Did NASA's Voyager 1 Spacecraft Just Exit the Solar System?

It will be another giant leap for mankind when NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft becomes the first manmade object to venture past the solar system's edge and into the uncharted territory of interstellar space. But did this giant leap already occur?

New data from the spacecraft indicate that the historic moment of its exit from the solar system might have come and gone two months ago. Scientists are crunching one more set of numbers to find out for sure.

Voyager 1, which left Earth on Sept. 5, 1977, has since sped to a distance of 11.3 billion miles (18.2 billion kilometers) from the sun, making it the farthest afield of any manmade object. (It has 2 billion miles on its twin, Voyager 2, which took a longer route through the solar system.) Still phoning home (via radio transmissions) after 35 years, the Voyagers are the longest operating spacecraft in history.

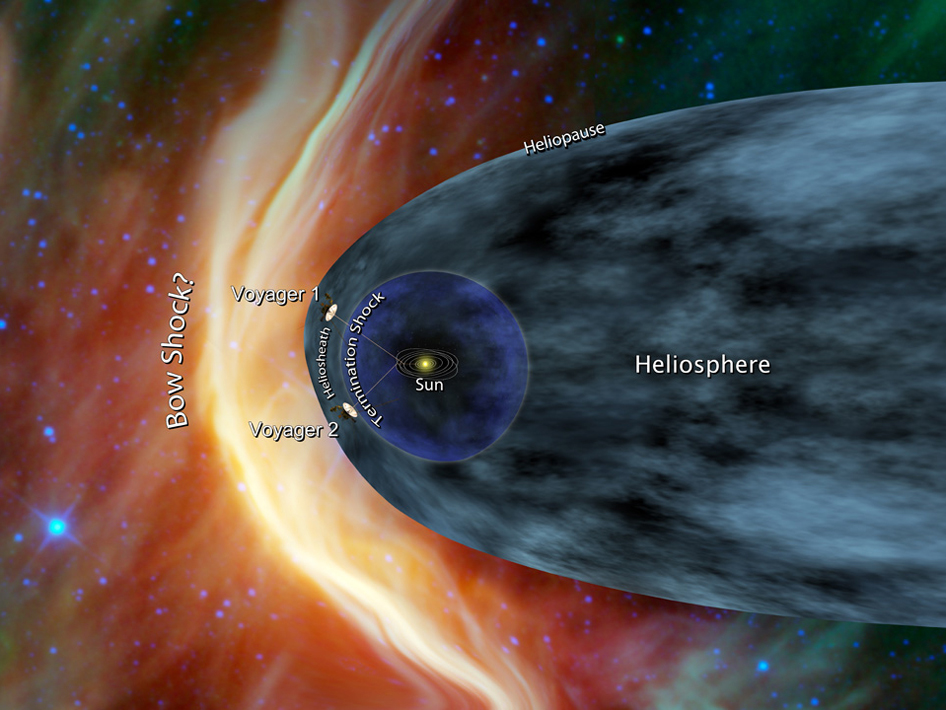

For two years now, data beamed back to Earth by Voyager 1 has hinted at its close approach to the edge of the solar system, a pressure boundary called the heliopause. At this boundary, the bubble of electrically charged particles blowing outward from the sun (called the heliosphere) exactly counterbalances the inward pressure of the gas and dust from interstellar space, causing equilibrium between the two. But scientists have had trouble figuring out what, exactly, happens at or near this boundary — making it hard to tell whether Voyager has crossed it.

In 2010, Voyager passed the point where the solar wind, a stream of charged particles flowing outward from the sun, seemed to reach the end of its leash. The probe's detectors indicated that the wind had suddenly died down, and all the surrounding solar particles were at a standstill.

This "stagnation region" came as a surprise. Scientists had expected to see the solar wind veer sideways when it met the heliopause, like water hitting a wall, rather than screech to a halt. As Voyager scientists explained in a paper published last month in Nature, the perplexing collapse of the solar wind at the edge of the heliosphere left them without a working model for the outer solar system.

"There is no well-established criteria of what constitutes exit from the heliosphere," Stamatios Krimigis, a space scientist at Johns Hopkins University and NASA principal investigator in charge of the Voyager spacecraft's Low-Energy Charged Particle instrument, told Life's Little Mysteries. "All theoretical models have been found wanting."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, Ed Roelof, also a space scientist at Johns Hopkins who works with Voyager 1 data, said that in any model of the heliopause, an object exiting through it should experience three changes: a sharp rise in the number of collisions with cosmic rays (high-energy particles from space), a dramatic drop in the number of collisions with charged particles from the sun, and a change in the direction of the surrounding magnetic field.

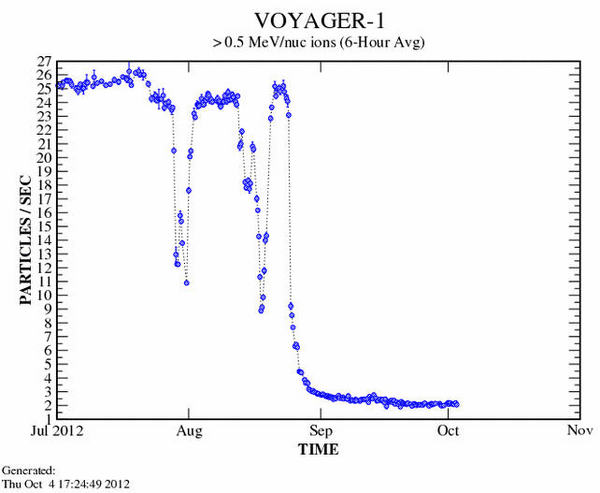

Based on two of those criteria, Voyager 1 looks as if it passed through the heliopause at the end of the summer. Since May, the spacecraft has experienced a steady rise in the number of collisions with particles whose energies are greater than 70 Mega-electron-volts, indicating they are probably cosmic rays emanating from supernova explosions far beyond the solar system. The level of these cosmic ray collisions jumped significantly in late August.

As first reported by Houston Chronicle science blogger Eric Berger, that jump coincided with another change in late August: The spacecraft also experienced a dramatic drop in the number of collisions with low-energy particles, which probably originated from the sun. [See graph]

In short, in late August, cosmic ray collisions sharply rose, and solar particle collisions sharply fell: two indicators of a transition through the heliopause.

"Most scientists involved with Voyager 1 would agree that [these two criteria] have been sufficiently satisfied," said Ed Roelof, also a space scientist at Johns Hopkins who works with Voyager 1 data.

To officially declare Voyager's crossing, the scientists need to check if the third condition holds. "Point 3 (the change in magnetic field direction to that of the interstellar field beyond the influence of the sun) is critical because, even though there is debate among astrophysicists as to what direction the field will lie in, it seems unlikely that it is the direction that we have been seeing at Voyager 1 throughout the most recent years," Roelof wrote in an email.

"That is why we are all awaiting the analysis of the most recent magnetic field measurements from Voyager 1. We will be looking for the expected change to a new and steady direction. That would drop the third independent piece of evidence into place — if indeed that's what will be seen," he said.

The scientists could not say when the magnetic field analysis would be finished. But when it is — and if it also indicates that the field's direction recently underwent a change — the world will know. "Once we have a consensus within the team we will inform NASA for a proper announcement," Krimigis said.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover or Life's Little Mysteries @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.