Rotten Eggs: Secret Ingredient for Suspended Animation?

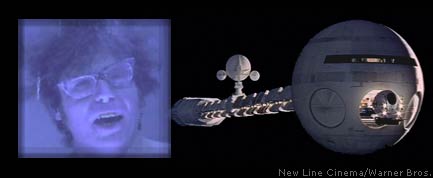

Science fiction usually sticks hibernating spaceflyers in glowing capsules of goo, but a real-life ingredient for suspended animation may not be too far off, scientists say.

Hydrogen sulfide is the key stinky compound in rotting eggs and swamp gas. New research shows it can slow down a mouse's metabolism, or the consumption of oxygen, without dampening the flow of blood.

"A little hydrogen sulfide gas is a way to reversibly and, apparently, safely cut metabolism in mice," Dr. Warren Zapol, a medical researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, told LiveScience. "There seemed to be no side harmful effects to the mice after hours of breathing it in. They got sluggish, but still responded to a pinch on the tail."

Zapol, also chief of anesthesia and critical care at the hospital, and his colleagues will detail their findings in the April issue of the journal Anesthesiology.

Heart of the problem

Previous studies showed hydrogen sulfide gas could slow down metabolism but never examined what happens to the circulatory system, the network of blood distribution commanded by the heart.

Zapol's team used ultrasound technology to view the hearts of mice as they inhaled hydrogen sulfide. After six hours, the heart rate of the mice halved, but their blood pressure remained normal, crucial to keeping blood adequately flowing through the body.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When you make everything sluggish, you'd think the heart would become sluggish, but it didn't," Zapol said.

He said that respiratory failure and other problems he expected to see weren't observed.

"I was surprised how well it worked," Zapol said. "You'd think poisoning the metabolism would dangerously slow it down, but it didn't really seem to interfere."

Suspended animation?

Zapol expects that combining hydrogen sulfide inhalation with chilling the body, another method of slowing down the body's machinery, could cut metabolism by up to 90 percent.

"Nine months in a spaceship heading out to Mars takes a lot of oxygen to burn, food and water to consume, and produces a lot of waste [carbon dioxide]," said Zapol, who is on the Institute of Medicine's Committee on Aerospace Medicine and the Medicine of Extreme Environments.

Theoretically, cutting metabolism would reduce the need for consumables and produce less waste, enabling spacecraft to travel lighter and faster.

"Wouldn't it be nice to arrest metabolism safely for long periods of time and reverse it when you wanted to?" Zapol said.

Before any spaceflyers benefit from hydrogen sulfide research, Zapol thinks severely injured people will.

"If someone loses a lot of blood, we might be able to safely reduce their need for oxygen," he said. "That would feasibly extend limited windows to perform life-saving operations."

Much to learn

For now, however, Zapol says an incredible amount of research remains before any work on humans can start.

"The next thing we need to do is scale this up to animals bigger than a mouse," he said, explaining that larger creatures can react very differently to experiments.

People, for example, have reported headaches and nausea from doses of hydrogen sulfide gas 2,700 times less concentrated than those used in the team's experiments. Ten weeks of continuous exposure to the same levels Zapol and others used has been shown to cause nose lesions, or ulcers, in mice.

But Zapol thinks that hydrogen sulfide may not be the key ingredient for inducing a suspended animation-like state in mice — a less-toxic compound may form after the gas is inhaled. If so, the toxicity of hydrogen sulfide could be circumvented.

"Chemistry of the blood is very complex," Zapol said. "We need to find out what, exactly, is circulating in the blood and causing what we've observed."

The National Institute of Health and Linde Gas Therapeutics in Lidingo, Sweden, funded the team's research.