How a Bubblegum Coral Conquered the Globe

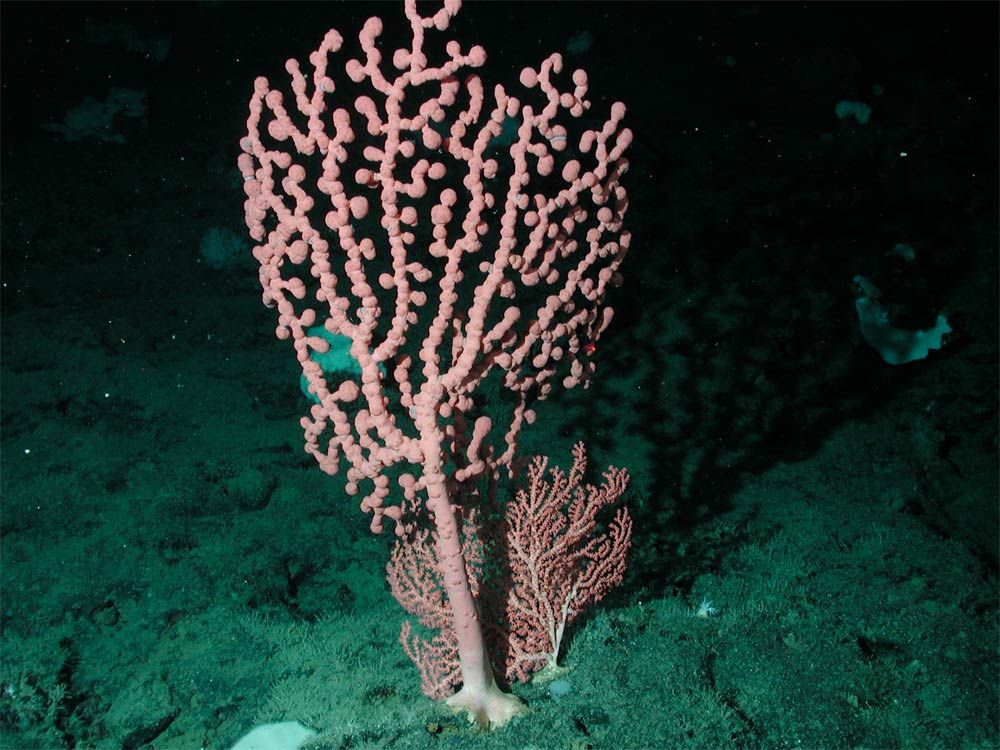

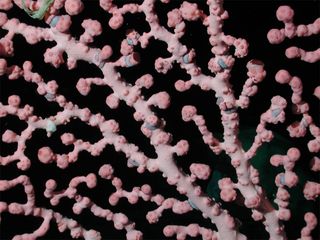

For a resident of the deep sea, a species of bubblegum coral is unusually cosmopolitan. These corals build often-colorful, knobby-armed structures deep in the oceans, where they appear comfortable nearly everywhere outside of the tropics.

A new genetic study not only indicates these widespread populations belong to a single species, but it also offers a glimpse at how this single species of bubblegum coral, Paragorgia arborea, spread around world. The researchers' reconstruction suggests the coral's ancient migration started in the North Pacific more than 10 million years ago, from which the colony-building animals may have hitched a ride on ancient ocean currents to travel to new seafloor habitat.

One species or many?

There are multiple types of bubblegum coral, but this particular species piqued the interest of researchers when they saw it was unusually widespread for a deep-sea organism. Paragorgia arborea has been found in the northern and southern Pacific and Atlantic, the Indian, the Arctic and the Southern oceans. [See Photos of Bubblegum Coral]

"It was really puzzling, there was this deep-sea species that could be found all over the world, except in the tropics," said Santiago Herrera, one of the researchers and a doctoral candidate with the MIT-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) Joint Program in Oceanography. "It makes you doubt it was a single species."

This bubblegum coral forms colonies on the ocean floor to depthsas great as 4,921 feet (1,500 meters). The structures appear in hues from bright red, orangish pink and pale pink to white in photographs taken using artificial light.

On the seafloor, the coral's branches create habitat for other creatures, much like trees in a rain forest do. But unlike trees, bubblegum coral eats tiny dead organisms raining down from above, and sometimes traps its own prey.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These feeding habits also distinguish it from coral that forms reefs in shallower, tropical waters, which team up with photosynthetic algae.

Clues in DNA

Herrera and his colleagues analyzed the genetic code from 130 pieces of this bubblegum coral contained in laboratory and museum collections; the oldest came from the Smithsonian Institution's collection, which was pulled from the seafloor off of North Carolina in 1878.

The researchers focused on regions of corals DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) found in the cells'mitochondria, the energy-producing centers and from the corals' nucleus, the cells' command center.Several analyses they conducted indicated these samples most likely all shared a common ancestor, one their close relatives did not, making them members of a single species.

Finding a widespread organism like this, then providing strong evidence its populations all belong to one species is a significant achievement, said Stephen Cairns, curator of corals at the Smithsonian Institution's National Natural History Museum.

Ancient migrations

Herrera, and colleagues Timothy Shank, an associate scientist at WHOI and Juan Sanchez, an associate professor at the Universidad de los Andes in Colombia, found the genetic composition of the coral samples varied depending on where they thrived, such as the North Atlantic or the South Pacific.

To see how this came to be, they looked back in time. The age of a fossil from a related coral provided the upper limit on their timeline, and to get an idea of the ages for the P. arborea populations, the researchers compared the relative abundance of genetic differences among them. [Image Gallery: Colorful Coral]

Their results indicated this species of bubblegum coral appears to have originated in the northern Pacific, possibly in the west, more than 10 million years ago, then traveled south into the southern Pacific. After millions of years, the coral reached the Atlantic, by either traveling around the tip of South America or through the Central American Seaway, before the Isthmus of Panama blocked the two oceans and the tropical ocean warmed too much for the corals.

Although their colonies are attached to the seafloor, corals broadcast their eggs and sperm into the water. Ocean currents could have carried these, the corals' larvae and the young polyps the larvae become.

"You can go from Alaska down to Chile along the coast of the Americas if you have the right currents,"Cairns said. "Time has a way of allowing unusual things to happen."

In fact, the team points out, the models of currents at the time during the Miocene Epoch show deep waters in the western Pacific moving south. The eastward flow of the Antarctic circumpolar current was already in place. Meanwhile, in the Atlantic, the current's southward flow of deep water had yet to develop, making the corals' spread into the northern Atlantic plausible.

The study was published today (Oct. 23) in the journal Molecular Ecology.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.