Death-Defying Trick: Cells Return From the Brink of Death

This Research in Action article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Apoptosis, sometimes called "cellular suicide," is a normal, programmed process of cellular self-destruction.

It helps shape our physical features and organs before birth, and it rids our bodies of unneeded or potentially harmful cells, including cancerous ones. But apoptosis also can kill too many cells after a heart attack or stroke, causing tissues to die. For these reasons, scientists want to better understand the process.

Cells come equipped with the instructions and instruments necessary for apoptosis. They keep these tools — proteins that are called proteases — carefully tucked away until a signal inside or outside the cell triggers the apoptosis.

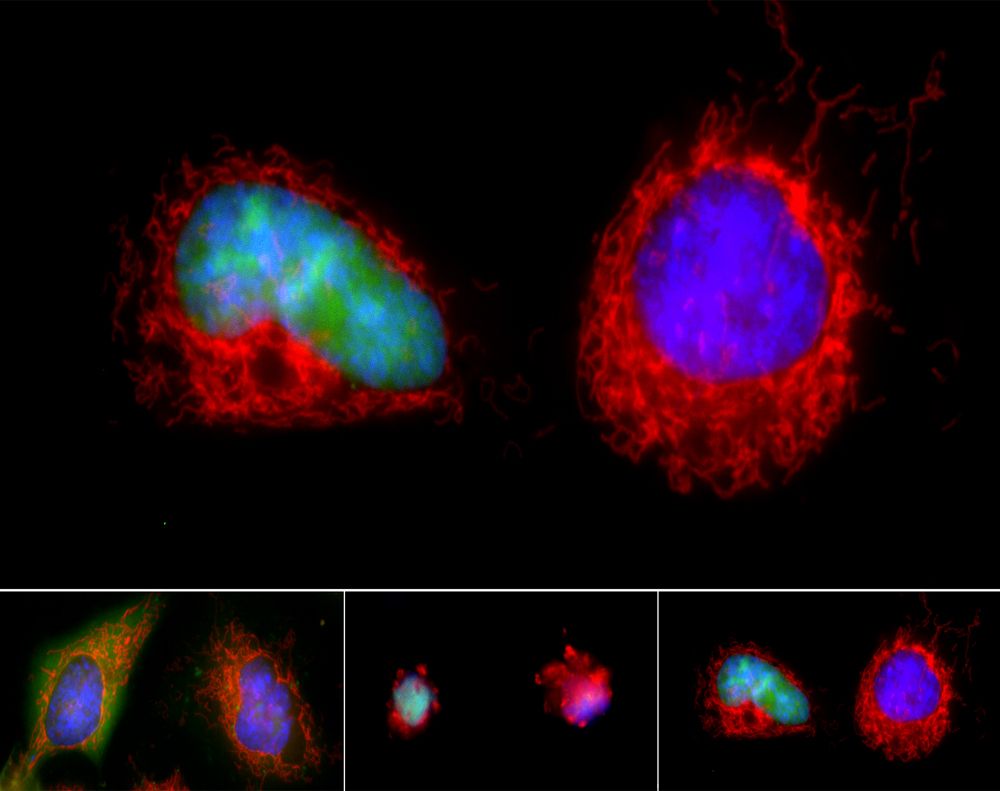

What does apoptosis look like? First, the cell shrinks and pulls away from its neighbors. Then the surface of the cell can bulge, with fragments breaking away. The DNA in the cell's nucleus condenses until the nucleus itself disintegrates, followed by the entire cell.

Do cells ever defy their fate? Yes, according to new research that shows many cell types on the brink of self-destruction can bounce back after their apoptotic trigger is removed.

Scientists at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine exposed healthy mouse liver cells to ethanol, a toxin that can induce cell death. Within hours, the cells showed signs of dying. But when the researchers washed away the ethanol, the shriveled cells plumped back up, smoothed out their membranes and regained normal organelles. The researchers observed this phenomenon in mouse brain and rat heart cells, and they called it anastasis — a Greek word for "rising to life."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The changes during anastasis went beyond physical appearance. Gene activity patterns also reversed from apoptotic to healthy ones, and DNA that had been chopped up during apoptosis got stitched back together. Occasionally, though, mistakes were made, leading a small percentage of cells to grow abnormally and develop some hallmarks of cancer.

Since anastasis could be harnessed to prevent or treat conditions where cell survival or excess cell death is harmful, the researchers are continuing their investigations into the mechanisms behind it.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. To see more images and videos of basic biomedical research in action, visit NIH's Biomedical Beat Cool Image Gallery.

Editor's Note: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Research in Action archive.