Human Cadaver Brains May Provide New Stem Cells

Death will come for us all one day, but life will not fade from our bodies all at once. After our lungs stop breathing, our hearts stop beating, our minds stop racing, our bodies cool, and long after our vital signs cease, little pockets of cells can live for days, even weeks. Now scientists have harvested such cells from the scalps and brain linings of human corpses and reprogrammed them into stem cells.

In other words, dead people can yield living cells that can be converted into any cell or tissue in the body.

As such, this work could help lead to novel stem cell therapies and shed light on a variety of mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, autism and bipolar disorder, which may stem from problems with development, researchers say.

Making stem cells

Mature cells can be made or induced to become immature cells, known as pluripotent stem cells, which have the ability to become any tissue in the body and potentially can replace cells destroyed by disease or injury. This discovery was honored last week with the Nobel Prize.

Past research showed this same process could be carried out with so-called fibroblasts taken from the skin of human cadavers. Fibroblasts are the most common cells of connective tissue in animals, and they synthesize the extracellular matrix, the complex scaffolding between cells. [Science of Death: 10 Tales from the Crypt]

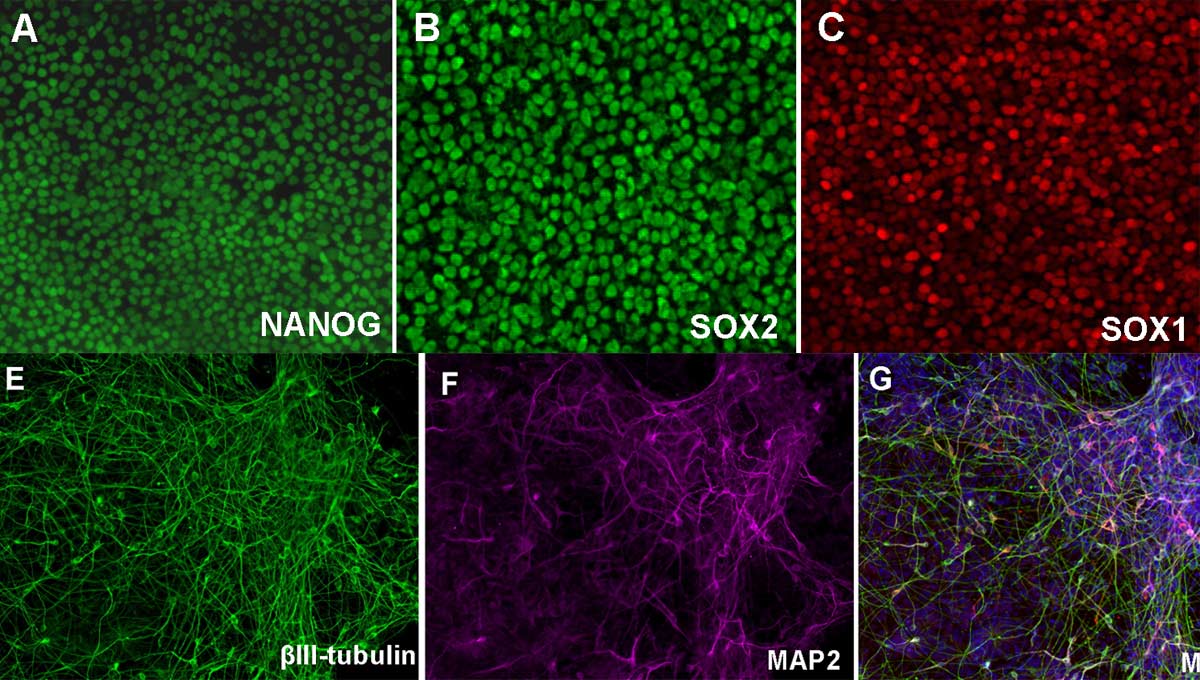

Cadaver-collected fibroblasts can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells using chemicals known as growth factors that are linked with stem cell activity. Reprogrammed cells could then develop into a multitude of cell types, including the neurons found in the brain and spinal cord. However, bacteria and fungi on the skin can wreak havoc on the culturing processes used to grow cells in labs, making the process tricky to successfully carry out.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now scientists have taken fibroblasts from the scalps and the brain linings of 146 human brain donors and grown induced pluripotent stem cells from them as well.

"We were able to culture living cells from deceased individuals on a larger scale than ever done before," researcher Thomas Hyde, a neuroscientist, neurologist and chief operating officer at the Lieber Institute for Brain Development in Baltimore, told LiveScience. Previous studies had only grown fibroblasts from a total of about a half-dozen cadavers.

The bodies had been dead up to nearly two days before scientists collected tissues from them. The corpses had been kept cool in the morgue, but not frozen.

The researchers found fibroblasts taken from the brain lining, or dura mater, were 16 times more likely to grow successfully than those from the scalp. This was expected, since the scalp is prone to fungal and bacterial contamination just like any other part of the skin. These contaminants can ruin any attempt to grow fibroblasts in lab dishes.

Surprisingly, scalp cells did proliferate more and grew more rapidly than dura mater cells. "This makes sense — the skin is constantly renewing, while the turnover in dura mater is much slower," Hyde said.

Future therapies

Cells from corpses might play a key role in developing future stem cell therapies. Successfully reprogramming induced pluripotent stem cells so they behave like the cells they are meant to replace means that samples of the mimicked cells must be present for comparison. Cadavers can provide brain, heart and other tissues for study that researchers cannot safely obtain from living people.

"For instance, we can compare neurons derived from fibroblasts with actual neurons from the same individual," Hyde said. "It tells us about how reliable a given method for deriving neurons from fibroblasts is. That can be crucial if, for example, you want to create dopamine-making neurons to treat someone with Parkinson's disease."

Studying how induced pluripotent stem cells develop into various tissues could also shed light on disorders that are due to malfunctions in development.

"We're very interested in major neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disease, autism and mental retardation," Hyde said. "By understanding what goes wrong with the brain cells in these individuals, we could perhaps help fix that."

The scientists detailed their findings online Sept. 27 in the journal PLoS ONE.