'Genius' Award Winner Hunts Down Dead Zones

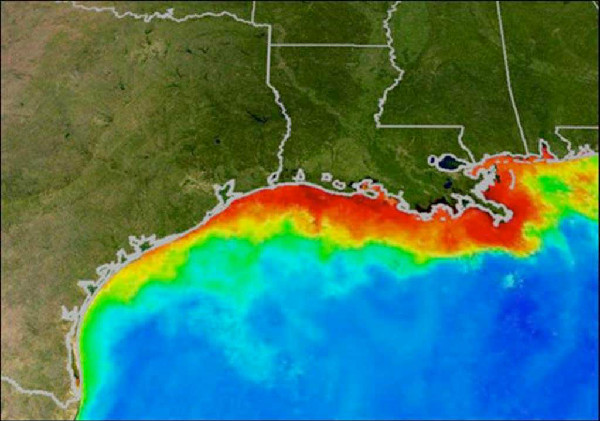

In recent summers, the so-called "dead zone" in the Gulf of Mexico has been as large as the state of New Jersey. Marine ecologist Nancy Rabalais has been working for nearly 30 years to track the zone's size and location, to determine what causes it and to try to prevent it from continuing to grow.

Her work has paid off; out of the blue, she recently received a phone call to tell her that she'd been awarded a $500,000 MacArthur Fellowship, also known as the "genius" grant, which can be spent however she likes.

Rabalais, a researcher at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium in Cocodrie, said she plans to spend it on her research, which has linked dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico to nutrient runoff from fertilizers used in farming throughout the Mississippi River basin. These nutrients spawn enormousblooms of algae, which eventually sink and decay, consuming oxygen in the water column. This creates vast tracts of water without oxygen, killing almost all life in the immediate area.

OurAmazingPlanet chatted with Rabalais about her work and receiving the award. The following is an edited transcript of the conversation.

OurAmazingPlanet: Tell me about the experience of getting the award.

Nancy Rabalais: Well, I'm certainly honored. I never thought I'd have one.

OAP: How'd you find out that you'd won?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

N.R.: I was in Mexico at a meeting and I got a phone call from a number I didn't recognize. And I thought, should I answer it? I did, and the gentleman informed me I'd won the award. It was a surprise.

OAP: What do you plan on using the award money for?

N.R.: Putting it back into our research. Our budget is shrinking due to budget problems. It will help me pay my students, pay for equipment and traveling.

OAP: Tell me about your research.

N.R.: We clearly linked hypoxic areas, or dead zones, in the Gulf to landscape activities in the Mississippi watershed. Those connections are pretty obvious in other areas around the world. It was hard to convince water managers and resource managers that this was the situation here.

It's led to legislation and policy statements and efforts to do something about it. That's pretty rewarding, even though [these policy efforts] haven't gone that far.

OAP: What do you mean by "landscape activities?"

N.R.: Mostly farming — most excess nitrogen and phosphorous comes from farming activities.

OAP: What's so bad about dead zones?

N.R.: When you consider that an area the size of New Jersey doesn't support fish, shrimp, crabs or any other marine life, that's significant. The fisheries in the Gulf haven't cratered, but they have in other parts of the world with dead zones.

OAP: What can be done to fight these dead zones?

N.R.: It's going to take changes in the way we live, and in our agricultural system; we'll have to address agricultural subsidies, which encourage overfertilizing. But it's not just the farm community; wastewater plants can get better. There's also atmospheric deposition of nutrients into the water from burning fossil fuels.

There are a lot of best management practices for farming that can be implemented … There's no mechanical or chemical solution.

OAP: How'd you get interested in this topic?

N.R.: The director [of the marine consortium] suspected it was a problem, and got the money to study it, and said: "Research this." So I did. That was 28 years ago.

The more I studied it, the more interested I became. The public outreach became important, as well.

It's a problem of water quality, which affects the health of everybody. It affects farmers. It affects fishermen.

OAP: What are you working on now that you're most excited about?

N.R.: We have instruments offshore that monitor oxygen in real time, and I'd like to see more about how these oxygen levels change as dead zones grow.

OAP: Is it difficult to get people to think about changing their behavior when it's a matter of collective responsibility, as opposed to, say, the issue of pollution coming from a single factory?

N.R.: It is. Also it's difficult to think about something happening a thousand miles away. It's difficult to make changes. There are a lot of good-intentioned, more locally oriented farmers, not those in big agribusiness, that are doing the right thing. They are working with sustainable crops and artificial wetlands [that take up the nutrients that would otherwise go into the dead zone].

It's more economical for them to do some of these conservation activities than to keep buying fertilizer that just runs off the land. Farmers have always cared, because their land is their livelihood.

OAP: Why should other people care about dead zones?

N.R.: They should be concerned because the [dead zones] are affecting the livelihood and health of others.

OAP: What have been some challenging moments in the course of your work?

N.R.: Once in 2010, I accidentally came up from one of our dives under a [plume] of oil from the Deepwater Horizon. That was quite unpleasant. We got me and my buddy out of the water as soon as possible. I got oil all over me, and on my hair. But nobody got sick or anything.

Our marine lab has also been hit repeatedly by hurricanes like Hurricane Katrina. The storms seem more frequent than before. And the water level is getting higher with each storm.

OAP: How'd you first get interested in studying the ocean?

N.R.: My biology teacher in 8th grade turned me on to biology, and I took courses in that in undergrad. My school had a lot of marine-oriented trips; I learned to scuba dive, and it went from there.

OAP: What are you focused on studying now and in the near future?

N.R.: I have one large grant to study marsh health and ecosystem recovery. I'm continuing with the hypoxia work, and I'm never going to give up.

Reach Douglas Main at dmain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @Douglas_Main. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.