Spaced Out: Majority of Gen X Can't Identify Home Galaxy

Identifying your home or street from a Google Earth image may be tough enough, but what about your cosmic address? Turns out, fewer than 50 percent of adults ages 37 to 40 know that humans live in the spiral Milky Way galaxy.

That's according to a new report of more than 4,000 American adults who make up the core of Generation X.

"Knowing your cosmic address is not a necessary job skill, but it is an important part of human knowledge about our universe and — to some extent — about ourselves," report author Jon D. Miller said in a statement.

Miller is the director of the Longitudinal Study of American Youth at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Beginning in 1986, with funding from the National Science Foundation, scientists have collected data about the lives and knowledge of Generation X.

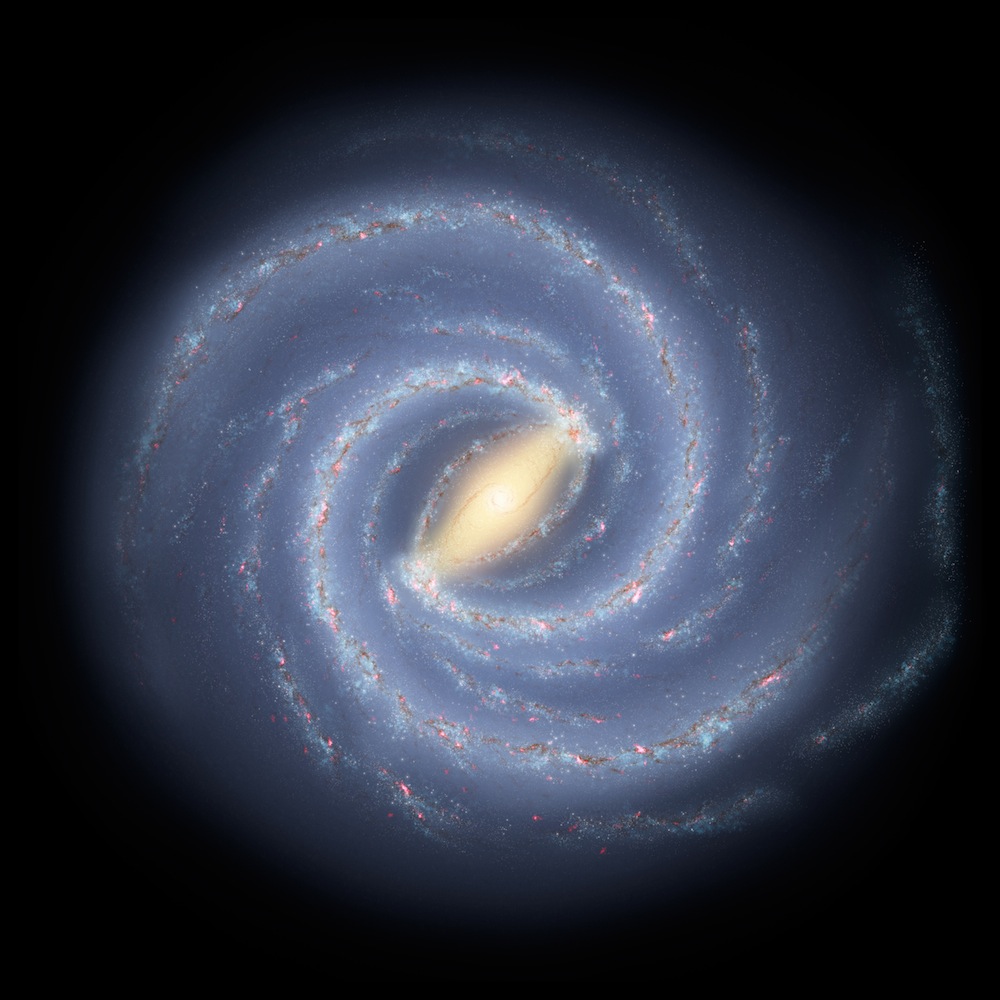

In the latest installment of the study, Miller showed participants a Hubble Space Telescope image of a spiral galaxy and asked them to identify the picture. The participants were asked to identify the image first in an open-ended question and then in a multiple-choice setup. [Infographic: Our Milky Way Galaxy]

Just 43 percent of participants gave an answer saying the image represented a galaxy like our own. And men had a leg up, with 53 percent of males and 32 percent of females nailing their cosmic location to some degree. Those with less than a high-school education fared the worst, with just 21 percent knowing our cosmic address, compared with 63 percent of those with doctorates or professional degrees who said the same.

"One of the factors that contributes to this educational difference is exposure to college-level science courses," Miller said. "The United States is unique in its requirement that all college students complete one year of college science courses as part of a general education requirement."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though four out of five participants indicated they had seen this type of space-telescope image before, often online, 60 percent said this was the first time they took a careful look at such an image.

Those who correctly identified the sparkly swirl as a spiral galaxy like the one we live in were more likely than the "cosmically lost" participants to agree with the statements:

- "When I see images like this, I am reminded of the vastness of the universe" (70 percent versus 53 percent);

- "Images like this show how small and fragile planet Earth is in the context of the universe" (58 percent versus 44 percent);

- "Seeing images like this make me want to learn more about the nature of the universe" (27 percent versus 19 percent);

- "It is very likely that there is intelligent life at many places in the universe" (39 percent versus 26 percent).

However, those in the know about the Milky Way were slightly less likely than the other participants to agree that "the size and complexity of the universe proves the greatness of God's creation" (45 percent versus 51 percent, respectively).

"Unlike our distant ancestors who thought the Earth was the center of the universe, we know that we live on a small planet in a heliosphere surrounding a moderate-sized star that is part of a spiral galaxy," Miller said. "There may be important advantages in the short-term — the next million years or so — to knowing where we are and something about our cosmic neighborhood."

With the rise of the Internet, Miller noted, such images and cosmic information are more accessible than ever. Even so, he said, "some of the science information on the Internet is incorrect or misleading." When asked, participants indicated the most trusted Internet resources for universe-related information included a NASA website, a program or exhibit at a planetarium or museum, a PBS Nova science show, a Discovery Channel science show and a lecture by an astronomy professor. The least trusted sources: a lecture by a leader of a church or religious group.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.