the Centro de Astrobiología in Madrid, said in a statement. [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

Curiosity's main goal is to determine if the Gale area is, or ever was, capable of supporting microbial life. Most researchers think present-day Mars is too dry and cold to host life as we know it, but they may have to rethink some of their assumptions if temperatures climb considerably through the spring and summer.

"If this warm trend carries on into summer, we might even be able to foresee temperatures in the 20s [Celsius], and that would be really exciting from a habitability point of view," Gómez said. "In the daytimes, we could see temperatures high enough for liquid water on a regular basis. But it’s too soon to tell whether that will happen or whether these warm temperatures are just a blip.”

While Curiosity's days are relatively pleasant weather-wise, the same can't be said for the rover's nights. Air temperatures drop dramatically after the sun goes down, plunging as low as minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 70 Celsius) just before dawn, scientists said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such big swings occur because the effects of solar heating are much more pronounced on Mars than they are on Earth. The Red Planet's surface is much drier, and its atmosphere is just 1 percent as thick as Earth's.

REMS measurements also suggest that atmospheric pressure is on the rise at Gale Crater, researchers said. This information is in line with mission scientists' expectations.

In winter, Mars gets cold enough for carbon dioxide at the poles to freeze, forming seasonal "dry ice" caps. Since carbon dioxide dominates the Red Planet's thin atmosphere, this freeze-out process causes pressures to vary from season to season.

Models and data from previous missions had predicted that Curiosity would land when pressures were around their lowest. The rover's measurements have borne this out, rising from a daily average of around 730 pascals during Curiosity's first three weeks on Mars to about 750 pascals more recently, researchers said.

“The pressure data show a very significant daily variation of pressure, following a fairly consistent cycle from sol-to-sol," said REMS principal investigator Javier Gómez-Elvira. "The minimum is near 685 pascals and the maximum near 780 pascals."

Even that maximum value is nowhere near what we're used to here on Earth. Average atmospheric pressure at sea level on our planet is 101,325 pascals — about 140 times what Curiosity is experiencing inside Gale Crater.

REMS sustained some minor damage during landing, when rocks kicked up by the engines on Curiosity's sky crane descent stage apparently knocked out wind sensors on one of the instrument's two booms.

But wind sensors on the other boom are working fine, so mission scientists don't anticipate too much of an impact.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.