Vegetarian Dinosaurs Were Champion Chompers

Giant plant-eating dinosaurs may have been champion chewers up there with the likes of mammals such as horses, bison or elephants, researchers say.

The finding could help explain why these behemoths dominated the plains of Europe, Asia and North America during the last part of the age of dinosaurs, scientists added.

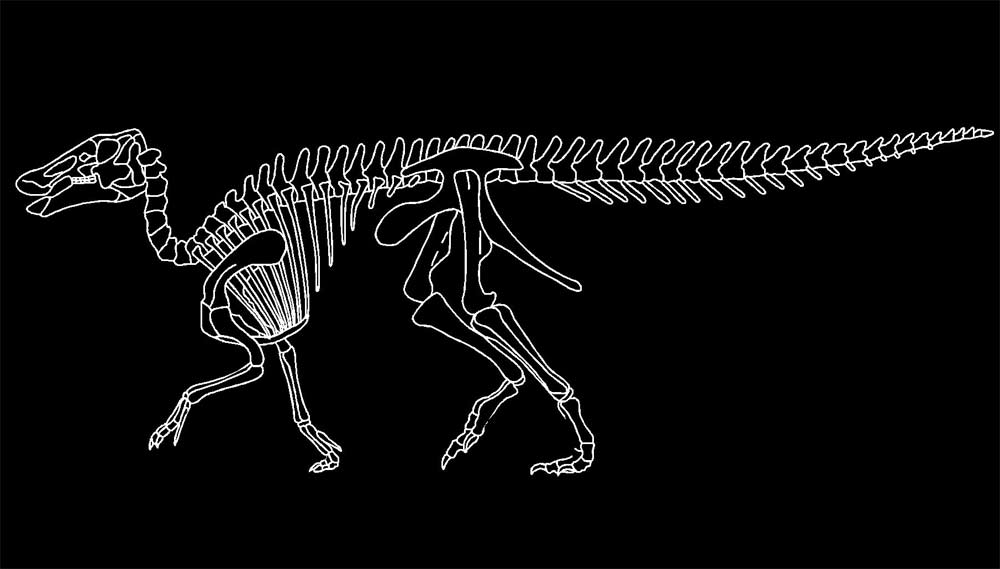

Duck-billed herbivores called hadrosaurids thundered across the world during the Late Cretaceous period, dating about 65 million to 100 million years ago. They grazed on horsetails, ferns and primitive flowering plantson the ground, and browsed on Earth's conifers.

The plants these dinosaurs fed on were tough and covered with hard, tooth-gouging particles. Hadrosaurids chewed their meals with teeth that possessed flattened grinding surfaces much like those of horses and bison. Some hadrosaurids sported up to 1,400 of these teeth, and were continually replacing them.

"They were like walking pulp mills — I suspect they could eat any kind of plant they ran into," said researcher Gregory Erickson, a paleobiologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee.

The chewing teeth of mammals can be relatively complex, possessing four major types of tissue of varying hardness. These combinations help keep the grinding ridges and valleys on a tooth's surface from wearing and breaking down. In contrast, most reptile teeth are comparably simple, with only two kinds of tissue — hard enamel and a softer bone-like material. [Paleo-Art: Stunning Dinosaur Illustrations]

"It didn't make sense to me that the complex surfaces we see in hadrosaur teeth could be done with the simple tooth tissues reptiles are supposed to have," Erickson said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

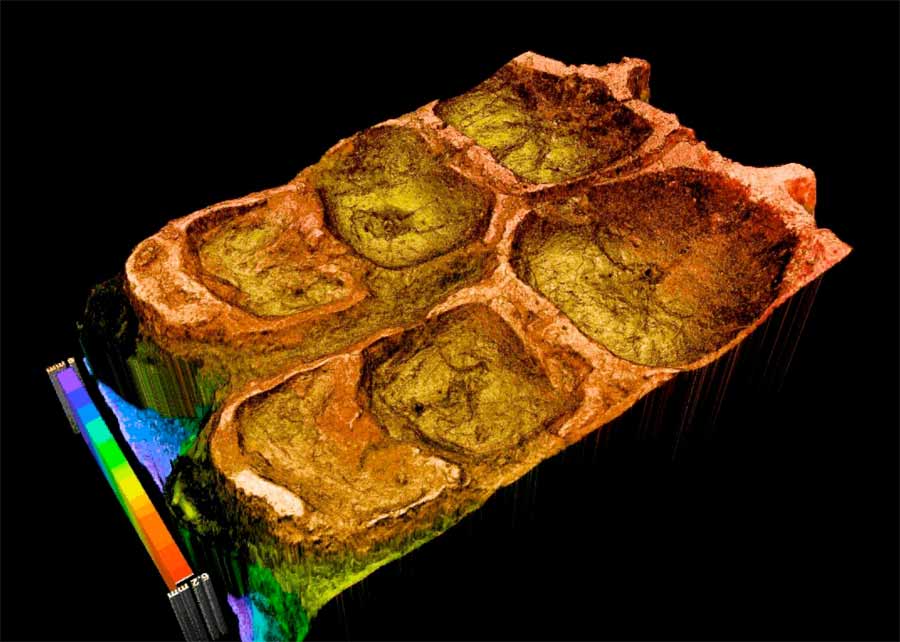

Now researchers find hadrosaurid teeth were far more complex than those of known reptiles — they were composed of six different types of tissue.

"They were as sophisticated, if not more sophisticated, than any known mammal," Erickson told LiveScience.

After analyzing fossil hadrosaurid teeth with microscopy and X-rays and by testing them with diamond-tipped probes, the researchers found the way tissues were distributed varied substantially within each tooth. This would allow a single tooth to assume different forms and functions as the tooth changed over time, exposing different surfaces as the teeth migrated across the chewing surfaces in the mouths of the dinosaurs over time.

The complexity of hadrosaurid teeth would have proved excellent tools for handling tough, gritty plants. This could explain why this group of dinosaurs was so common.

Now Erickson and his colleagues plan to use these methods to investigate teeth from both extinct and living reptile and mammal species to see how these groups diversified in response to their diet.

"We still don't have a good understanding even of how horse teeth work," Erickson said.

The scientists detail their findings in tomorrow's (Oct. 5) issue of the journal Science.