Meningitis Outbreak: Should Anti-Fungal Meds Be Given to Those at Risk?

An outbreak of deadly fungal meningitis linked to steroid injections has raised the question of whether people who received the shots, but don't have meningitis symptoms, should take anti-fungal drugs to prevent disease.

For now, health officials are not recommending use of the drugs as a preventative treatment, but that advice could change as officials learn more about the outbreak, experts say.

So far, 257 people have been diagnosed with meningitis after receiving contaminated steroid injections in the spine as a treatment for back pain, and of these, 20 have died. More cases are expected as the outbreak continues to unfold.

But around 14,000 people may have been exposed to the fungus through contaminated shots. Most of these people have been contacted by health officials to notify them of their potential risk for infection, and the Food and Drug Administration has warned about being vigilant for symptoms. The hope is that the disease can be diagnosed early so treatment can begin as soon as possible, said Curtis Allen, a spokesman for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients who develop meningitis are being treated with the anti-fungal drug voriconazole.

Whenever doctors prescribe a drug, they must consider the benefits of the medication against its risks. And currently, doctors don't know whether the drug — aimed at treating existing fungal infections — could also prevent the disease.

"The possible benefits are immeasurable," Allen said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While anti-fungal medications are used to prevent fungal diseases in some cases, such as with cancer and transplant patients, they have not been used to before to prevent this particular form of meningitis, said Dr. Peter Pappas, a fungal disease expert who is advising the CDC in the current outbreak.

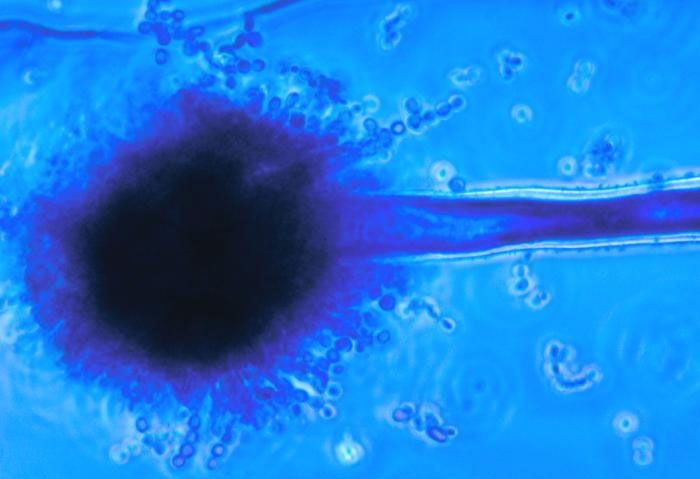

The vast majority of meningitis cases in the outbreak have been caused by the fungus Exserohilum — a fungus never before linked with meningitis. So doctors don't know how long patients would need to stay on the medications to sufficiently ward off a potential infection, Pappas said.

In addition, anti-fungal medications have dangerous side effects, including hallucinations, kidney damage and hepatitis. Most people on the drugs experience some side effects, the mildest of which is nausea, Pappas said.

"The medication used to treat this is pretty tough on people," Pappas said. "If this were penicillin or something that could be administered for a few doses over the course of a few days…perhaps that would make better sense," he said.

While a particularly concerned patient could, in theory, get a doctor to prescribe this medication to prevent fungal meningitis, "we do not think that a wise approach," Pappas said.

However, if officials are able to identify factors that put people at high risk for the disease, such as information about who received doses that were heavily contaminated, that might change the recommendation, at least for some people.

"If they could identify lots of this where a large percentage of patients are getting actual infections, you could make a case," for giving the drugs as a prevention measure, Pappas said.

Another reason the CDC might decide to change its recommendation is if it turns out doctors are not able to diagnose the condition early, said Dr. Thomas Patterson, chief of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, who is also advising the CDC.

But, fortunately, it appears so far that doctors have been able to make early diagnoses, Patterson said.

For now, the low percentage of cases (about 2 percent of exposed people), and the low mortality rate from the disease (about 8 percent), suggest that the current recommendations are working, Pappas said.

Pass it on: Health officials are not recommending anti-fungal medication as a preventative treatment in the meningitis outbreak, but that could change as more is learned.

Follow Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner, or MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

2nd measles death reported in US outbreak was in New Mexico adult

CDC data reveal plummeting rate of cervical precancers in young US women — down by 80%