Flying Fish Evolved to Escape Prehistoric Predators

The first flying fish may have evolved to escape marine reptile predators, researchers say.

These new findings hint that marine life may have recovered more quickly than before thought after the greatest mass extinction in Earth's history, scientists added.

Modern flying fish are capable of gliding through the air as much as 1,300 feet (400 meters) in 30 seconds, with a maximum flight speed of up to about 45 mph (72 kph), probably flying mainly to escape from predators such as dolphins, squid and other fish. Modern flying fish live in tropical and subtropical waters, and no known fossil specimens are older than 65 million years.

Now researchers find evidence that flight evolved another time in the history of fish. This is the earliest example of gliding on water seen in vertebrates — that is, creatures with backbones. [Image Gallery: The Freakiest Fish]

Winged fish

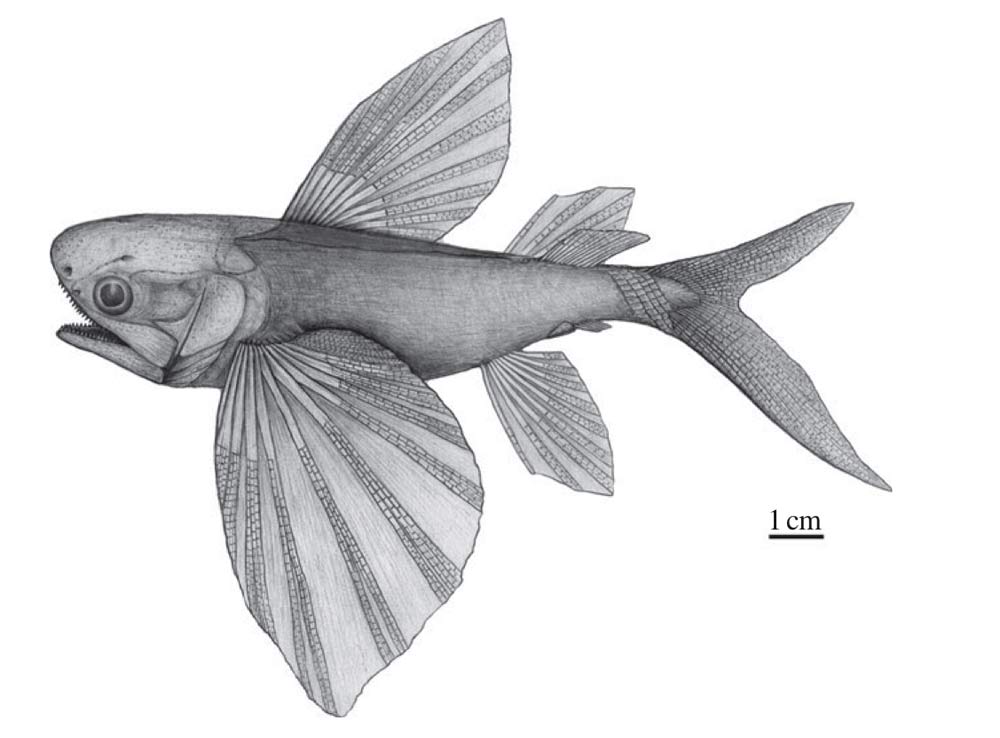

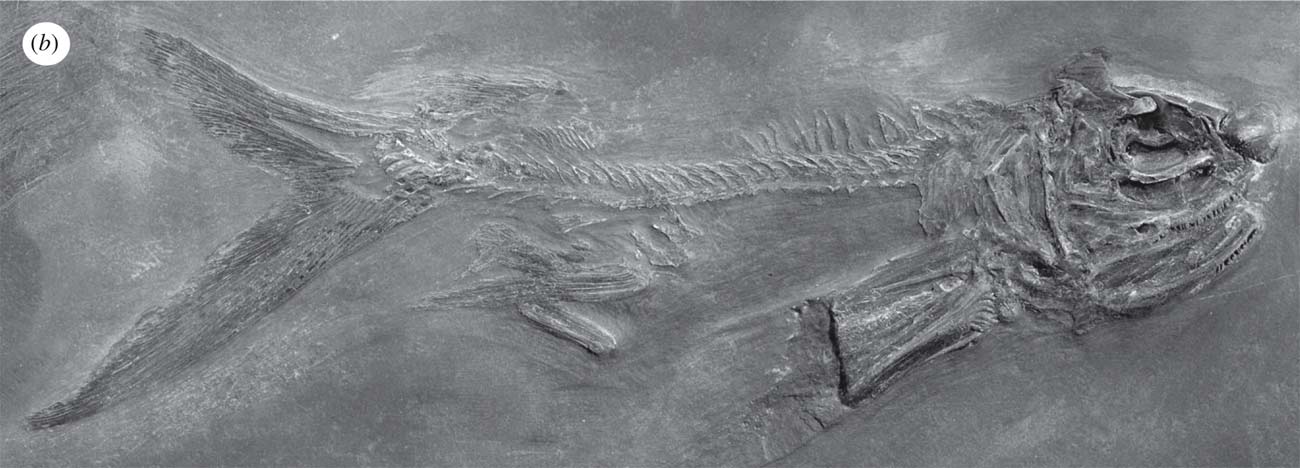

Scientists analyzed fossils they excavated from southwest China in 2009. The ancient bones come from a marine fish named Potanichthys xingyiensis. "Potanos" means winged and "ichthys" means fish in Greek, while "xingyiensis" refers to the city of Xingyi near where the fossil was found.

The fish lived about 235 million to 242 million years ago in what researchers call the Yangtze Sea. This was part of the eastern Paleotethys Ocean that sat about where the Indian Ocean and Southern Asia are now located.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The newfound fish was apparently capable of gliding just like modern flying fish. For instance, it had a greatly enlarged pair of pectoral fins that could have served as wings. It also had a deeply forked tail fin whose lower half was much stronger than its upper half, and swimming with such a fin could potentially generate the power needed to launch the fish out of water.

However, modern flying fish do not appear to descend from this fossil. Instead, the ability to glide on water seems to have evolved independently in this ancient lineage.

Other fossils unearthed in the same area as Potanichthys include those of marine reptiles such as dolphin-shaped ichthyosaurs. These ancient flying fish may have evolved gliding for much the same reasons as modern flying fish — to escape dangerous predators.

"The discovery of Potanichthys significantly adds to our knowledge of the ecological complexity in the Middle Triassic of the Paleotethys Ocean," said researcher Guang-Hui Xu, a paleontologist at China's Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing.

End-Permian extinction

The extinct group of fish to which this fossil belonged, known as the thoracopterids, was previously only seen in Austria and Italy. These findings suggest such fish lived from the western to eastern rim of the Paleotethys Ocean, hinting that other forms of life back then could have once spread from what is now Europe to Asia.

"In modern ecosystems, due to limitations of muscle function, flying fishes are unlikely capable of flight at temperatures below 20 degrees C (68 degrees F)," Xu told LiveScience. "We can reasonably apply similar limitations to the Triassic thoracopterids, and we suggest that Potanichthys adds a new datum supporting a generally hot climate in the Middle Triassic eastern Paleotethys Ocean."

Potanichthyslived about 10 million years after the end-Permian mass extinction about 250 million years ago, the greatest die-off in Earth's history, which claimed as much as 95 percent of the world's species.

"The end-Permian mass extinction was the most dramatic event to impact ecological systems on Earth, and recovery from this extinction has long been viewed as more prolonged than the recoveries following other mass extinctions," Xu said. "As the earliest evidence of over-water gliding in vertebrates, the new discovery lends support to the hypothesis that the recovery of marine ecosystems after the end-Permian was more rapid than previously thought."

The scientists detailed their findings online Oct. 31 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.