Singing Mice Can Change Their Tune

The newest singing sensation in the animal kingdom? Mice.

The creatures not only sing ultrasonic melodies high above sopranos, distinct from their regular squeaks, but they also learn new tunes from each other, researchers report today (Oct. 10).

Song learning is known to exist in humans, dolphins, songbirds and parrots, but the new research overthrows a 50-year assumption that mouse vocalizing is inborn and instead shows that mice have a rudimentary vocal system to control their vocal cords and learn new tunes.

"The mouse brain and behavior for vocal communication is not as primitive and as innate as myself and many other scientists have considered it to be," senior author Erich Jarvis, a neurobiologist at Duke University, told LiveScience. "Mice have more similarities in their vocal communication with humans than other species like our closest relatives," Jarvis added, referring to chimpanzees.

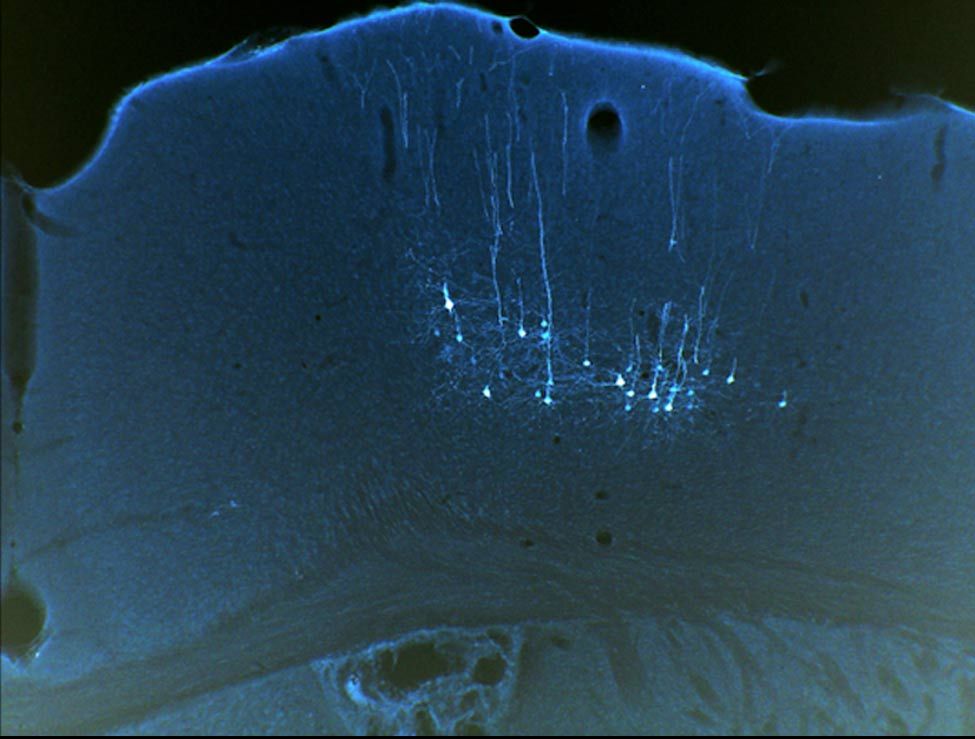

Generally, vocalizing comes from a coordinated effort between the brain's motor cortex, which controls voluntary muscles, and the vocal cords in the larynx. Jarvis and colleagues found a rudimentary indirect connection in mice between the two, absent in chimpanzees and monkeys.

The findings may also impact human speech disorders such as those found in autism, commonly studied in mice genetically engineered to mimic the disorders.

Singing new songs

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jarvis, who studies how language works and evolves, set out to demonstrate and verify that mice didn't have brain connections to learn singing behavior.

In their study, the researchers destroyed the motor control region in mice and then tested their singing abilities. The altered mice could still sing, "but they weren't able to modulate or stay on pitch on their songs as they were before," Jarvis said. [10 Cool Facts About the Brain]

The inborn ability to vocalize is built into the brain stem of mice, whereas pitch modulation and melody comes from the rudimentary motor control center, Jarvis hypothesized.

Next, the researchers wanted to determine just how modifiable these songs were. Previous research had shown male mice become mini-Pavarottis when sexually excited by the female scent. But the new research suggests mice are able to mimic new songs.

These results came to light after placing two mice strains with different vocal ranges, like tenors and basses, in the same cage with females. After eight weeks, the tenors sang in the lower bass range. Some basses sang higher, but most continued to sing in the same register.

In other words, the mice changed their tune in front of the ladies so they all sounded pretty much the same, Jarvis said.

What's next

However, other researchers disagreed that the tenors were actually learning a new pitch by converging with the bass pitch.

"Pitch convergences are also known from non-vocal learners and the number of tested animals is very low to see whether the discovered effect is reliable," Kurt Hammerschmidt, senior scientist at the German Primate Center in Goettingen, Germany, wrote in an email. Hammerschmidt was not involved in the study and wrote that the convergence could be a side effect of the low number of mice tested.

In future research, Jarvis plans to examine the role genes play in the process of mouse vocalizing, dig into the details of the rudimentary brain connections to determine how similar they are to humans and songbirds and lastly, to try to create mice with enhanced circuitry to more resemble that of humans or songbirds.

"What if we can enhance that [mouse brain] connection to be more songbird like? Would we get mice to be better imitators?" Jarvis said.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.