Explosive Volcanic Eruptions Caused By Mixing Magmas

Meteorologists know mixing cold air and warm air triggers powerful thunderstorms. Now, geologists have discovered a similar phenomenon at work beneath one of Europe's most hazardous volcanoes.

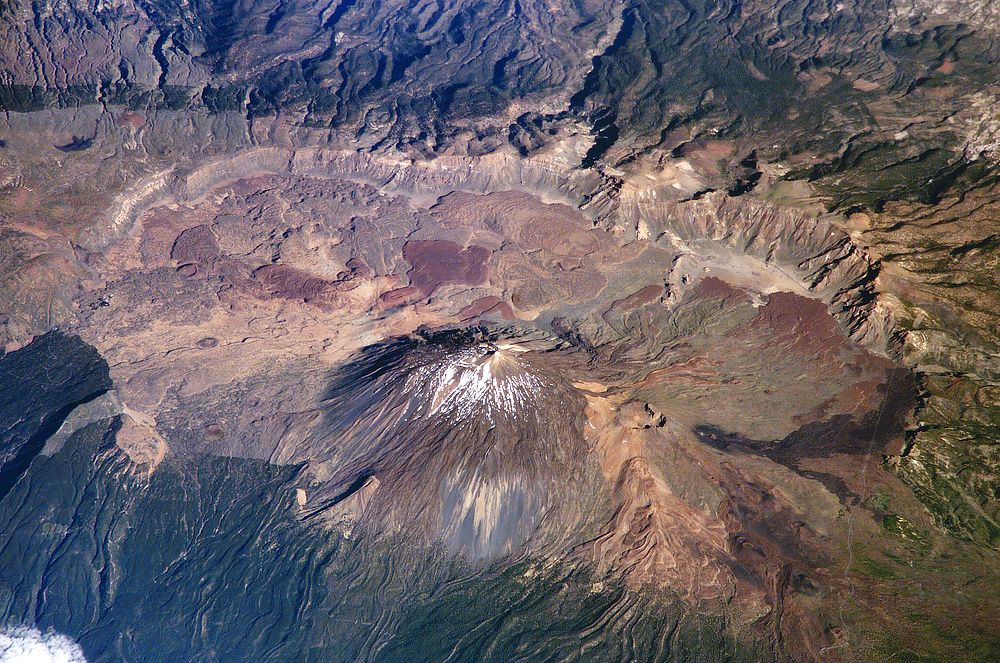

The Las Cañadas volcano, on the island of Tenerife near Spain, last exploded approximately 170,000 years ago, and is due for another eruption. Researchers believe they have identified what happens in the volcano's magma chamber just prior to such massive eruptions, which could help scientists predict the next blast before it happens.

A new study into the volcano reveals that pre-eruption mixing within the magma chamber — where older, cooler magma mixed with younger, hotter magma — triggered three previous large-scale eruptions. The mixing is like "putting a red-hot rock into a cup of ice," said study author Rex Taylor, of the University of Southampton in Britain.

The researchers made their find by analyzing crystal cumulate nodules (igneous rocks formed by the accumulation of crystals in magma) in deposits from prior eruptions. The nodules provide a record of the changes in the magma chamber until the moment the volcano erupted."Rims of crystals in the nodules grew from a very different magma, indicating a major mixing event occurred immediately before eruption," Taylor said in a statement.

Now that the volcano's trigger is known, monitoring changes in the magma chamber could help volcanologists predict a coming eruption. Las Cañadas, also called Mount Teide, is one of 16 Decade Volcanoes identified for study by the United Nations because of the volcano's history of destructive eruptions and its proximity to populated areas.

The volcano has frequent small lava flows every 100 years or so. Large explosions happen about every 100,000 years. These eruptions spew ash 15 miles (25 kilometers) into the air and collapse the volcanointo a caldera, sending pyroclastic flows (clouds of flowing hot gas and debris) across the island, which has more 200,000 inhabitants.

The big blasts expel more than 25 times more material than the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland. Prevailing winds would normally take the ash out over the Atlantic, Taylor told OurAmazingPlanet in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings are detailed in the Oct. 12 issue of the journal Scientific Reports.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.