Mummy with Mouthful of Cavities Discovered

Around 2,100 years ago, at a time when Egypt was ruled by a dynasty of Greek kings, a young wealthy man from Thebes was nearing the end of his life.

Rather than age, he may have succumbed to a sinus infection caused by a mouthful of cavities and other tooth ailments, according to new research on the man's odd dental filling.

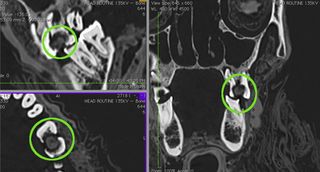

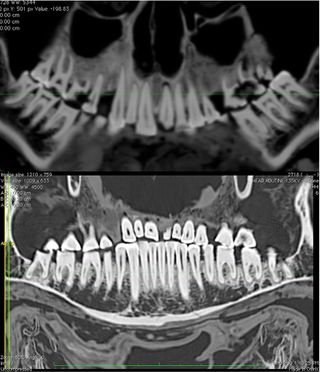

Recently published CT scans of his mummified body allowed researchers to reconstruct details of his final days.

The man, whose name is unknown, was in his 20s or early 30s, and his teeth were in horrible shape. He had "numerous" abscesses and cavities, conditions that appear to have resulted, at some point, in a sinus infection, something potentially deadly, the study researchers said.

The pain the young man suffered would have been beyond words and drove him to see a dental specialist. Dentistry was nothing new in Egypt, ancient records indicate that it was being practiced at least as far back as when the Great Pyramids were built. Dental problems were also not unusual, the coarsely ground grain ancient Egyptians consumed was not good for the teeth. [Gallery: Scanning Mummies for Heart Disease]

A modern-day dentist would have a hard time dealing with the young man's severe condition and one can imagine that the ancient dentist must have felt overwhelmed. The researchers noted that even today infections associated with the teeth pose a "serious health risk."

Nevertheless the ancient specialist tried something to relieve his suffering. Using a piece of linen, perhaps dipped in a medicine such as fig juice or cedar oil, the expert created a form of "packing" in the young man's biggest and perhaps most painful cavity, located on the left side of his jaw between the first and second molars.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The packing acted as a barrier to prevent food particles from getting into the cavity, with any medicine on the linen helping to ease the pain, the study researchers said. Sadly, while this likely helped the young man out, he would succumb shortly after, perhaps in just a matter of weeks. Researchers can't say for sure the cause of death, but the sinus infection is a good possibility.

When he died he was mummified, his brain and many of his organs taken out, resin put in and his body wrapped. Curiously, embalmers left his heart inside the body, a sign perhaps of his elite status, researchers say.

After being mummified he was likely put in a coffin and given funerary rites befitting someone of his wealth and stature. Where he was laid to rest in Thebes isn't known, as his story picks up again in 1859 when James Ferrier, a businessman and politician, brought the mummified body (the whereabouts of the coffin is unknown) to Montreal, where today it lies in the Redpath Museum at McGill University.

Reconstructing his story

To figure out the mummy's story, researchers led by Andrew Wade, then at the University of Western Ontario, used new high-resolution CT scans of his teeth and body, reporting their dental-packing discovery recently in the International Journal of Paleopathology. Researchers said this is the first known case of such packing treatment done on an ancient Egyptian. Unlike a modern-day dental filling, this one didn't aim to stabilize the tooth.

"The dental treatment, filling a large inter-proximal cavity [a cavity between two teeth] with a protective, likely medicine-laden, barrier is a unique example of dental intervention in ancient Egypt," the team writes in their journal article.

Wade, who completed the study while working on his doctorate, pointed out in an interview with LiveScience that advances in CT technology made this discovery possible. The small linen mass was initially found during a scan in the mid-1990s, but the scanning resolution of the time was too low to allow a full analysis. The high-resolution scanner his team used was six times as powerful.

"The technology's come a long way in the last 20 years," he said.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.