Carthage: Ancient Phoenician City-State

Founded by a seafaring people known as the Phoenicians, the ancient city of Carthage, located in modern-day Tunis in Tunisia, was a major center of trade and influence in the western Mediterranean. The city fought a series of wars against Rome that would ultimately lead to its destruction.

The Phoenicians were originally based in a series of city-states that extended from southeast Turkey to modern-day Israel. They were great seafarers with a taste for exploration. Accounts survive of its navigators reaching places as far afield as Northern Europe and West Africa. They founded settlements throughout the Mediterranean during the first millennium B.C.

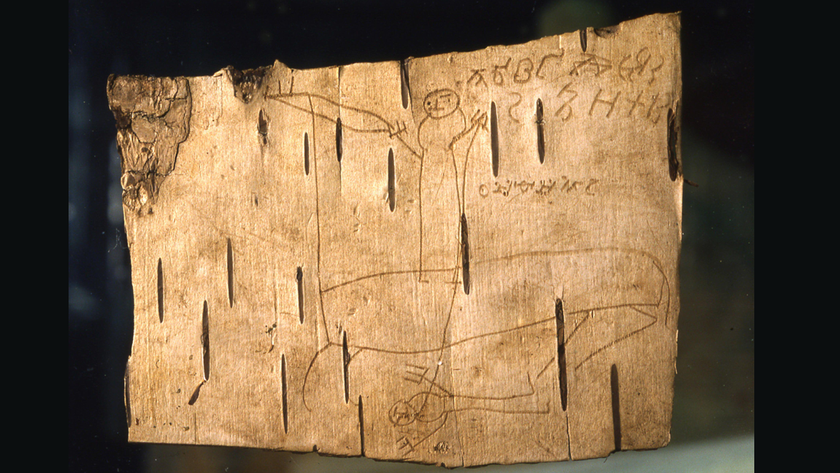

Carthage, whose Phoenician name was Qart Hadasht (new city), was one of those new settlements. It sat astride trade routes going east to west, across the Mediterranean, and north to south, between Europe and Africa. The people spoke Punic, a form of the Phoenician language.

The two main deities at Carthage were Baal Hammon and his consort, Tanit. Richard Miles writes in his book Carthage Must Be Destroyed (Penguin Group, 2010) that the word Baal means “Lord” or “Master,” and Hammon may come from a Phoenician word meaning “hot” or “burning being.” Miles notes that Baal Hammon is often depicted with a crescent moon, while Tanit, his consort, is shown with outstretched arms.

The city

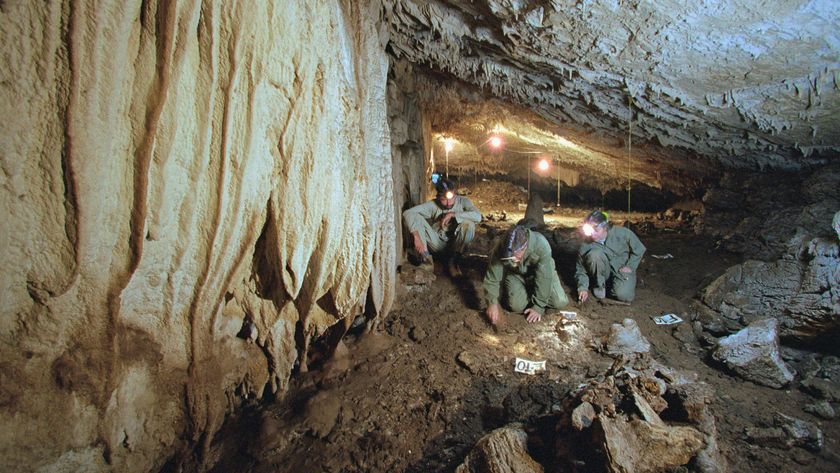

The earliest archaeological evidence of occupation at Carthage dates to about 760 B.C. The settlement quickly grew to encompass a 25-30 hectare (61-74 acres) residential area surrounded by a necropolis (graveyard), notes Roald Docter, of Ghent University.

Within a century the settlement would have city walls, harbor installations and a “Tophet,” a controversial installationin the southeast of the city that may have been used for child sacrifice (it could simply have been a special burial ground).

A great marketplace (which the Greeks called an “agora”) also developed and, in later centuries, was located by the sea, writes University of Sydney professor Dexter Hoyos in his book, The Carthaginians (Routledge, 2010). “Besides its role as a market, it would be the obvious place for magistrates to assemble the citizens for elections and lawmaking,” he writes.

By 500 B.C., the city’s system of government, as suggested by the large marketplace, was a republic of sorts. Hoyos notes that the Carthaginians had two elected sufetes (the Greeks called them kings) that served along with a senate, citizen assembly and pentarchies (five-person commissions). There was also an enigmatic body called the “court of 104” that occasionally crucified defeated Carthaginian generals.

As with other ancient (and to some degree modern) republics, wealthy individuals from powerful families had the advantage in getting into office. Nevertheless, the combination of trade opportunities and republican structure appears to have had some success at Carthage. In the second century B.C., just before it was destroyed by Rome, the city boasted a population estimated at more than half a million people.

As the city grew, so did its external influence, with evidence of involvement in places such as Sardinia, Spain and Sicily, entanglements that would ultimately lead to conflict with Rome.

Legendary foundation

It wasn’t unusual for large cities in the ancient world to have elaborate foundation myths, and Greek and Roman writers had a tale for Carthage, one set more than 2,800 years ago.

According to legend, Carthage was founded by Elissa (sometimes referred to as Dido), a queen of the Phoenician city of Tyre, located in modern-day Lebanon. When her father died she and her brother Pygmalion both ascended the throne. This did not work out well, with Pygmalion eventually ordering the execution of Elissa’s husband, the priest Acherbas.

Elissa, along with a small group of settlers, would leave the city, sailing nearly 1,400 miles (2,300 km) west. The local king, a man named Iarbas, said they could build as large a settlement as could be encompassed by an ox-hide at Carthage (the settlers ended up slicing up the ox-hide really thin). Iarbas would eventually demand that Elissa marry him to which she responded by killing herself with a sword atop a funeral pyre.

Archaeologists have yet to find remains of Carthage datable to the ninth century B.C., and scholars tend to regard this story as being largely mythical. The tale, moreover, comes largely from Greek and Roman sources, and it’s debatable whether Carthaginians actually believed in it themselves.

Punic Wars

Rome and Carthage would fight a total of three "Punic Wars," which ultimately led to the latter’s destruction and re-founding.

The two cities were not always hostile. Before the First Punic War started in 264 B.C., they had a long history of trade, and at one point the two powers actually allied together against Pyrrhus, a king based in Epirus, which is in modern-day Albania. This is known today as the Pyrrhic War.

Historians still debate the causes of the Punic Wars but the spark that lit it off happened in Sicily. Carthage had long controlled territory on the western part of the island, fighting off the Greek city of Syracuse.

In 265 B.C., the Mamertines, a group of former mercenaries based in Messina, Sicily, appealed to both Carthage and Rome for help against Syracuse.

They ended up getting both requests answered.

Richard Miles writes that Carthage sent a small force to Messina, which was then ejected by a larger Roman force. The situation quickly escalated into open war between the two great powers.

In the beginning, Carthage had naval supremacy, giving them the edge. However, the Romans built up a fleet quickly, developing a bridge-like device called a “corvus,” which made it easier for their embarked troops to storm Carthaginian ships.

The First Punic War would go on for more than 20 years and end in Carthage accepting a humiliating peace treaty that ceded Sicily along with much of their Mediterranean holdings to Rome.

The Second Punic War would last from 218 to 201 B.C. and would see the Carthaginian general Hannibal, based in Spain, attack Italy directly by going through the Alps. At first his attack proved successful, taking a great deal of territory and inflicting a Roman defeat at the Battle of Cannae, in southern Italy in 216 B.C.

Hannibal was, however, was unable to take Rome itself. Over the next decade, a series of Roman counterattacks in Italy, Spain and Sicily turned the tide of war against Carthage and in 204 B.C., a Roman force led by Publius Cornelius Scipio landed in Africa, defeating Hannibal at the Battle of Zama. The peace imposed on Carthage left it bereft of land and money.

The Third Punic War, from 149 to 146 B.C., consisted mainly of a prolonged siege of Carthage, which ended with the city being burned. A modern-day myth has the Romans “salting the earth” to prevent the fields of Carthage being tilled again; however, there is no ancient evidence for this.

Roman Carthage

Carthage would not be gone for long. A century later, Julius Caesar founded a new Roman city on the site and by the second century A.D., it was the largest North African city west of Egypt.

Researcher Aïcha Ben Abed writes that among its features were giant “Antonine baths,” that were “the largest public baths in the Roman Empire” (from Tunisian Mosaics, 2006, Getty Publications), a sign of the city’s success.

The importance of Carthage would not diminish as time went on and today Tunis, a modern-day capital of more than 2 million people, surrounds the ancient ruins.

— Owen Jarus, LiveScience Contributor

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.