Oceans in 2100 May 'Sound' Like Dinosaur-Era Seas

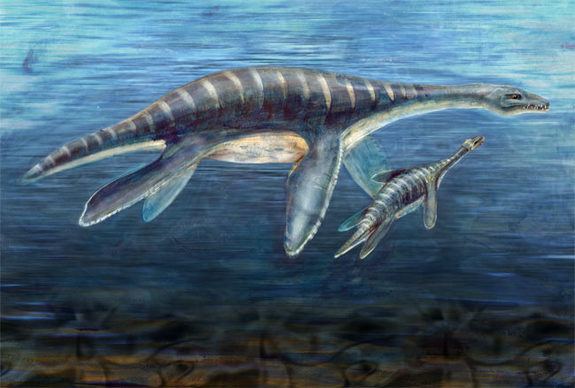

Scuba divers in the year 2100 might hear what the dinosaurs did, new research suggests.

Rising acidity in the oceans could set underwater acoustic conditions back to the Cretaceous period, scientists say, allowing some low-frequency sounds like whale songs to travel perhaps twice as far as they do now.

"We call it the Cretaceous acoustic effect, because ocean acidification forced by global warming appears to be leading us back to the similar ocean acoustic conditions as those that existed 110 million years ago, during the Age of Dinosaurs," David G. Browning, an acoustician at the University of Rhode Island, said in a statement.

Oceans tend to become more acidic when carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere rise. That's because a portion of that greenhouse gas enters the oceans, where it dissolves, and due to chemical reactions, makes the waters more acidic. Previous studies on seafloor sediments have allowed scientists to reconstruct ocean acidity for the past 300 million years, showing that there had been previous spikes and dips in acid levels.

But these sediments also allow scientists to reconstruct soundscapes.

The level of low-frequency sound absorption is, in part, dependent on pH levels (lower pH means more acidity), meaning this geological record can also be used to estimate sound transmission in the ocean during long-gone eras. (Lower pH levels mean lower sound absorption and better sound transmission.)

Browning and his colleagues predicted today's oceans have similar low-frequency sound transmission as they did about 300 million years ago, during the Paleozoic Era. But the oceans are becoming more and more acidic — faster than they have in the past 300 million years, according to recent estimates — putting underwater acoustic conditions on a fast track to the soundscape of 110 million years ago when seas were much more acidic.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This knowledge is important in many ways," Browning said in a statement. "It impacts the design and performance prediction of sonar systems. It affects estimation of low-frequency ambient noise levels in the ocean. And it's something we have to consider to improve our understanding of the sound environment of marine mammals and the effects of human activity on that environment."

His research suggests that by the next century, global warming will cause enough acidification to make low-frequency sounds near the ocean surface travel much farther than they currently do, possibly twice as far.

Browning will present his work at the upcoming meeting of the Acoustical Society of America in Kansas City, Mo.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.