Rogue Dumping of Iron into Ocean Stirs Controversy

A controversial experiment in which more than 200,000 pounds of iron sulfate were dumped into the Pacific Ocean west of Canada has scientists calling for more transparency in geoengineering.

Geoengineering is any deliberate and large-scale manipulation of environmental processes in order to impact Earth's climate. Some geoengineering projects, like the recent one, can have other impacts like boosting fish populations.

The project was conducted by a local group, the Haida Salmon Restoration Corporation, under the scientific advice of American businessman Russ George, formerly the CEO of a company called Planktos, Inc. The goal, according to Haida Salmon Restoration Corporation, was to trigger plankton blooms to restore salmon and other fish populations. Phytoplankton, teensy floating plants at the base of the ocean food chain, need iron to grow.

Similar ocean-fertilization schemes have been proposed as a way to lessen climate change, as phytoplankton take up carbon dioxide on the ocean's surface and sink to the bottom, removing carbon from the atmosphere.

This geoengineered approach to solving climate change is controversial, but even researchers who think it has promise said the Canadian experiment went about it the wrong way.

"It should have been done by a group of neutral scientists," said Victor Smetacek, a researcher at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany who conducted a small-scale ocean-fertilization experiment in 2009. Smetacek added, "The thing is, it's going to give iron fertilization a bad name."

Fertilizing the ocean

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Haida Salmon Restoration Corporation allegedly spread 220,462 pounds (100 tonnes) of iron sulfate in the Pacific 200 nautical miles west of the Haida Gwaii islands in July. The story was first reported by The Guardian newspaper. On Tuesday (Oct. 16), John Disney, the CEO of Haida Salmon, told CBC Radio's As It Happens that the Canadian government knew of the project beforehand.

Canada's Environmental Minister Peter Kent has denied the project was approved.

The controversy is likely to grow, as the project may have broken two international moratoria on ocean fertilization, the United Nations' convention on biological diversity and the London convention, which found large-scale experiments in ocean fertilization unjustified. [10 Climate Myths Busted]

George has attempted ocean-fertilization projects before, most notably in 2007, when his plan to dump iron near the Galapagos Islands drew fire from researchers and helped trigger the United Nations moratoria against such experiments.

George did not respond directly to queries from LiveScience, but said that the corporation will hold a news conference tomorrow (Oct. 19) to discuss the project.

"Our world class legal team which studied the legal position before the project and provided the formal legal opinion that this was legal will lead [the press conference]," George wrote in an email to LiveScience. He told The Guardian that a team of scientists are monitoring the experiment and called the U.N. rules against such projects a "mythology."

Breaking the rules

Whether George and the Haida Salmon Restoration Corporation will face legal troubles in the aftermath of the iron dump remains to be seen, but the international rules against such projects are mostly toothless, said Jason Blackstock, a physicist and policy adviser at the Oxford Institute for Science, Innovation and Society.

"There is naming and shaming, there is international pressure that can be brought to bear," Blackstock told LiveScience. There are not, however, fines or other punishments, he said.

Blackstock said the project in Canada was "the antithesis of how things should be done."

"There should not be an experiment that goes ahead and the public finds out about it afterwards," he said.

Research funding organizations could lead the drive toward better regulation of geoengineering experiments, Blackstock said. Rather than individual groups setting their own, possibly contradictory, rules, he said, funding councils should work together to develop guidelines for good geoengineering projects.

"The lack of transparency in this case is unacceptable, and that should be the primary focus of research funders and regulators," Blackstock said.

Is geoengineering a good idea?

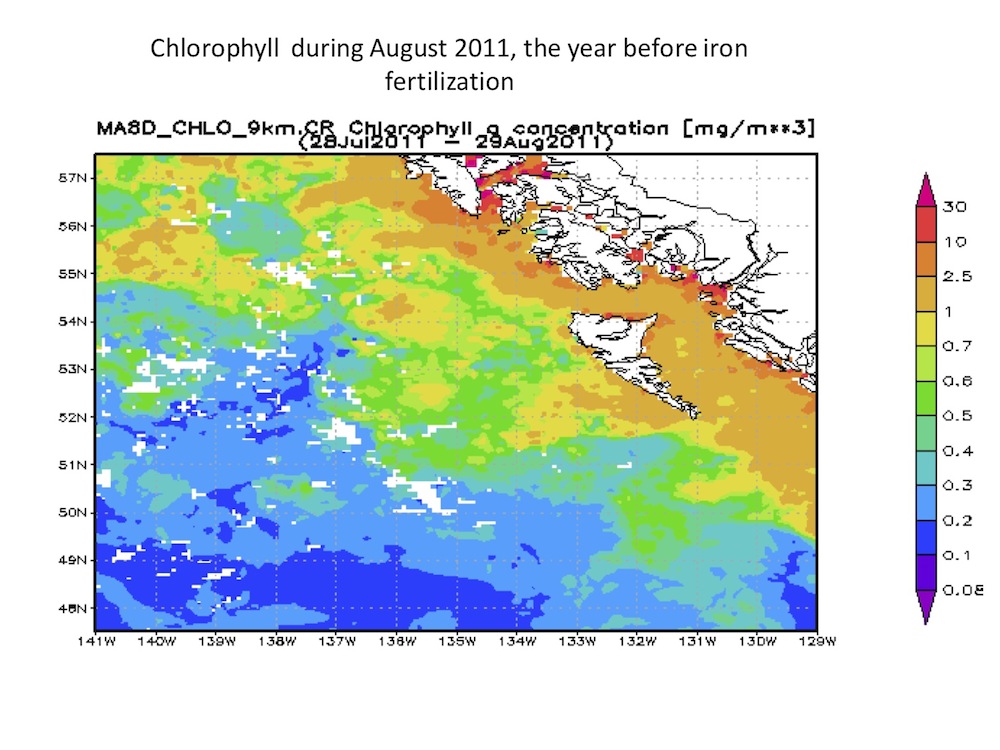

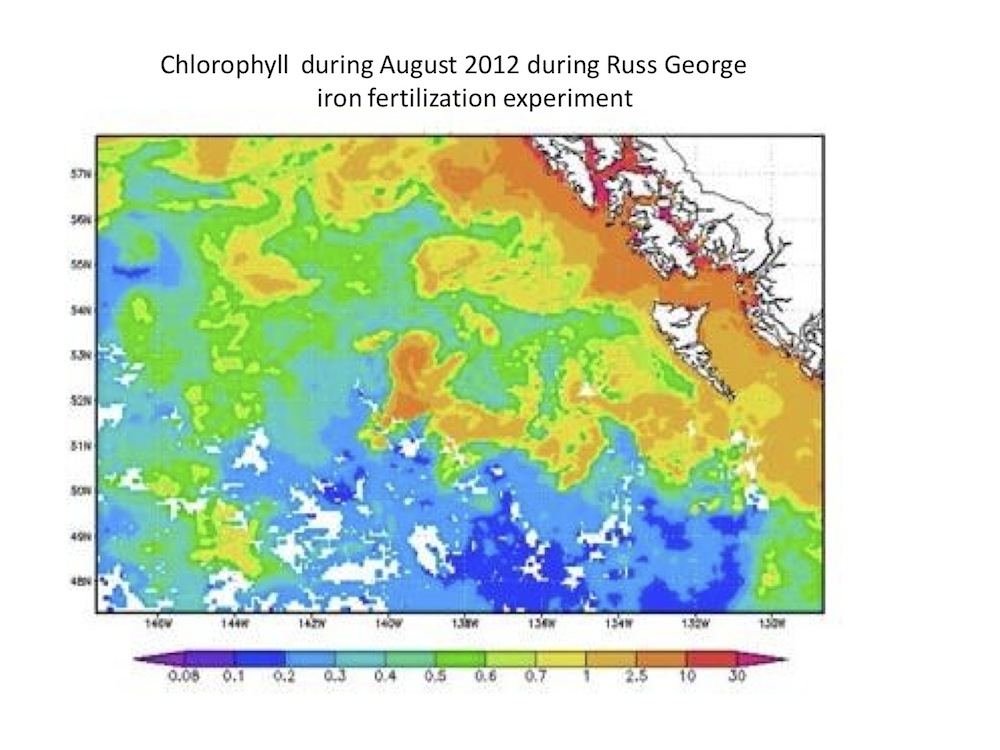

It's not yet clear what effect the Canadian iron dump had on the ecosystem, other than an enormous algae bloom visible from space — exactly what you'd expect to see after iron fertilization, Smetacek said.

Should ocean fertilization be used to combat climate change?

Whether that algae bloom had any carbon-capturing effect is also unknown. Smetacek and his colleagues recently published a study in the journal Nature finding that a small man-made algae bloom near Antarctica did successfully sequester carbon on the ocean floor. For every iron atom added to the site, the researchers estimate 13,000 carbon atoms sunk to the seafloor.

Even widespread fertilization of the oceans would result in about 0.5 to 1 gigaton of carbon being shuttled out of the atmosphere annually, Smetacek said. That's about a third to a quarter of the carbon added to the atmosphere each year from man-made and other sources. Many scientists would rather see humans stop producing carbon in the first place, a strategy known as mitigation.

"There's 18 reasons why it might be a bad idea; the solution to global warming is mitigation, it's not geoengineering," Alan Robock, a climate scientist at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., told LiveScience in 2010. "If anybody thinks this is a solution to global warming, it will take away what push there is now toward mitigation." [8 Ways Global Warming Is Changing the World]

But others, including Smetacek, think geoengineering may be the only option left to prevent catastrophic sea-level rise in a world where there is little political will to replace fossil fuels.

"I think we cannot avoid not trying to use it but we first need to do more experiments, we need to know more about how it functions, and the experiments have to be done very cautiously, they have to be done by scientists, by nonprofit people," Smetacek said. "We cannot afford to have the same greed which brought us to this impasse take over."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.