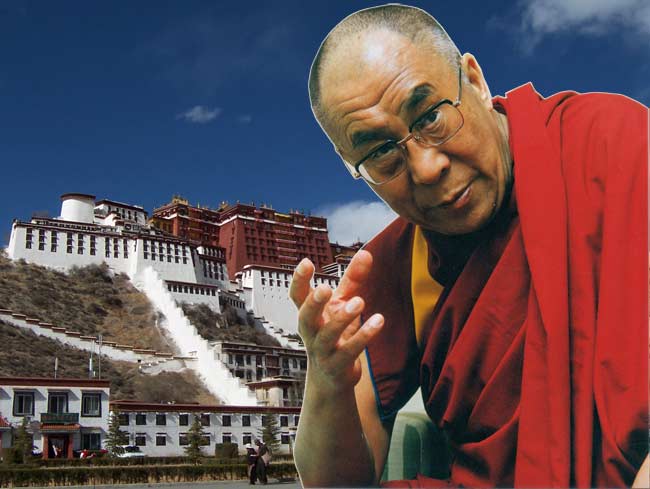

How the Dalai Lama Keeps His Cool

Many wonder how the Dalai Lama can retain his kindness and magnanimity, even as his homeland is torn apart by violence. New neuroscience research may help explain the exiled Tibetan leader's unremitting compassion for all people.

Meditation may increase a person's ability to feel empathy and benevolence for others, according to a study published March 26 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Scientists asked subjects — both expert meditators and novices — to practice compassion meditation while inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine (fMRI). The participants heard sounds designed to provoke an empathetic response, such as a distressed woman calling out, as well as positive sounds (a baby laughing) and neutral sounds (background noise at a restaurant).

"We wanted to see how compassion meditation changes the way you perceive emotional sounds," said Antoine Lutz, a neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin who conducted the research with his colleague Richard Davidson.

When subjects heard the sounds, both groups experienced more brain activity in areas associated with empathy and emotions while meditating than while not meditating. The distressed sounds elicited stronger empathetic responses than the positive and neutral noises, and the brain activity in these regions was much stronger in the seasoned meditators.

"The difference was very clear," Lutz told LiveScience. "We saw significantly more activation in this circuitry in experts than in novices. What is interesting is that the regions that are more activated are the regions which we think should be more important in compassion."

These regions include the insula, or insular cortex, which is associated with bodily representations of emotions, and the temporoparietal junction, which previous research has shown to be involved in distinguishing between oneself and others, as well as in perceiving the mental and emotional states of others.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Both of these areas have been linked to emotion sharing and empathy," Davidson said. "The combination of these two effects, which was much more noticeable in the expert meditators as opposed to the novices, was very powerful."

Sixteen of the 32 total subjects had practiced meditation for at least 10,000 hours; the same-aged beginners had learned the basics a week before the study began.

Compassion meditation involves first focusing on loved ones and directing loving-kindness toward them, and then extending that goodwill to all beings indiscriminately. This technique is widely practiced among Tibetan Buddhists, Lutz said.

The researchers argue that their findings suggest compassion can be learned and increased with practice, similar to any skill or talent.

"It kind of primes the mind to react with benevolence to others when a situation requires that," Lutz told LiveScience. "You naturally know how to feel compassionate about someone you care about. This practice tries to build on that and extend that to others."

Previous research has shown that meditation can increase mental focus and concentration and help people release negative emotions. Other claims on behalf of meditation, such as that it benefits health, have so far been unsubstantiated with research.

The researchers want to further test how much the boost in compassion persists once a person is not in a meditative state.

"These practices should change the emotional baseline of a person," Lutz said. "How does this change the way in regular life this person is behaving? That's the long-term question."

He and Davidson suggest that compassion meditation may benefit depressed people or young people who struggle with aggression and violence.

"I think this can be one of the tools we use to teach emotional regulation to kids who are at an age where they're vulnerable to going seriously off track," Davidson said.

More research is needed before meditation could be developed into a treatment, Lutz said.

"This study is really a first step," he said. "The next step is to try to longitudinally assess the effects of these techniques on behaviors and brain functions, and see how these techniques can eventually be applied to targeted populations."

- Video: Here's to Your Brain

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

- Using the Mind to Cure the Body