The first televised debate tonight (Oct. 3) in Denver between President Barack Obama and Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney will cover domestic policy — including, perhaps, the two men's visions for America's space program.

The differences between Obama and Romney are relatively clear in some arenas, such as tax policy and the role and size of government. But it's tougher to assess how their space plans stack up, in large part because Romney has offered few details at this stage.

Indeed, Romney says those details will be worked out later, after consultation with a broad range of experts in the space community.

"He will bring together all the stakeholders — from NASA, from the Air Force, from our leading universities, and from commercial enterprises — to set goals, identify missions, and define a pathway forward that is guided, coherent, and worthy of our great nation," the Romney campaign wrote in a space policy paper issued late last month.

With that important caveat noted, here's a brief look at the stated space priorities of Obama and Romney, and where each may take the nation's space program over the next four years. [Gallery: President Obama and NASA]

President Obama: Manned trips to an asteroid and Mars

In 2010, President Obama axed NASA's Bush-era Constellation program, which aimed to return humans to the moon by 2020. The decision followed on the heels of the Augustine Commission's report, which found Constellation to be significantly overbudget, underfunded and behind schedule.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Obama instead directed NASA to work toward getting astronauts to a near-Earth asteroid by 2025, then on to the vicinity of Mars by the mid-2030s. To make this happen, the agency is developing a huge rocket called the Space Launch System (SLS) and a crew capsule called Orion, which NASA hopes will begin carrying astronauts by 2021.

Despite the cancellation of Constellation, the SLS and Orion may still be used to help humans explore the moon in a decade or so. In fact, NASA deputy chief Lori Garver said last month that a manned lunar trip remains on the agency's agenda.

"We just recently delivered a comprehensive report to Congress outlining our destinations which makes clear that SLS will go way beyond low-Earth orbit to explore the expansive space around the Earth-moon system, near-Earth asteroids, the moon, and ultimately, Mars," Garver said during a speech at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics' Space 2012 conference in Pasadena, Calif.

"Let me say that again: We're going back to the moon, attempting a first-ever mission to send humans to an asteroid and actively developing a plan to take Americans to Mars," Garver added.

The Obama Administration has also encouraged NASA to hand over crew and cargo activities in low-Earth orbit to private American spaceflight firms. The goal is to have commercial spaceships fill the shoes of the space shuttle, whose July 2011 retirement was set in motion by the Bush Administration back in 2004.

That transformation has been proceeding, with NASA doling out a total of $1.4 billion over the last two years to companies developing crewed vehicles. The agency hopes at least two different private spaceships will be ferrying astronauts to and from the International Space Station by 2017. (Until that happens, the nation's station-bound astronauts will continue to fly aboard Russian Soyuz spacecraft.) [Special Report: The Private Space Taxi Race]

Things are happening more quickly on the cargo front. California-based SpaceX is slated to launch its first unmanned supply run to the space station this Sunday (Oct. 7), after its Dragon capsule aced a demonstration mission to the orbiting lab in May.

SpaceX holds a $1.6 billion NASA contract to make 12 such cargo flights. NASA also signed a $1.9 billion deal with Virginia firm Orbital Sciences Corp. for eight unmanned supply missions to the space station. Orbital plans to launch a demonstration flight to the station in the coming months.

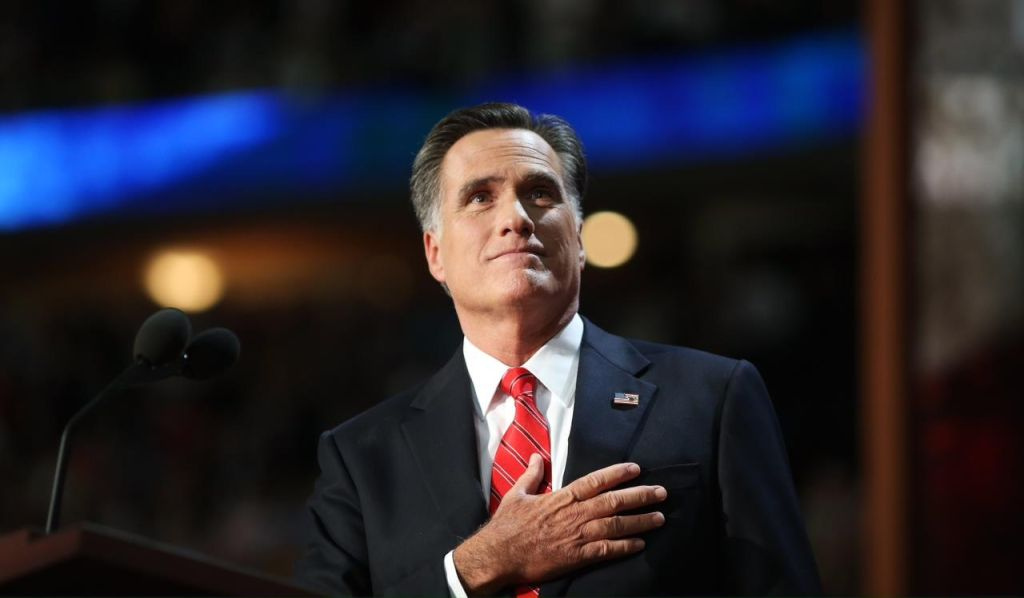

Mitt Romney: Keeping the U.S. on top

Romney and running mate Paul Ryan, a Republican congressman from Wisconsin, pledge to ensure that the United States remains the world leader in space exploration and space capabilities. The title of the campaign's space policy paper, after all, is "Securing U.S. Leadership in Space."

Much of the eight-page document is a critique of the Obama Administration, which the Romney campaign says has severely diminished the nation's proud space program.

"Over the past four years, the Obama Administration, through poor policy and outright negligence, has badly weakened one of the hallmarks of American leadership and ingenuity — our nation’s space program," the white paper reads.

Romney does not lay out a step-by-step fix for this alleged problem, instead promising broad commitments to work with international partners, strengthen America's national security space programs and revitalize the country's aerospace industry. The details will come later, Romney says, after conversations with many stakeholders in the space community.

The Republican nominee also says he'll continue to support the handover of spaceflight activities in low-Earth orbit to private American firms.

The campaign's policy statement gives no reason to suspect that a Romney presidency would set the country's space program on a dramatically different course than the one it's currently embarked upon, said space policy expert John Logsdon, a professor emeritus at George Washington University.

"It's not clear to me that there would be any fundamental differences," Logsdon told SPACE.com.

It's also probably safe to assume that a Romney-Ryan White House would not increase NASA's funding, which has ranged from $18.7 billion to $17.7 billion during Obama's presidency and stands at $17.7 billion in the proposed 2013 federal budget.

"A strong and successful NASA does not require more funding, it needs clearer priorities," the Romney policy paper reads.

Indeed, Romney has in the past expressed a lack of enthusiasm for big, expensive space exploration projects. In a Republican primary debate last January, for example, he said fellow candidate Newt Gingrich's plan to establish a manned moon base by 2020 was a bad idea.

"I'm not looking for a colony on the moon," Romney said during the debate. "I think the cost of that would be in the hundreds of billions, if not trillions. I'd rather be rebuilding housing here in the U.S."

"I spent 25 years in business," he added later in the debate. "If I had a business executive come to me and say they wanted to spend a few hundred billion dollars to put a colony on the moon, I'd say, 'You're fired.'"

While many people at NASA and across the space community will likely be watching tonight's debate intently, they shouldn't hold their breath waiting for moderator Jim Lehrer to ask a space question, Logsdon said.

"If it were in Florida, space may have become an issue," Logsdon said. "I don't think it's going to come up in Denver. I think it's a second- or third-order issue."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.