Saturn's Moon Titan Has Soft and Crusty Surface, Probe Landing Reveals

The surface of Saturn's huge moon Titan has the consistency of soft, wet sand with a fragile crust on top, a new analysis of a nearly eight-year-old space probe landing suggests.

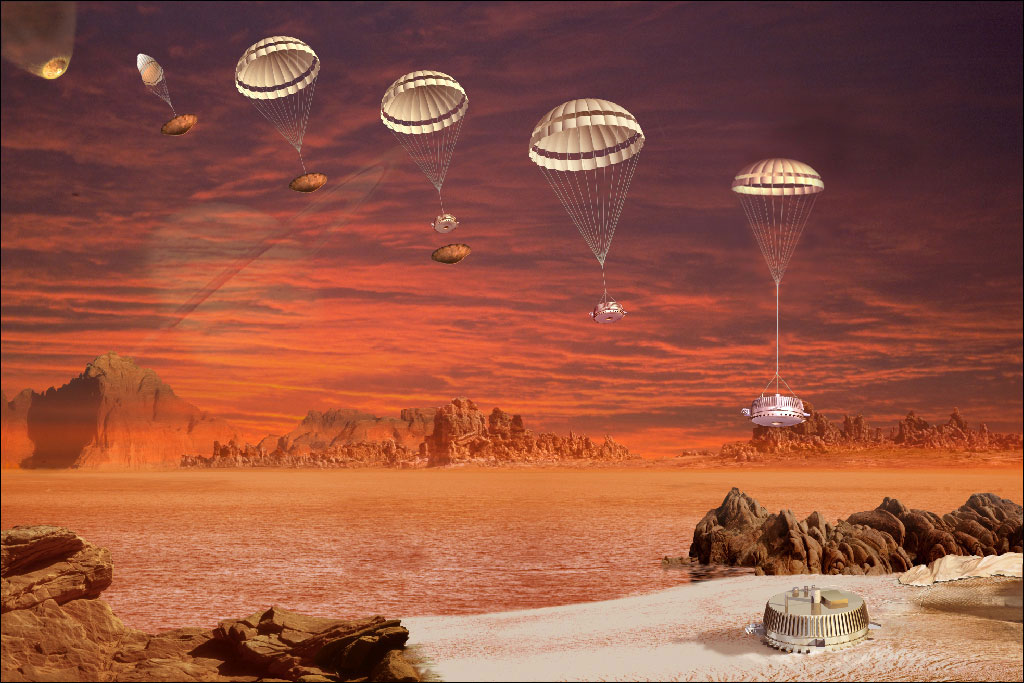

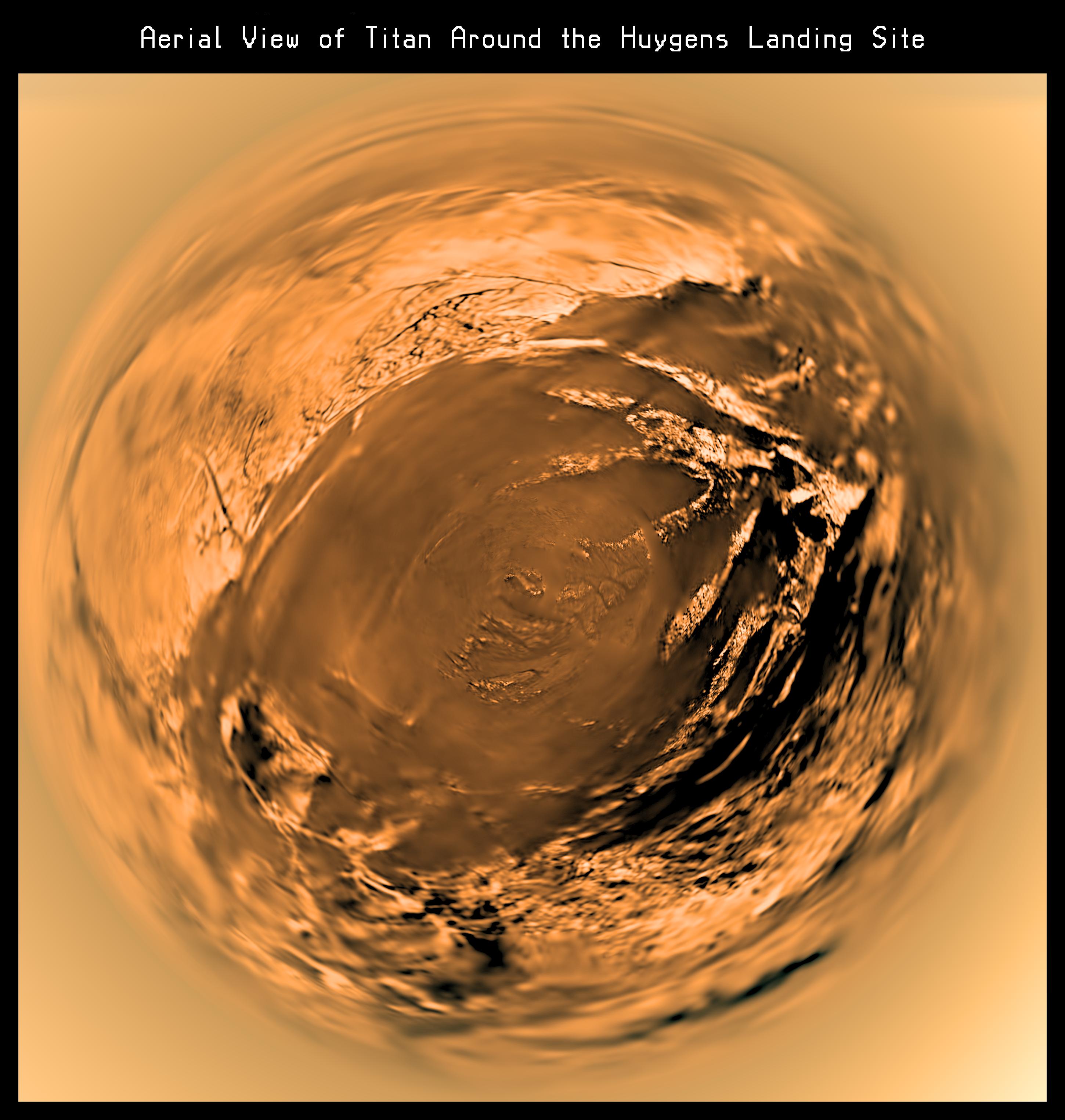

Researchers reconstructed the European Space Agency's Huygens probe landing on Titan, which occurred in January 2005. They determined that Huygens bounced, slid and wobbled to a stop 10 seconds after first making contact with the moon.

The study — which incorporated data from Huygens' instruments and results from computer simulations and a drop test with a model — found that the 400-pound (181-kilogram) probe made a dent 4.7 inches deep (12 centimeters) upon touching down.

Huygens then slid 12 to 16 inches (30 to 40 cm) and wobbled back and forth five times before finally coming to a rest, researchers said. [Huygens Probe's Landing Reconstructed (Video)]

"A spike in the acceleration data suggests that during the first wobble, the probe likely encountered a pebble protruding by around an inch from the surface of Titan, and may have even pushed it into the ground, suggesting that the surface had a consistency of soft, damp sand," study lead author Stefan Schröder, of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, said in a statement.

This conclusion is broadly consistent with previous studies of the landing, which determined that Titan's surface is likely quite soft. But the new analysis suggests that a sort of crust lies on top of the soft stuff.

"It is like snow that has been frozen on top," said co-author Erich Karkoschka of the University of Arizona. "If you walk carefully, you can walk as on a solid surface, but if you step on the snow a little too hard, you break in very deeply."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fact that Huygens bounced and wobbled rather than simply "splatted" suggests that the moon's surface was dry when it touched down, researchers said. This interpretation is bolstered by the dusty cloud the probe seems to have kicked up.

"We also see in the Huygens landing data evidence of a fluffy dust-like material — most likely organic aerosols that are known to drizzle out of the Titan atmosphere — being thrown up into the atmosphere and suspended there for around four seconds after the impact," Schröder said.

So methane or ethane rain, which pools into huge lakes on Titan's surface, likely hadn't fallen immediately before Huygens — which was ferried to Titan by NASA's Cassini spacecraft — touched down.

"This study takes us back to the historical moment of Huygens touching down on the most remote alien world ever visited by a landing probe," said Nicolas Altobelli, the European Space Agency's Cassini-Huygens project scientist. "Huygens data, even years after mission completion, are providing us with a new dynamical 'feeling' for these crucial first seconds of landing."

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission is a collaboration involving NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. It launched in 1997 and arrived at the Saturn system in 2004. While Huygens ceased sending data home about 90 minutes after landing on Titan, Cassini is still going strong, and its mission to study Saturn and its moons has been extended through at least 2017.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.